Josh MacPhee Explores Art as a Political Tool

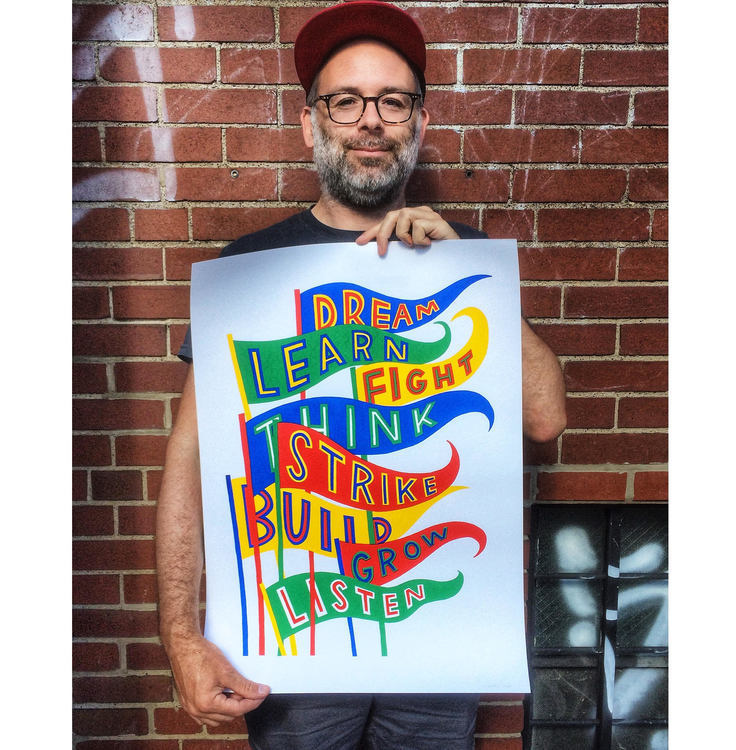

Josh MacPhee is an artist, activist and archivist who is active with the Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative and the Interference Archive. MacPhee gave a presentation on Oct. 7 for the Art and Art History department on formal ideas of art, its subsequent perceived limitations and a transition to using art more flexibly and making art more accessible.

MacPhee explained that what we think of as art is unequal and unethical, being produced in factories and in a non-unique fashion. As such, he spent time debunking the common perception of art.

“We still see art as individual people painting. In reality, art is made in art factories and is done collaboratively,” MacPhee said.

Sophomore Margo Williams said this emphasis on the inequality present in the art industry particularly struck her.

“[The presentation] definitely underscored the hierarchical nature of the art industry, which is something I had never thought about previously. [MacPhee] explained that almost all art today is a product of many contributors, so it should be collaborative, but it often is not,” Williams said.

The traditional sense of art is very narrow and exclusive, but MacPhee showed that art can serve a purpose or a cause. “Art is not neutral,” he added, as art often has political undertones and can be used in social movements.

MacPhee focuses on using art as a political tool with the two artist cooperatives of which he is a founding member. These two groups are the Justseeds Artist Cooperative and the Interference Archive, both based in Brooklyn, N.Y. When talking about the Justseeds Cooperative, MacPhee stressed that this co-op is both collective and collaborative; the 41 artists that make up Justseeds work to circumvent the toxic parts of the art world and to use art to support civil movements. For instance, one movement that MacPhee took part in was the Rikers Island protests in New York City; he helped create black, foam, fists to be distributed. Another movement he collaborated with was the Celebrate People’s History Series which involved creating a series of posters of lesser-known historical figures.

When asked about the interactive part of his job, MacPhee talked about how he fosters personal expression. “We live in a society where we really only have access to personal expression and where collective expression is not allowed or accepted,” he said. As an artist, MacPhee sees the need to create a new type of collectivity in art.

In an subsequent interview with MacPhee, he discussed the intersection of culture, art and history and his work with the Interference Archive, a public collection focused on cataloging materials from social movements. Digital archives are steadily becoming more prominent in the academic field and allow for easier access to a wider variety of sources for researchers. However, MacPhee and his work at the Interference Archive are going in a slightly different direction.

The Interference Archive is more interested in accessibility and getting people to engage with the information. Opposed to traditional, physical archives, which can be seen as exclusive and strictly academic spaces, the Interference Archive has a storefront space where they focus on the collaborative significance of the items in the archive. To determine which objects go in the archive or to determine significance, the Archive holds group sessions where a large number of people come together to decide and explore the items together. MacPhee and the Interference Archive focus on collective aspects of culture and the history behind culture.

Art also plays a role in the everyday public interactions most people have in the form of statues and monuments. This past summer, our country saw the largest outcry against Confederate statues and subsequent response to their removal. One question posed to MacPhee explored his thoughts on the validity of statues in light of these recent events. MacPhee’s response was that monuments are “Architectural documents of history.” Though it could be important to take down items that make spaces oppressive to a group of people, there is the possibility that by taking down statues, we may lose understanding of the past. Popular locations in major cities may not be the correct place for these statues, but there should be a way to use these objects to acknowledge and better people’s understanding of history according to MacPhee.

Finally, in discussing the interactions between art and history, MacPhee argued that everyone should feel ownership over culture and history, and that both can work together. The more public the art, the more interesting; the more we move away from the canvas, the more people can interact with art and history.