A Spiritual Case of Sand Fever

If you have spent any time in Case Library this week, you have undoubtedly noticed the persistent sound of metallic vibrations coming from the main study lounge on the third floor. Or maybe, like senior Maddie Buttitta, you noticed some colorfully clad strangers on the fifth floor:

“The monks were grabbing a bite to eat in the library café…perhaps muffins, or a frappuccino?” Buttitta cleverly quipped.

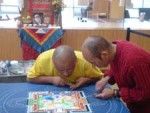

What Colgate students may not realize is that they are in fact witnessing the creation of a sacred, and only recently publicized, Tibetan art form known as a sand mandala. The sound vibrations you have heard is created by the rubbing together of small copper funnels, called chukpu. The friction caused by rubbing chukpu together in turn distributes vibrantly colored sand on a pre-prepared map of the mandala. Colgate’s two Tibetan monk visitors, dressed in traditional red and yellow robes, stand stooped over a small table for seven hours each day, stopping their work only briefly for tea — not frappuccinos.

The monks, brought to Colgate University courtesy of Professor of Physics and Astronomy Vic Mansfield’s class CORE 179: Tibet, are part of the Dalai Lama’s Namgyal monastery in Dharamsala, India. They represent the only formal branch of Tibetan Buddhism in the western world, located in Ithaca, New York. For over two thousand years, sand mandalas were kept behind closed doors, meant only for the eyes of monastic scholars and their spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama himself. But in 1988, the Dalai Lama allowed the first public construction of a sand mandala at the Museum of Natural History in New York City as a cultural offering, and as a means of preserving the fading Tibetan culture. Colgate students and faculty have the rare opportunity to participate in this ancient art form by viewing the construction of the mandala, talking with the monks and contributing to the dissolution process later in the week.

Though the presentation intends to spread understanding and awareness of Tibetan Buddhism, the Colgate student body’s reaction is mixed. While students in Mansfield’s CORE Tibet class, members of the Buddhist Students Association and Students for a Free Tibet appreciate the sacred and spiritual value of the presentation, other students unfortunately remain confused and irked by the distraction. Senior Mary Beth King, an art history major, values her quiet time in the library:

“I think it’s nice,” King said, “but I think that, like the display on drunk driving, there are probably places better suited for such things. There was nowhere in the library where you couldn’t hear the grating noise they were making, and it was really frustrating.”

Many other students are not aware of the greater significance of the project, though they appreciate the mandala’s aesthetic value.

“It was absolutely beautiful and so, so intricate,” Senior Dave Pletcher mused, who took Vic Mansfield’s CORE 179 class in 2004.

The students and faculty who organized the presentation have distributed posters and literature about Tibetan Buddhism and the sand mandala and though the monks carefully prepare the impressive display over the course of the week, it remains a temporary venture. Because mandalas are meant primarily for religious use, and not aesthetic or artistic value, they are never displayed for longer than it takes the monks to complete them.

The mandala in Case Library, which represents the palace of the Boddhisatva of Compassion, will be taken to Taylor Lake on Friday to be dissolved. For Tibetan Buddhists, this process indicates the transitory quality of existence and the release of compassion for all living beings. Thus, whether the persistent vibrations of the chupku draw you to the display, or you are truly interested in learning about the sacred value of the mandala from true Tibetan monks, this momentous event will only last until the end of the week, when it will literally dissolve without a trace.