Through the launch of the Sputnik 1 satellite on Oct. 4, 1957, mankind reached into the cosmos with a hand gloved in steel and seized the stars with an ironclad grip that has hitherto endured. The satellite, designed by the Soviet Union, commenced humanity’s first dance with the aether.

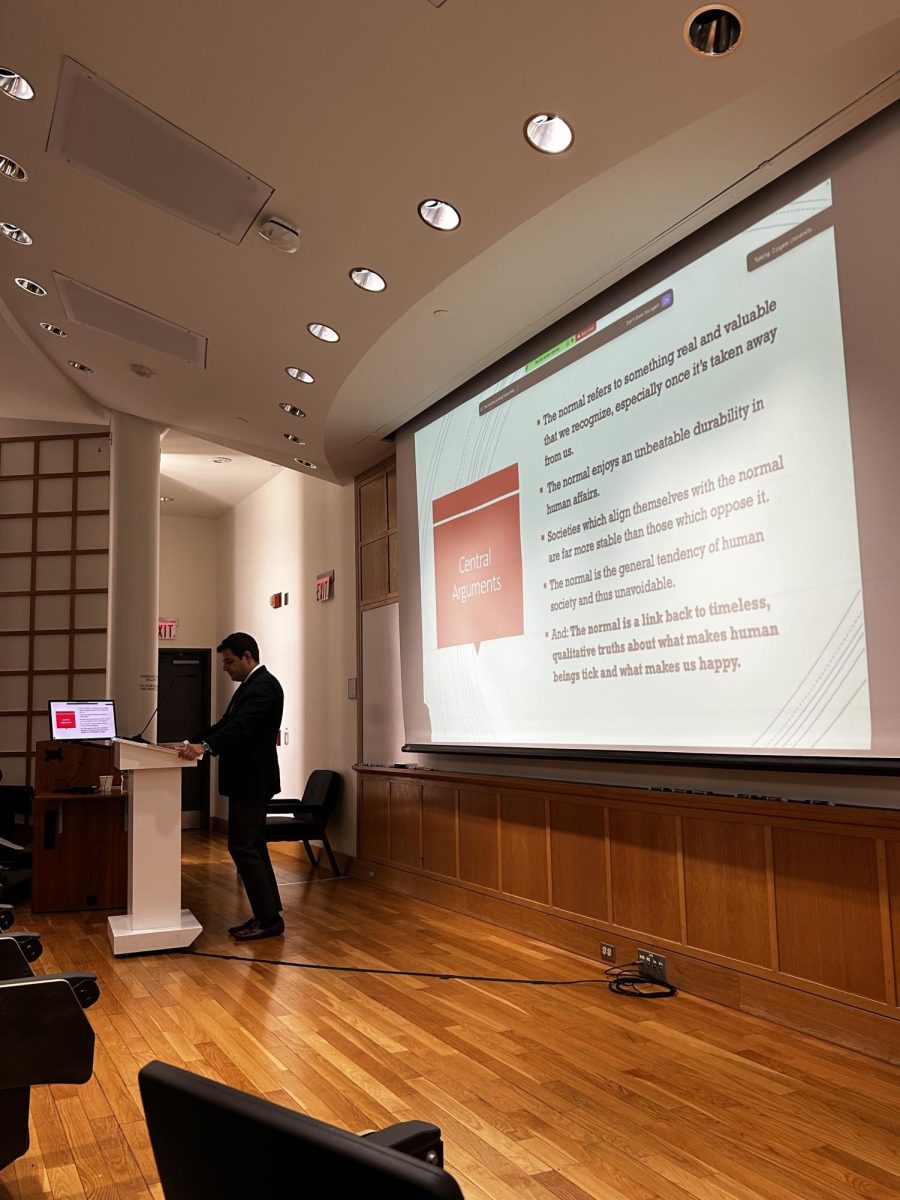

No more than a year later, the political theorist Hannah Arendt delivered a warning regarding mankind’s intrigue with technology in her seminal book, “The Human Condition.”

“[We], who are earth-bound creatures and have begun to act as though we were dwellers of the universe, will forever be unable to understand, that is, to think and speak about the things which nevertheless we are able to do,” Arendt wrote.

Humanity’s lust for scientific knowledge seems to outpace its understanding of it. That was during an era of space exploration and nuclear armament. Now, we live in a world of decentralized currency and artificial intelligence (AI).

Arendt’s fears of a human race surpassed by its technology have since been eclipsed by her contributions to the field of political science. I aim to repurpose and revitalize those fears in the modern context of humanity’s relationship with the environment. While Arendt’s concerns were perhaps more direct — the threat of unmanaged science in the nuclear age — the concerns of our present rest (or at least ought to rest) in the silent annihilation of our planet by technology.

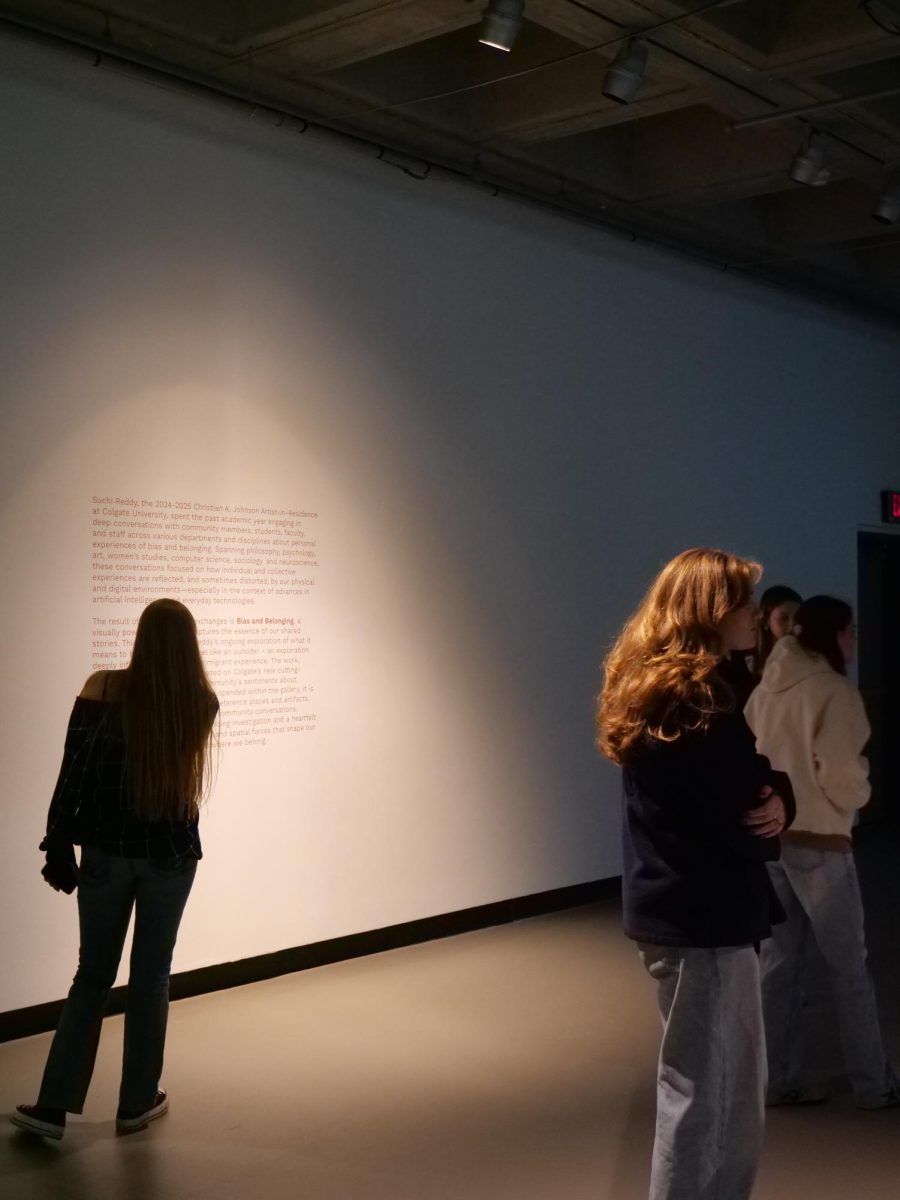

Environmental harm is the ugly truth that lies below the surface of our new technological achievements. This has been a constant theme in the history of our species, but, contemporaneously, it is most salient in blockchain technology and generative artificial intelligence.

According to researchers from the MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research (CEEPR), the annual electricity consumption of Bitcoin technology alone is 48.2 terawatts per hour, producing carbon dioxide emissions between 21.5 and 53.6 metric tons of CO2. For reference, this amount of carbon emissions “sits between the levels produced by the nations of Bolivia and Portugal,” according to CEEPR.

Research from the University of California, Riverside, states that the training process for artificial intelligence models like GPT-3 “can directly evaporate 700,000 liters of clean freshwater.” They predict that by 2027, AI models may globally account for between 4.2 to 6.6 billion cubic meters of water withdrawal.

These are a few figures which provide background to the environmental threat of new technology. But my point is less so with analyzing the facts and more with analyzing our treatment of those facts as a society. In the century of cutting-edge technology and ever-improving machines, we treat environmental harm as a necessary sacrifice for our mechanical achievements. We acknowledge the damage we do, but only idly — for our quest for a more technologically advanced society must be the perennial priority. There are costs along the way — to our environment and the communities directly affected by climate change, but we brush these off as marginal and ephemeral. Because what higher goal is there than technological progress? We seem unable to conceive of one.

In her book, Arendt imagined a future in which humans are genetically engineered, mechanically augmented and evolve to live far beyond one hundred years of age. She called this creation “the future man.”

“This future man, whom the scientists tell us they will produce in no more than a hundred years, seems to be possessed by a rebellion against human existence as it has been given, a free gift from nowhere […] which he wishes to exchange, as it were, for something he has made himself,” Arendt writes.

This rebellion against nature cannot be sustained. In order for our progress to be environmentally viable, a reversal of our priorities is needed. We must not sacrifice our environment for the sake of progress, but progress for the sake of the environment. Nature must not be seen as a means but as an end.

Perhaps it is too early to say that we are that future species. Perhaps we are not yet in a rebellion with our existential being and have not yet opened some mechanical Pandora’s box before us. But, clearly, we show no signs of stopping our pursuit of a computational society. The horizon we race towards seems no closer than before. Thus, like the launching of Sputnik 1 into the sky, we plunge further into a titanium void, biting the costs we delegate to the Earth.