Unpopular Opinion: Fiction and Nonfiction Are Equally Important

Your literature collection should be full of fiction and nonfiction, not one or the other.

For a lot of people, reading has always been a bore. Throughout primary and secondary school, we’re taught the importance of reading both within and outside an academic setting. While regularly engaging with literature is undoubtedly beneficial for a variety of reasons, this article is not intended to convince non-readers that they should pick up a book.

Trying to persuade an audience to do something that they have been subtly programmed to detest their entire life within 700 to 800 words would be too ambitious. Instead, I’m more interested in bridging the gap between fiction readers, who consider nonfiction to be inaccessible, and nonfiction readers, who feel that fiction is low-brow.

For all students at Colgate, learning to critically engage with literature, nonfiction and fiction is one of the hallmarks of liberal arts education. And yet, most Colgate students (and people at large) who read for pleasure would probably say that they mostly, if not exclusively, read fiction outside of an academic setting.

Within smaller humanities classes such as a student’s first-year seminar, there is an expectation that every student participates. Professors are eager to understand how you engage with a text and how you formulate your arguments using that text. However, the seemingly insurmountable anxiety that comes with constructing an argument to engage in discourse with your classmates is enough to discourage most students from reading dense nonfiction akin to what they read for class.

However, I would implore you to explore the possibilities that come with reading books such as Discipline and Punish by Michel Foucault or Fearing the Black Body by Sabrina Strings. Books like these not only show you the history of social constructs but also force you to confront preconceived notions about how these constructs influence our daily lives.

Reading for pleasure should be intimate. Once you remove yourself from the high-pressure environment that is a classroom at an exclusive university such as Colgate, you can begin to engage with nonfiction in a way that feels organic.

When you’re reading nonfiction for pleasure, the books, articles and essays you read should be picked by you, in the same way that you would pick a novel. By no longer confining yourself to a curated list of topics, like you do when you’re taking a class, the learning process becomes more investigative. You get to explore subjects in ways that relate to you, and there are no stakes as the anxieties of a paper or class discussion cease to disappear. And when you do converse with someone about what you’ve learned from a work of nonfiction, you can be honest and open about what you don’t understand or what you find compelling without worrying about the articulation of your ideas being graded or scrutinized.

Despite what nonfiction readers might think, reading fiction is as important as the esoteric texts that you bloviate about to your intellectually pompous friends. Unlike fiction readers, people who read nonfiction tend to see information as more valuable when it’s presented argumentatively. Regardless of whether this information subverts or upholds a popular idea, most nonfiction readers would agree that essays and books are more rhetorically effective than stories. But why?

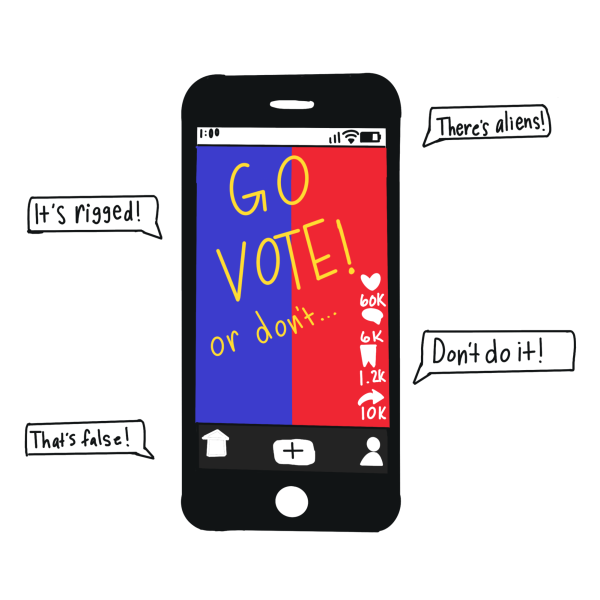

Ironically, the proliferation of anti-intellectualism in the past few years is to blame for this. Unless you live under a rock, you’ve probably seen memes about how English teachers frequently extrapolate the significance of minor details in efforts to start discourse amongst their students (i.e. the curtains being blue is a metaphor for the protagonist’s depression). While this can occur, storytelling is invaluable to understanding the mechanics of our intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships within the context of sociological phenomena.

In my senior year of high school, I took an English class called Radical Love in African American Literature. After reading Audre Lorde’s essay collection, Sister Outsider, and her semi-autobiographical novel, Zami, I began to draw parallels between her alienation as a black woman amongst white lesbians and as a lesbian amongst cisgender, heterosexual black women both in her essays and novel. Although Lorde’s essays in Sister Outsider directly inform her writing in Zami, non-fiction can always be utilized when analyzing fiction and vice versa.

Instead of framing fiction and nonfiction literature as dissonant in the same way that scholars tried to argue that religion and science were for decades, you should understand that they have a mutual relationship and inform each other constantly. The essay and the story are the foundation for how we learn and think. Without appreciating and consuming them simultaneously, it is much harder to make sense of the complex world we live in.