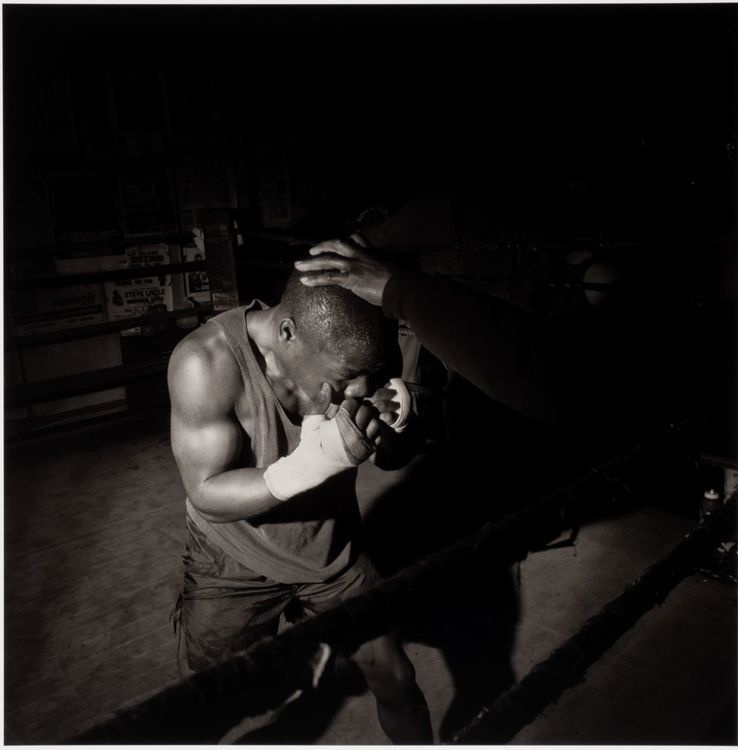

Violence as Tenderness: Larry Fink’s Beyond the Gloves

PICKER ART GALLERY: Photography by Larry Fink depicts the intimate moments behind the bloody sport of boxing.

The sport of boxing is a paradox: men come together in an endeavor to savagely tear one another apart, all the while looking somewhat spiritual with their swollen noses and missing teeth. This intimate contradiction is what Larry Fink looks to explore in his work, and is put on full display in the Picker Art Gallery’s most recent exhibition, “Beyond the Gloves.”

With stark black-and-white closeups of faces shining with sweat, men holding each other in what could nearly be an embrace if not for the blood on their faces, fighting becomes something beautiful and sensitive. In a sport known almost entirely for its brutal machismo, there is a closeness between men that permeates each claustrophobic shot and the glorious, muscled outlines. Fink’s photography is reminiscent of renaissance art – silence is baroque, and manhood is performed to the highest possible degree.

Fraternity is a central component of this exhibition: how do men relate to each other when masculinity is viewed as antithetical to intimacy? Fink’s answer to this question lies in the moments captured in spare, gray rooms, between coaches and athletes, athletes and athletes and athletes and themselves. Fink’s spectators, who are almost entirely men, are similarly brought together by love expressed through violence. They sit together (nearly touching, but not quite) biting their nails and eating popcorn, their shadowed faces completely focused on the middle-distance.

Rage and ecstasy reign supreme in the boxing ring, but it is not a world entirely removed from social issues: traditional conceptions of masculinity are at the forefront.

“Boxing is a sort of microcosm for a lot of phenomena we see in America on this smaller scale we don’t really think about,” said senior Jessica Rosen, who curated the exhibition. “In the media that you see about boxing, it tends to be showing champions, fights, brutality, and actually erases a lot of nuances in the boxing world.”

Masculinity, at points, can even act as its own foil. A man with gloves on needs his shoes tied, his brow wiped and his blood cleaned by other men.

“Boxers can simultaneously be the strongest person in the room, and as soon as the gloves come on, they can’t do anything for themselves,” Rosen continued, “This setting gives men permission to be vulnerable without sacrificing their masculinity. Only in this context can we have these really gentle moments take place.”

Homosocial relationships among men are rarely open in their expressions of love – rather, they are, as Fink portrays, veiled with brute force and occasionally even cruelty.

“Because of toxic masculinity, men showing any signs of vulnerability in emotions or sensitivity towards something is seen as weak,” said sophomore Ethan Freedman, who identifies as male. “There is no room to let your guard down and be emotional without feeling like you are performing masculinity incorrectly.”

As Fink sees it, truth lies in the performance of masculinity, and the careful dance of power and tenderness that boxing relies upon.

“Social ideas of masculinity result in a series of expectations that may result in behavioral conformity,” said first-year Will Monti, who also identifies as male. “Expectations that more forward or dominating behavior is expected or acceptable are pervasive.”

In a perfect world, two men might be able to comfortably and platonically say “I love you” without needing to follow it up with a feverish “no homo.” Until then, however, we live in Fink’s reality, wherein affection shows itself most clearly in a bloody nose or a swinging fist.