Professor Hill on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion for Women’s History Month

Assistant professor of women’s studies Dominique C. Hill has devoted her life to issues of injustice through avenues of race, social status and gender. A graduate of Colgate University’s class of 2005, Hill’s unique perspective on secondary education institutions and the ways in which they interact with a diverse student body provide important insight to students struggling with how or where to make change.

“I was always drawn to issues of injustice; always interested in the power of narrative, and the type of stories that come out [and] the relationship to the people who tell the stories,” Hill said. “[I was motivated by] being able to take a class as an undergrad where I was challenged to think about that history in terms of how the field was created, but also in terms of our literal classroom.”

Hill’s critical analysis of the world, including systems of higher education, both within and outside the classroom, helps to provide insight into the dangers of a society intent upon inclusion, but ill-equipped to initiate it. In the classroom, Hill is acutely aware of the power of a narrative’s language to overwhelm and corrupt a conversation.

“Even when we use words like ‘female’ we’re leaving out and creating a set of assumptions about who get to be women; who get to be recognized as women,” warned Hill. “There’s a history of that term being designated around lines of race, around lines of class, around lines of sexual expression.”

Hill explained that even entering the field of women’s studies with the assumption of certain characters being part of the conversation can prove dangerous to the movement towards equality. To address these questions, Hill implements a variety of strategies within the classroom to facilitate a comprehensive conversation.

“I like to teach through the idea of the feminist project, rather than thinking about a [specific] movement, primarily because there have been multiple movements in the name of addressing inequalities, whether it be woman-focused or about women at large,” Hill mentioned.

This approach largely originates from a need to address assumptions which students may or may not hold upon entering the field of women’s studies. As a professor, Hill has taken on the responsibility of presenting students with certain voices and narratives which, far from excluding the voices of some, serve to raise up or otherwise encourage the sharing of others.

“I want to make sure that people understand that even though narratives may foreclose or streamline who’s been a part of the work, that the work of the project [extends] across time, across space. […] [If we understand that] then we have a more capacious understanding of what is the work, who has been involved, what’s still left to do and what are the interrelated tensions and issues which need to be addressed.”

Hill explained that her area of study, Black girlhood, has remained especially prevalent, not only in its individual importance, but also in its widespread application to other areas of oppression and injustice due to its common texture with other experiences. These commonalities among groups facing injustice extend beyond barriers which would initially seem to divide them.

“We can think about body policing, for example, as something that happens to all of us; even when we can be identified as the ideal body, [or] come from privilege […] folks are still organized around attention to one’s body. [Injustice] may show up differently by nature of context,” Hill said. “One’s skin complexion, one’s sartorial [way they decide to comport], the way they dress. […] The textures get a little different, but there is a common texture to experiencing and navigating oppression.”

Hill’s studies have also revealed dynamic relationships between such issues as race and gender.

“[Feminism is] belief in the equality of the sexes,” said Hill. “But when we say equality of the sexes, women don’t want to be equal to men of color or lower socioeconomic status men.”

The question of gender has long been analogous with other questions of identity, including race. Despite becoming more recognized in recent history, Hill believes that there is still a long way to go in terms of being able to talk about these issues without omitting certain experiences or perspectives.

“Intersectionality is a term that was named by Kimberle Crenshaw. […] I know it gets misused across space because it’s been popular within higher ed,” Hill said. “Crenshaw was trying to create a framework for how social categories of difference interweave, and how they are already interwoven, and how their interweaving creates differences, specifically initially for Black women looking for employment.”

Hill maintained that, despite being an important part of reaching a more understanding and inclusive society, “intersectionality” does not encompass everything.

“It’s not just about the ways in which all of your identities intersect — that is the thing, but it’s not the framework. You apply the framework to figure it out. For instance, how is it that in terms of schools, Black girls are overwhelmingly suspended and punished for dress code violations?” questioned Hill. “What is it about [that] coming together of Blackness and gender?”

Hill uses the term “feminism” not as a descriptor or as a title, but rather as an ongoing and ever-changing progression of society towards a place where discrimination against women is significantly lessened through acts of protest and declaration.

“In many ways it was created out of protest to say that women’s lives have value, women are knowledge-producers. […] Women’s ways of knowing the world [are] an important pursuit and contribution,” Hill said. “We have to understand that feminism as a project has to be more than identity — it has to be about the work that you do, [and] it has to be about the politics that you hold. […] Fighting can look like dancing, fighting can look like art. The project [of feminism] has to be a bunch of people with a bunch of ideas, a bunch of tactics and a bunch of strategies doing what they do to work toward the eradication of domination.”

The individual role of those who undertake the project of feminism can vary and change over time, adapting to lifestyles and other aspects of identity.

Hill explained, “When I talk about the project and my intention on moving away from the language of the feminist movement, [the word] ‘project’ to me feels like it’s effective in the sense that we already know that when we are doing a project there are multiple moving parts. […] People should pick up the part that they think they can play.”

Hill believes that part of this work can be informed by the roots of the feminist movement.

“Part of the work going back to the start of the field […] is something called feminist consciousness raising […] which is raising one’s individual awareness about injustice, what kind of forms it takes, what kinds of different factors play into people’s reactions,” Hill said.

Observations of movements over time have helped to guide Hill in what needs to be done to inspire change. One of these parts is allowing artistic movements to speak alongside intellectual movements.

“[There are] different registers at which the project is trying to help people realize that all of us are interconnected,” added Hill. The ability to reach as many people as possible in order to further a project is critical, especially in modern-day America and the industrial world at large. […] Everyone at some point will experience harm [due to capitalism]. It becomes important that we each do our part, and that we each call forth co-conspirators more than allies.”

These assertions are not always met willingly or with grace. Instead, many reject the ideas which are becoming more and more difficult to ignore as the perspective begins to shift in favor of those who may have been marginalized in the past.

“I would say that I’m definitely [myself personally and the field in and of itself] up against the politics of narrative,” admitted Hill. “No doubt in any type of […] revolutionary undertaking, any type of push against the status quo, there are going to be different voices, different ideas about how to do the work, and that is healthy. […] What becomes difficult is the politics of narration, which has popularized who is doing the work. If the popular narrative has been that feminism is an identity and started with the suffragettes, people forget that the suffragettes had to learn the idea of equality from someone, plus that the sort of strategies and tactics that people employed were learned within the abolitionist movement.”

Even if tensions between differing sides of a movement may spark conversation and ultimately lead to understanding, this is reliant upon many factors, especially upon who is given a voice. The ability and willingness of students to accept a different perspective is largely dependent on what perspectives they have already been exposed to, and therefore what perspectives they have already determined to be “true.”

“When you try to teach that messy, complex yet real history, if students have been taught a set of history that leaves that out, of course there’s going to be tension,” Hill said.

A significant portion of these partial histories neglect to mention the role of women of color in promoting ideas of celebrating differences and diversity.

“Black feminism has really pushed the field to prioritize and recognize the strength of difference … whereas difference in general society has been [thought of as] something that needs to be fixed,” Hill explained. “The work that has been done within the field and spearheaded by women of color, Black women, queer, trans women, has been about this sort of push to invite us to think about, ‘what would our world look like if we saw difference as a strength?’”

For Hill, Colgate resembles an important portion of society at large, and therefore can benefit from the same types of movement that have been effective in inspiring change throughout history. Largely overlooked by the population at large, small acts of compassion can prove just as effective in promoting equality and diversity as larger acts of defiance or protest.

“I tend to oscillate between what is perceived to be very small work and what is seen to be structural or systemic work, and I think that one of the things that seems small but that is huge is students and folks who are doing and organizing […] clubs and all the busy stuff of the cocurricular taking time to actually be with each other, not with the business and the popularity of it all, but to really try and figure out and actively listen to what is going on,” said Hill.

The role of such organizations can be an integral part of fostering community on Colgate’s campus. Hill says, “As someone who has graduated from here, I’ve never seen so many people involved yet expressing not having community.”

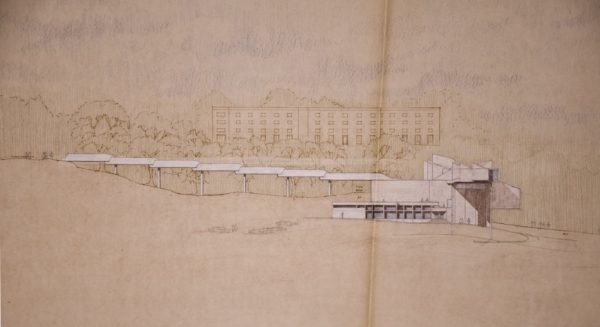

Hill ended on an optimistic note: “I think with all the vibrance that is [at Colgate], I think with the third century plan initiative, I think with the voice of the students, I think we can stand to challenge ourselves a little bit more about how we appreciate difference and how we fold that into the look and the feel of our campus, and not just in bodies.”

The role of Colgate students, Hill said, is simple: appreciate differences without judgment, and adopt a perspective of unity despite, and maybe because of, these differences.