A Murderous Desire for Fame

The dead are rarely given time to rest in America.

Within hours, politicians nearly invariably use the victims as footstools to harp or defend their cause. The first points a bony finger at weapons, and then the second clambers up to screech about mental health. The debate is the same nearly every time, most especially in that the only thing it conclusively generates is an enormous amount of noise. Hardly just from politicians either; each new incident creates a nationwide controversy for weeks as journalists meticulously document every aspect of the killer’s life and psychologists struggle to compose a complete mental profile. Consistently, the American public knows more about the life, motivation and mindset of a school shooter than they do of presidents, celebrities, athletes or philosophers.

We make these men into heroes.

On April 26, 1998, Eric Harris wrote in his journal, “I want to leave a lasting impression on the world.” This is a fairly common sentiment. Most people, particularly Americans, want to make a difference. It’s part of our natural human instinct to want to hear our names echoed into eternity and talked about in history books for the next thousand years.

Almost exactly one year later, Harris massacred 13 people and wounded 24 more at Columbine High School alongside Dylan Klebold. That year, 1999, the movie adaptation of the novel Fight Club topped global charts as the most popular feature films, hailed as one of the most revolutionary films ever made. Of these two events, only one burns just as brightly in American cultural consciousness as it did in 1999. Eric and Dylan had done something Bill Clinton and Cher, in the end, couldn’t do: they had left a lasting impression.

Nine years ago, an “outstanding” graduate social worker named Steven Kazmierczak took a great deal of Xanax, dressed himself up in a similar fashion to the Columbine shooters and opened fire on a university

auditorium, killing six people and wounding 21.

Five years ago, a schizophrenic teenager named Adam Lanza surrounded himself with the storm of press coverage Kazmierczak and the Columbine shooters had gotten, when he stole his mother’s gun and killed her, and then massacred a classroom of 26 first-graders.

One year ago, Omar Mateen walked into a gay nightclub and gunned down 50 people inside, claiming to act on behalf of ISIS – despite being totally unconnected with the group and having been to the Middle East once, for eight days, in 2011.

One week ago, Stephen Paddock, a millionaire and compulsive gambler, fired upon a country music festival from his hotel room in Las Vegas, wounding and killing over five hundred people.

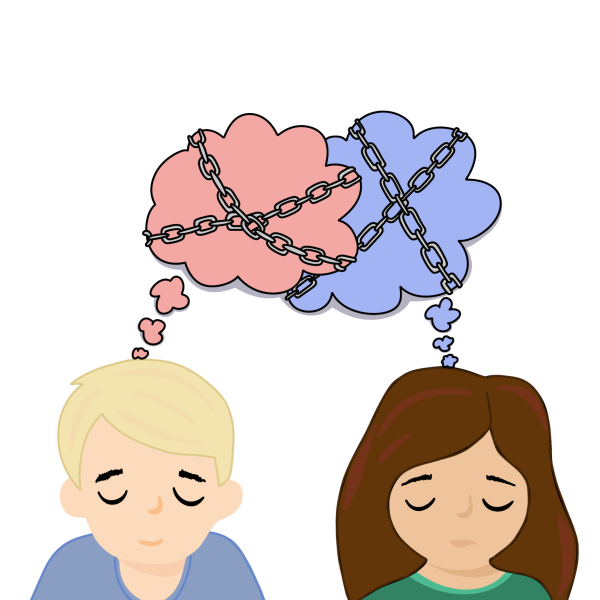

These men are nearly as dissimilar as can possibly be – psychopaths, social workers, schizophrenics, displaced aliens and gamblers. In fact, only one element remains consistent in all of their personalities: an all-consuming desire to be remembered. We know what clothes these men wore the night they opened fire. We know what their families were like, how they thought, what they liked and hated. Hundreds of books have been written on Harris’ journal and Seung-Hui Cho’s deranged plays. They spark enraged political debates that last for weeks and strike at America’s very core. They gain literary cults of psychologists and sociologists that write books decades after they’ve died, probing at every aspect of their mind to release it to the public. They gain the full attention of millions of people for weeks after their ‘glorious’ massacres, and occupy the minds of hundreds for the rest of their lives.

It seems increasingly obvious what motivates and sparks the ever-ramping chain of killings that seems endemic to America. More so than any other country in the world, we idolize and almost, sickeningly, admire these people, probing for every last detail of Stephen Paddock’s life through his stunned relations. Twenty years later, when the unique culture of the nineties has all but dissipated, the legacy of Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold still seems to hold tremendous influence over American direction and thought. Stephen Paddock does not seem to be a drug addict or sociopath: He seems to be a man who has realized a fundamental truth of modern American society: If you want the world to remember you, pick up a gun and outdo your predecessors. If that’s true, then perhaps we won’t be able to pin these massacres on the tool of the killer or overarching mental issues anymore. Stephen Paddock, more than ever before, does not seem to be the kind of killer who would have picked up a gun without a cheering audience behind him. When will we stop cheering?

Contact Max Goldenberg at [email protected].