Exhausted with an unbridled determination, or perhaps vulgar pride, Amory, the main character of “This Side of Paradise,” ends the novel slouching unimpeded towards Princeton University. I first incurred this novel with great torture and unresolve this past summer. Though written more than 100 years ago, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s work was a prophetic prediction of the 1920s and stands uncomfortably relevant today. Fitzgerald follows the progressive decay, or metamorphosis, of societal values through Amory’s life, success and later dissolution. The novel, “This Side of Paradise,” was published in 1920 to financial success and critical acclaim. Looking back now, however, the greatest American writer precisely captured the progression of society from the Victorian era into the brave new world of flappers, jazz, sin and salvation.

Amory grows up coddled and blinded by wealth. His fixation on the grand causes of the past — the Confederacy and the Bonnie Prince of the Scots — damn him to live in a romantic disconnect from society. His family is wealthy, but he is sent away to boarding school when his mother experiences a mental break. Resolved to go to Princeton, the devilishly handsome Amory pursues life anew, trying to find the romantic in the mundane. What he experiences, however, is a world changed dramatically that no university could prepare him for. We see the roaring twenties tear Amory apart. It is important to note Amory’s name is meant to be a wordplay by Fitzgerald, coming from the Latin ‘amare.’ This is the great irony: a character named after love, yet unable to find it.

“This Side of Paradise” poses great philosophical questions of the changing world and is significantly relevant today. Replace the roaring “petting parties” with modern “hookups” or “situationships,” you will incur a portrait of America that is sickeningly similar to the modern day. We see ourselves in the illusion that yielding to lust may – to a cosmic impossibility – yield unrequited love. Thus, the centurion novel asks us to consider what kind of paradise we inhabit. Is it an illusion of romance and opulence? Or is it that reality of truth, where paradise is lost?

Through his time at Princeton, Amory falls enamored with the beautiful Rosalind Connage; however, due to the dissolution of Amory’s wealth, the two find themselves driven apart. Painfully, the piece asks us as an audience: Can love truly conquer all? Later on, the drifter falls for the flapper and atheist Eleanor Savage.

“Beauty and love pass, I know… Oh. There’s sadness, too. I suppose all great happiness is a little sad. Beauty means the scent of roses and then the death of roses.”

Like the rose, we realize we all must die, as will love. But if love inevitably dies, is it worth pursuing at all?

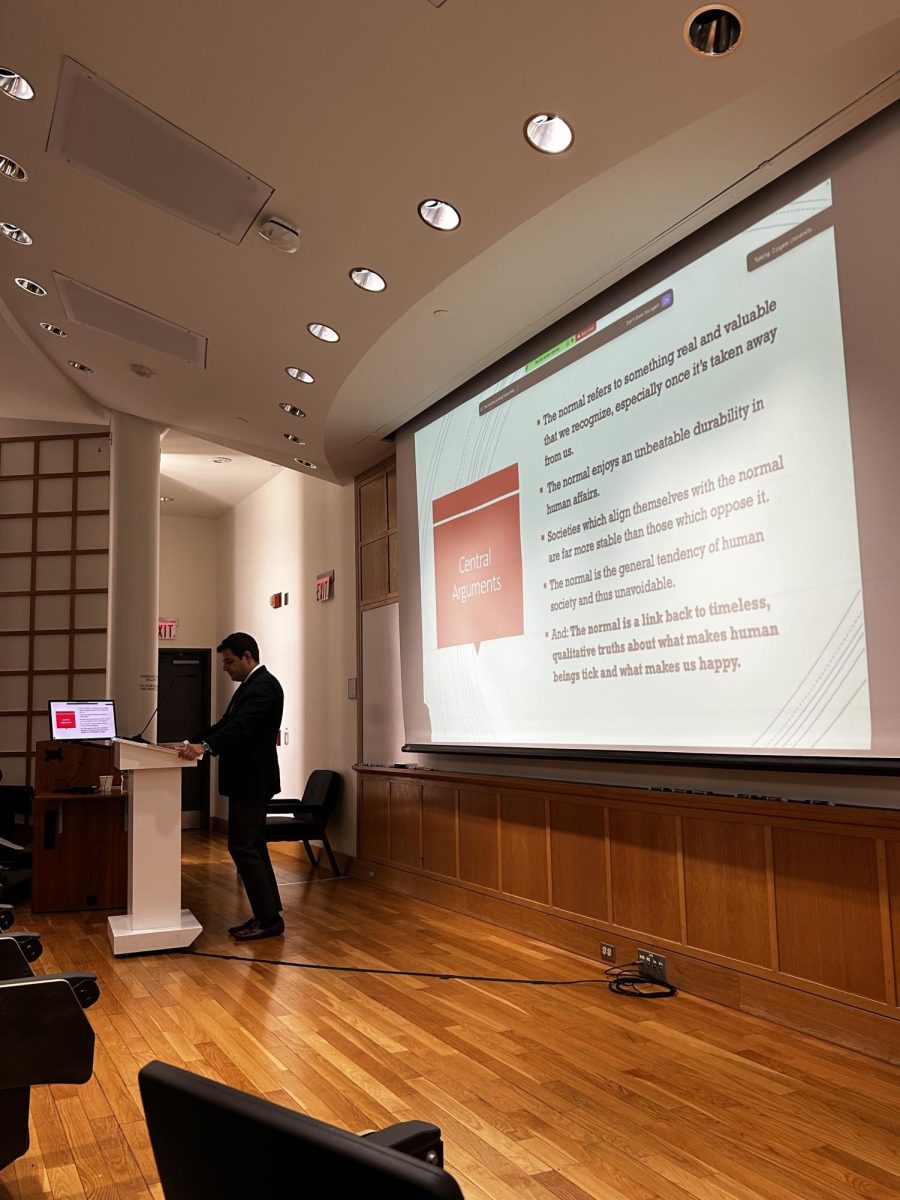

Fitzgerald’s novel sobers us with the living reincarnation of a Catholic father, railway and war bond fortunes, country clubs and prohibition, the attempted murder-suicide of a mare and her rider, and even the devil himself appearing to see the boy named after love. Death strikes unannounced and love fades the sins of prior nights on the minds of dreamers. God is put on trial and fails to appear before the court. For perhaps the first time in literary history, Fitzgerlad proposes: Is life really changing for the better, or is change made to rest our bodies unintentionally wearing down our souls?

Amory speaks with Eleanor upon her confession of atheism: “But I have to have a soul […] I can’t be rational – and I won’t be molecular.”

So I propose this novel to be read for the beauty of the irrational. You may find the narcissism and ignorance from Amory to be unpalatable, but look deeper and you will find yourself. Like Amory, we may refuse to give up, our convictions becoming our bread and butter, and we may slouch forward. Perhaps not towards Princeton (or Colgate University), but maybe towards love. That when we seek the unobtainable, in our barren souls we may incur the beautiful and find our place in this side of our strange Paradise.

Rating: 5/5