The Politics of Pop

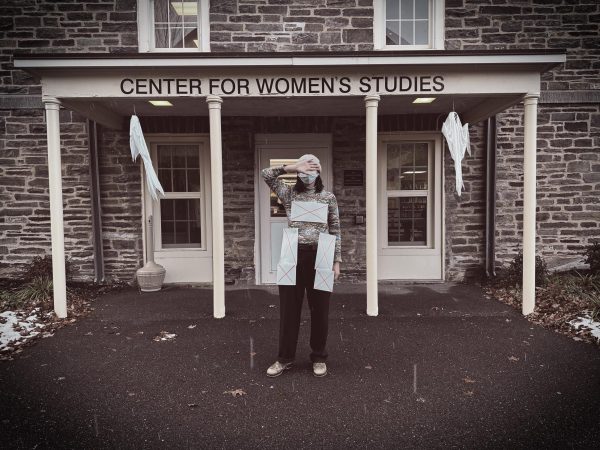

Following Chris Brown’s success at the Grammy Awards last Sunday, I couldn’t help but notice the responses in both mainstream and social media. Indeed, the reactions tended to take one of two opinions: praising Chris Brown for his musical comeback, or lambasting the Grammys for allowing a one-time domestic abuser to perform (and many further attacking Brown’s fans for being okay with it). In a world where the goings-on in the pop music sphere often revolve around fluff and drama manufactured by artists for the sake of publicity, the fact that people still reacted emotionally – nay, harshly – to a largely forgotten-about incident three years ago was a surprising change – and not one without greater implications.

Primarily through blog posts, feminists argued that endorsing Chris Brown is effectively condoning domestic violence, and that the simple fact that he beat his ex-girlfriend Rihanna should preclude him from performing at the Grammys, much less receiving an honor. While I see the point they’re trying to make, I’m not sure I agree; Brown’s violent actions did not stop him from contributing to the music industry and it certainly did not stop him from creating good music (quite the contrary, in fact – troubled backgrounds often provide the best artistic inspiration). As long as character references aren’t a criterion for winning a Grammy, if Brown’s music is deemed worthy, it should be featured. Think of it this way: Roman Polanski’s alleged perpetration of statutory rape didn’t keep him from Oscar nominations and Golden Globe wins because, despite his personal background, he still produced quality work. Why should talent be excluded due to the artist’s spotty history? If anything, the fact that Brown was able to bounce back from the brink of career suicide is only a testament to his musical abilities (or, at a minimum, his aptitude for choosing a publicist). And denying Brown’s many fans the chance to watch him perform because a minority of individuals takes offense to his three-years-past actions is taking a moral high ground I can’t get behind. Besides, why are Brown’s ethical shortcomings any worse than those of other celebrities? Why can the general public let countless stars perform at awards shows after driving while intoxicated (arguably just as dangerous as domestic violence, if not more so) or – double standard alert – getting into a physical altercation with someone of the same gender, while Brown’s domestic violence is overly politicized? Rihanna has moved on, so why can’t the rest of us (and, given the horrors of domestic violence, do we really need to make her keep reliving an incident she wants to move past)? Besides, making music is simply Brown’s job and, like anyone else convicted of a crime, he was allowed to return to work if his employers (in this case, both the music industry and its consumers) saw fit.

Though they may seem petty, the grievances against Chris Brown are actually reflective of a greater trend in society: politics. In an election year, this is especially pertinent. Does any given politician’s personal missteps (think Bill Clinton), no matter how abhorrent, really imply that he or she is any less qualified for his or her position in government? Furthermore, scandal often yields publicity rather than contempt. Newt Gingrich, for example, only enjoyed an increase in his exit poll numbers after news broke of his shameful affairs. And sometimes even the victims of a scandal can benefit from the fallout. Though it may be un-PC to consider, isn’t it possible that the success of Rihanna’s album Rated R, released only months after the domestic violence incident, could be due in part to pity or even to a politically-motivated desire to ensure that her efforts would be more successful than Chris Brown’s? Hasn’t she drawn artistic inspiration from the incident as well?

Though the world of pop music may in some aspects mirror politics, the relative importance of the latter as compared to the former has colored my opinion as to supporting morally questionable individuals. Though I would likely still vote for a presidential candidate with less-than-ideal character if my own politics best aligned with his or hers and I thought he or she would make a competent leader, my choices regarding which pop albums I purchase will have much less of an impact on our country. I’m certainly not condoning the actions of said morally questionable politicians or of Chris Brown, and if you find Brown’s personal life to be so repugnant that you choose not to buy his music, by all means, boycott his work. I don’t even like most of Brown’s music; I’m simply defending his career on principle. Public figures’ personal and professional lives should, by and large, be kept separate. As far as the Grammys incident goes, I simply cannot equate allowing a popular musician to perform at an awards show with condoning domestic violence and, despite what feminist bloggers have asserted over the past few days, I’m not sure I would feel any differently if I (or my mother, sister, aunt, what have you) had directly experienced domestic violence. I also don’t think teenagers are watching the Grammys and suddenly deciding domestic violence is okay (in fact, I doubt the very idea would have entered their minds if feminist bloggers hadn’t put it there); they’re simply appreciating the catchy music and gaudy performances. Don’t try to produce a message that isn’t there – that’s counterintuitive and potentially harmful. Don’t like the actions of Newt Gingrich or Chris Brown? Fine, don’t vote for Gingrich or buy Brown’s music. But don’t tell those who disagree with you that they’re wrong for doing so – or worse, try to shame them – and don’t try to keep either from contributing to their respective field.

Contact Alanna Weissman at [email protected].