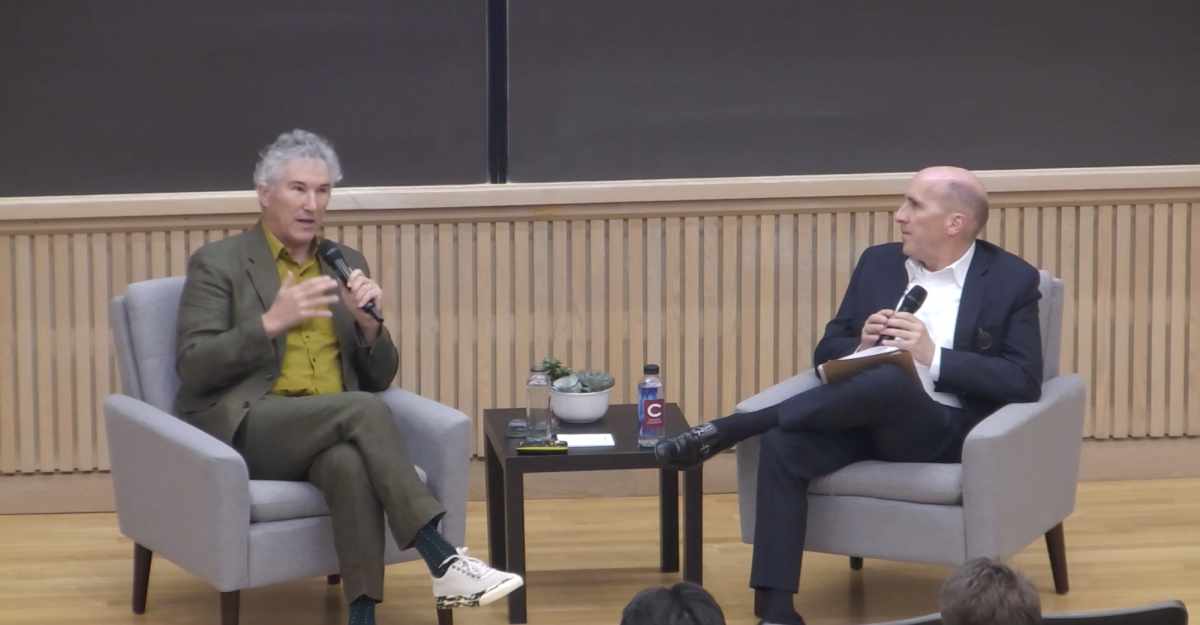

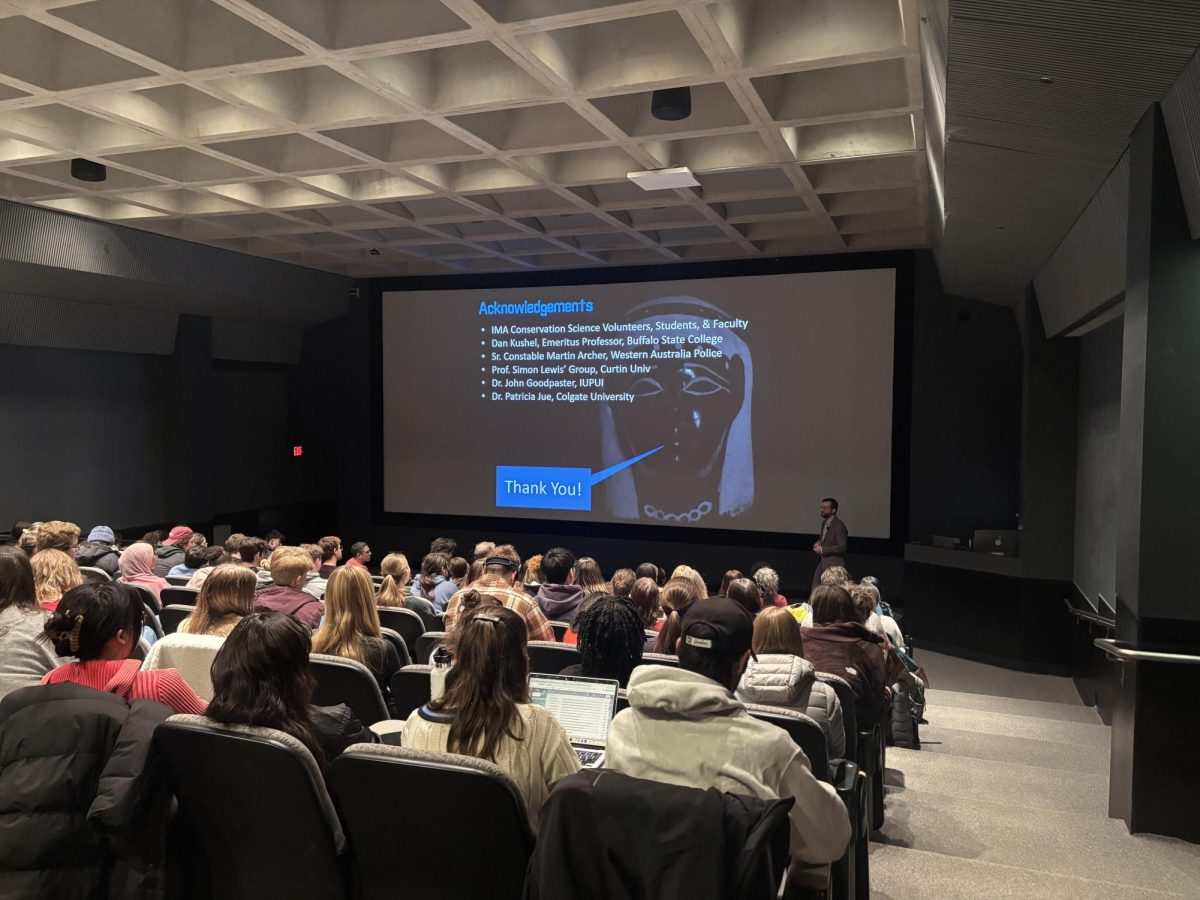

On Wednesday, Sept. 27, the Colgate department of history hosted Rachel L. Swarns, acclaimed author, professor of journalism at New York University and contributing writer for The New York Times. Swarns broke the story of the 272 Black people sold into slavery by Jesuit priests to save what is now Georgetown University and spoke to attendees about her experience uncovering this story.

In January 2016, Swarns was working as a correspondent for The New York Times when her colleagues informed her of exclusive information they had received from a Georgetown alumnus about the university’s well-kept history.

After months of archival research, interviews and genealogy work, The New York Times published Swarns’ article, “272 Slaves Were Sold to Save Georgetown. What Does It Owe Their Descendants,” in June 2016. Swarns hoped the article’s release would affirm Black people’s place in the history of the Catholic Church.

“Slaveholders built the first archdiocese, the first cathedral, the first Catholic seminary, the first Catholic institution of higher learning. The very underpinnings of the Catholic Church were built by priests that relied on slave labor,” Swarns said. “All of this came at a terrible, terrible cost. Scores of families were torn apart and would be completely forgotten for almost a century.”

Swarns shared that her focus was on finding the families of the enslaved. She published a companion piece with the passenger list from the slave ship, urging people to reach out to The New York Times if they recognized a family name.

Today, there are 6,000 known people with lineage to the 272 enslaved people. Swarns remained determined to reunite separated family members via genealogy work and grow the online network of descendants. On Labor Day weekend, there was a gathering for descendants living in Maryland.

“We’re stitching back together the families that were torn apart back in 1838,” Swarns said.

Swarns’ 2023 book, “The 272,” pieced together the sale through the eyes of the Mahoneys, a Black family enslaved by the Jesuit priests for generations. Swarns emphasized mother Louisa Mahoney’s fortitude, even in the face of injustice and oppression.

“Wealthy Catholics burned her contracts and forced her into slavery. She lost everything — except for her story. And she told anyone that would listen,” Swarns said. “It’s a story of heartbreak. But it’s also a story of resilience, family and faith.”

In writing this story, Swarns thought deeply about the enduring faith of Black Catholics.

“One of the things most striking to me, as I conducted this research, is that many Black families betrayed by the church decided to stay. They thought the Catholic Church did not belong to these sinful white men,” Swarn said. “They believed that they could and would push the church to be more reflective of and more responsive to the needs of Black Catholics.”

Dan Bouk, history professor and department chair, admired Swarns’ panoramic, thought-provoking storytelling.

“She manages something remarkable for a historian and journalist: she takes the past on its own terms, allowing us to understand the lives and choices of the enslaved and also the stories and complicated worldviews of those who enslaved them,” Bouk said. “At the same time, Swarns’ work asks us to grapple with what we should do today about past injustice, how we cope and how we attempt to repair.”

In response to Swarns’ article and a series of student protests, Georgetown established a $400,000 Reconciliation Fund for the descendants, and the Jesuit church pledged to raise $100 million.

Swarns acknowledged these efforts but stressed that the story is far from over.

“There is still a lot of unfinished business. This history is not just about Georgetown. It’s not just about the Catholic Church. It’s about every institution with legacies steeped in racism,” Swarns said.

“Our own institution’s story is very different from Georgetown’s, and yet we too have to wrestle with difficult histories, including the way Colgate and its faculty placed the unity of the Baptist Church above the cause of abolitionism [and] repeatedly shut down student-led abolitionist organizations in the years before the Civil War in the U.S.,” Bouk said.

First-year Josephine Jenne was struck by Swarns’ enduring commitment to this cause.

“She has the ability to recognize past wrongdoings in some of the world’s oldest institutions, and instead of simply abandoning the establishments that have done wrong, works within such institutions to create change,” Jenne said. “It is amazing to hear her perspective and encouraging to witness how someone rises above past immorality by emphasizing principles of progress, faith, resilience and respect.”