Long Story Short: Exploring Poverty in Northern and Southern California

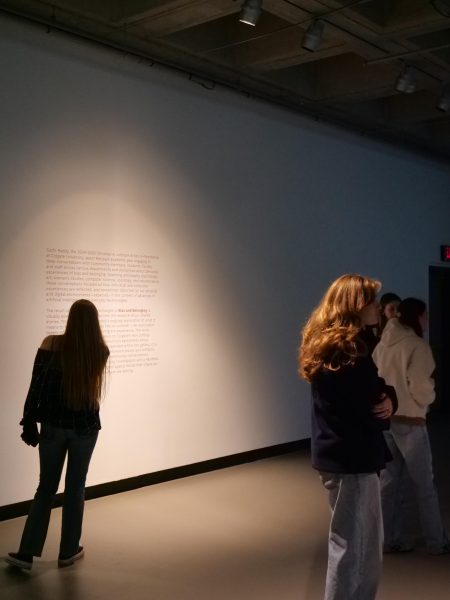

The voices of over 100 impoverished individuals living across California echoed throughout Golden Auditorium on Friday, September 22. Over the course of 45 minutes, director and artist Natalie Bookchin took viewers on an emotional and surprisingly intimate journey with her film Long Story Short. The 2016 documentary paints an honest picture of poverty in the U.S. through the interweaving of interviews with individuals on food stamps, in homeless shelters and in job-training centers.

The Women’s Studies Department co-sponsored the event and chose this documentary for the Friday Night Film Series because it was the grand prize winner of the Cinema du Reel, second prize winner for documentary feature at the Athens International Film and Video Festival and winner of the Sebastopol Documentary Film Festival in 2016. After Associate Professor of Film and Media Studies and Women’s Studies Mary Simonson gave a brief introduction on the importance of the film, the screen was illuminated with the faces of individuals describing an inescapable feeling of helplessness.

Overlapping testimonies from real people brought awareness to the common threads in the lives of impoverished Americans. The film opened by talking about underlying race issues that left many disadvantaged from birth, and the shocking reality of the importance of money in everyday life.

One man described money as “the new form of slavery,” while another claimed “you need money to feel like a person.” From being hungry for days to struggling to raise a family on $516 of welfare money a month to lacking the funds for basic hygiene necessities, existing on such a miniscule income proved unavoidably grim in today’s capitalist world.

The hypocrisy in statements such as “just get a job” were also debunked by the film. Many individuals commented on their desire to work and keep a job, but asked how they could possibly achieve that when they do not have a physical address to fill out on official forms or a phone number for interviewers to call.

“The mailman won’t deliver your job application to your car,” one man said.

Many interviewees had multiple college degrees or cosmetology licenses, and stated that they became homeless even while maintaining a job; their wages simply couldn’t cover rent. One woman’s house burned down and another man was laid off for missing work due to ongoing HIV treatment. Ultimately, homelessness can affect anyone regardless of how much it may seem as though they have their life together.

Individuals frequently described their lives as “a living hell,” while commenting on how degrading life without money can be. While some did things they never would have thought they could do, others said their bodies physically wouldn’t let them beg. Although pity was abundant, compassion was incredibly lacking among the rest of society.

The road to poverty came from unfortunate accidents for some, but others were set up for failure from birth. Raised in drug-ridden communities, witnessing family members getting shot by rival gangs and the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) alike and surrounded by an unimaginable amount of violence, these people lacked role models.

“This is all I saw, this is all I knew, so this is what I became,” one California citizen said in the film.

Ultimately, the sense of helplessness seemed all-consuming for Americans living in poverty. Representation is virtually non-existent in politics and the voices of the lower class often do not get heard. What is equally damning, the film charges, is the judgement and lack of empathy poor people continuously face.

As the voices and images of real people gradually disappeared into a black background, one final comment resounded: “You’ve thought it.” As the audience sat and watched the credits and the images of every individual interviewed fly by, the reflective silence felt both heavy and deafening. Clearly, no one is blameless in regards to the way society looks at and thinks about the less fortunate. Ending the stigma and contributing to valid, applicable solutions can only come through widespread awareness and a universal desire to fix what is fundamentally broken in our country.

Long Story Short may only have played for 45 minutes, but the ideas discussed remained long after the screen went black.

Contact Lauren Hutton at lhutton@colgate.edu.

Lauren Hutton is a senior from Pembroke Pines, Florida double concentrating in Women’s Studies and English with a creative writing emphasis. She has...