Mother Earth and Man-Made Disasters: How Climate Change Rhetoric Harms Women

Andrew Tate’s name was not one I was well acquainted with. However, after his Twitter exchange with Greta Thunberg and his arrest for rape and trafficking in Romania, I began to familiarize myself with the social media personality who produces hypermasculine content.

In an apparent effort to provoke Thunberg, Tate first tweeted about his extensive car collection, asking the teenage climate activist for an email address to which he could “send a complete list of [his] car collection and their respective enormous emissions.” Thunburg shot back: “yes, please do enlighten me. email me at smalldickenergy@getalife.com,” she tweeted.

The exchange didn’t end there. Tate tweeted a condescending video at Thunberg, but just one day later, he was arrested. In response to (now-disproven) rumors that the pizza boxes pictured in the video helped Romanian officials locate and arrest him, Thunberg tweeted, “this is what happens when you don’t recycle your pizza boxes.”

The Twitter clap back prompted me to think about climate change and environmental issues through a different lens. One would assume that climate change is a topic that transcends gender — after all, we are one human race that inhabits the same earth. Shouldn’t we all care about our climate equally?

As a culture, we have long made climate change a gendered issue. It is embedded in the language we use to describe the issue. We often refer to human-induced climate change as a “man-made” disaster. We refer to our Earth as a “mother.” Our rhetoric has shifted climate change from an issue of humans at odds with the environment to men at odds with women.

While perhaps the use of “man” in the phrase man-made disasters is merely a function of the English language, its implications are not incidental. While all humans are responsible for the anthropogenic destruction of the planet, it seems obvious to me that men have played a greater role in this. In a 2018 study, political scientist Cara Dagget found a connection between masculinity and the use and control of fossil fuels: “Fossil fuel extraction and consumption can function as a performance of masculinity,” she writes, “even as it also serves the interests of fossil capitalism.” Not only do men control the fossil industry, as Daggett states, but they also dominate the fossil-fuel-reliant military, drive larger vehicles, on average eat more meat and participate in recreational activities that require more carbon— all actions that contribute to this “man-made” environmental harm.

To describe human-induced climate change as a man-made disaster to the planet is to accurately identify its greater general perpetrator.

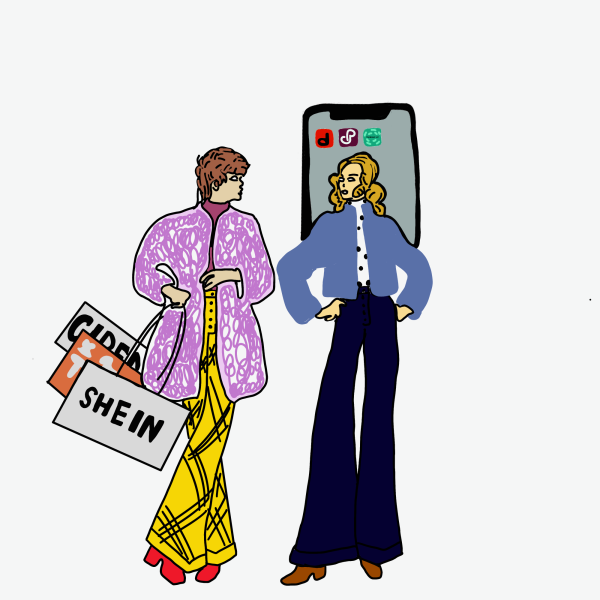

This is not to say that women are absolved from climate sin. Climate change is a human-induced issue and all people bear some responsibility. In fact, many women — particularly white women — have benefited from the masculine fossil fuel culture, which Daggett dubs “petro-masculinity.” However, women disproportionately suffer the effects of climate change.

Women are more likely than men to suffer as a result from climate change. The International Union For Conservation Of Nature (IUCN) found women, boys and girls are 14 times more likely than men to die from a natural disaster. Additionally, according to a 2005 study cited by the IUCN, domestic and sexual violence toward women is heightened following a disaster.

In addition to these threats following a natural disaster, women are designated as the keepers of the planet. We refer to the Earth as a mother and expect women to care for the Earth the way the Earth cares for us. According to the United Nations, women face an unequal responsibility in securing natural resources of water, food and fuel. In lower-income countries, women are primarily employed in agriculture. The unstable conditions brought on by climate change pose not only a threat to women’s health and safety but also their livelihood.

We view the Earth as feminine not only in the context of climate change but also in terms of land ownership. Our home country is our “motherland” or “mother country.” In this mother country, we speak our mother tongue. Feminizing land allows them to feel a sense of power over it, to feel the need to protect this vulnerable “mother” who is left defenseless. Earth, a perceived feminine entity, has been viewed as less powerful and therefore something to control rather than respect.

Is it emasculating to care about the environment? Is it feminine to want to preserve the earth for future generations? Earth is not a mother who takes care of us unconditionally. Earth is also not a woman in need of saving.

To change our outlook on climate change, we must change our rhetoric. Framing climate change as mother earth suffering from man-made disasters fosters a culture of men against women in the conversation surrounding climate change, when we should be working together. Climate change is an issue that affects all of us, regardless of gender. We must cross these barriers and work to mitigate climate change, or we will all suffer the worst of its consequences.