Bill Moore and the Psychology of Conscious Awareness

At 14, Colgate Athletics’ mental performance specialist Bill Moore was in Florida. His evenings passed under the bright sun of tennis courts. Here, he coached kids. He coached them in exchange for tennis lessons. He knew, from his first day volleying, serving and encouraging youth as they gripped child-sized racquets in their hands, that he wanted to spend his life in the sphere of athletics, as a man who would guide others and help them reach their potential.

At 17, tennis again contributed to Moore’s career journey. It was at this time that he read Tim Galwey’s “The Inner Game of Tennis: The Classic Guide to the Mental Side of Peak Performance.” Moore noticed that, in the world of sports, much information was accessible on skill development, but very little on sports performance.

Moore’s interest and understanding of sports psychology expanded at the University of Virginia (UVA), where he earned his doctorate in sports psychology. Here, Moore played club tennis. He observed other members on the club’s team. One group of players, without fail every day, would come early and stay late, while another group hardly ever practiced. However, the latter group performed much better in matches than the former.

Since his graduation from UVA, Moore has published five books on the psychology of human performance and founded the consulting agency, BeMore Consulting, through which he has worked for 25 years with athletes, universities, musicians and business professionals. How does one individual accomplish so much? Moore practices the psychology he preaches, maintaining careful discipline and routine in his daily life. To give you a taste of the discipline Moore practices daily, he goes to bed at 9:30 p.m. and wakes up at 4 a.m. each morning.

One of Moore’s first steps in his career journey was at the University of Oklahoma, working as director of mental training. While in this position, Moore received a call from Oklahoma’s music school, asking him to teach a course titled “Performance Psychology of Musicians.”

To Moore, there are great similarities between the Colgate athlete and the music students at Oklahoma.

“They are somewhat perfectionistic, somewhat overachieving, tend to think a lot and strategize a lot.”

He urged in his athletes the same psychology that he presented to music students: A mindset of “conscious awareness.”

“When you start talking about running, hitting, throwing there are hundreds of thousands of bits of information that need to be processed. It’s all below our awareness. If you want to mess up an athlete you make them aware of this,” Moore explained.

It is important that the conscious mind and the unconscious mind are attuned to one another, Moore explained.

“When athletes are trying to be correct in their movements, that’s at the crux of how things break down in performance because you can’t try to be correct and perform in a free and effortless state. Those two things are diametrically opposed. So you can either try to be correct in your movement or you can be free and play.”

Moore’s work at Colgate focuses on helping student athletes to understand the difference between a practice and performance mindset. Colgate students are receptive to Moore’s advice and instruction. A mindset Moore works on with the athletes in performance is to accept mistakes and slip-ups. The game keeps going.

“What’s nice about Colgate is they tend to be good kids, respectful, come early and stay late and want to know how to fix things,” Moore says. “It’s a double edged sword because they want to know what they did wrong and how to fix it.”

Moore also works with Colgate’s coaching staff.

“Coaching performance is more nuanced than skill development,” he said. “The mental and emotional aspects of performance are important but very few people know how to train it. … I really like working with coaching staff to help them because it needs to come through them.”

Broadly, Moore wishes that he would see the psychology of practicing freedom and flexibility in athletics in the broader sphere. The return of “sandlot sports,” or casual sports play between friends, neighbors and family, is something that Moore misses and encourages. These sports are vital in shaping flexible, happier athletes.

“In sandlot sports, if we could take that mindset and attach it to the head of an instrument that is super strong, super fast, well trained, you have the performance. Today a lot of kids have never played sandlot sports. It’s been adult controlled, uniforms, instruction.”

Moore calls for the end of the mindset of “I need to be correct.” He urges students to think about times when they played sports freely and had fun because mistakes were not the focus – because mistakes paled in comparison to fun and the larger game.

“We want to take that mentality and plug it into kids today and they’ll perform a lot better,” Moore stressed.

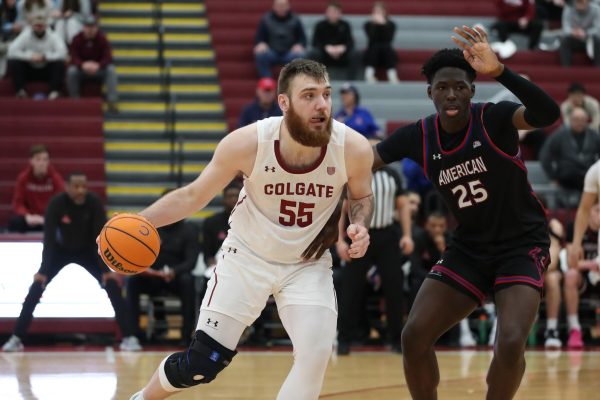

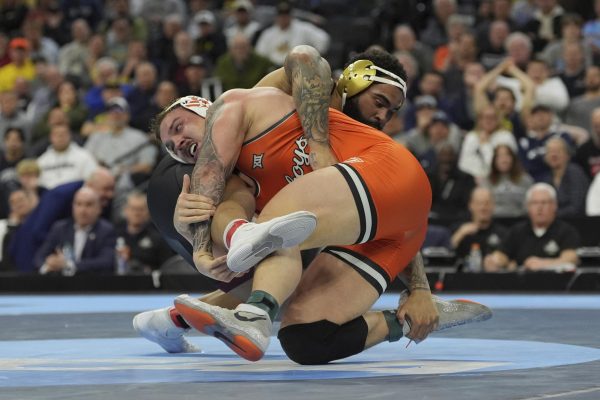

What are Moore’s favorite memories at Colgate? It comes back to family and fun. He loves spending free moments with his wife, Nicki Moore, who works as vice president and director of athletics, and his son, Ian. Recently, they enjoyed going to the NCAA basketball tournament and the women’s volleyball championship.

“If I had to pick a great moment at Colgate,” Moore said, “it would be something with Nicki and Ian.”

Bill and Nicki Moore’s son Ian knows all the security people at the arenas by name. He is now so friendly and well-known in the community, that Colgate staff deem him “mayor.” Ian, much like his parents, shows great interest and investment in the Colgate community. The integration of the whole family into the Colgate community is a reflection of the psychology of engagement and fun that Moore so urges.