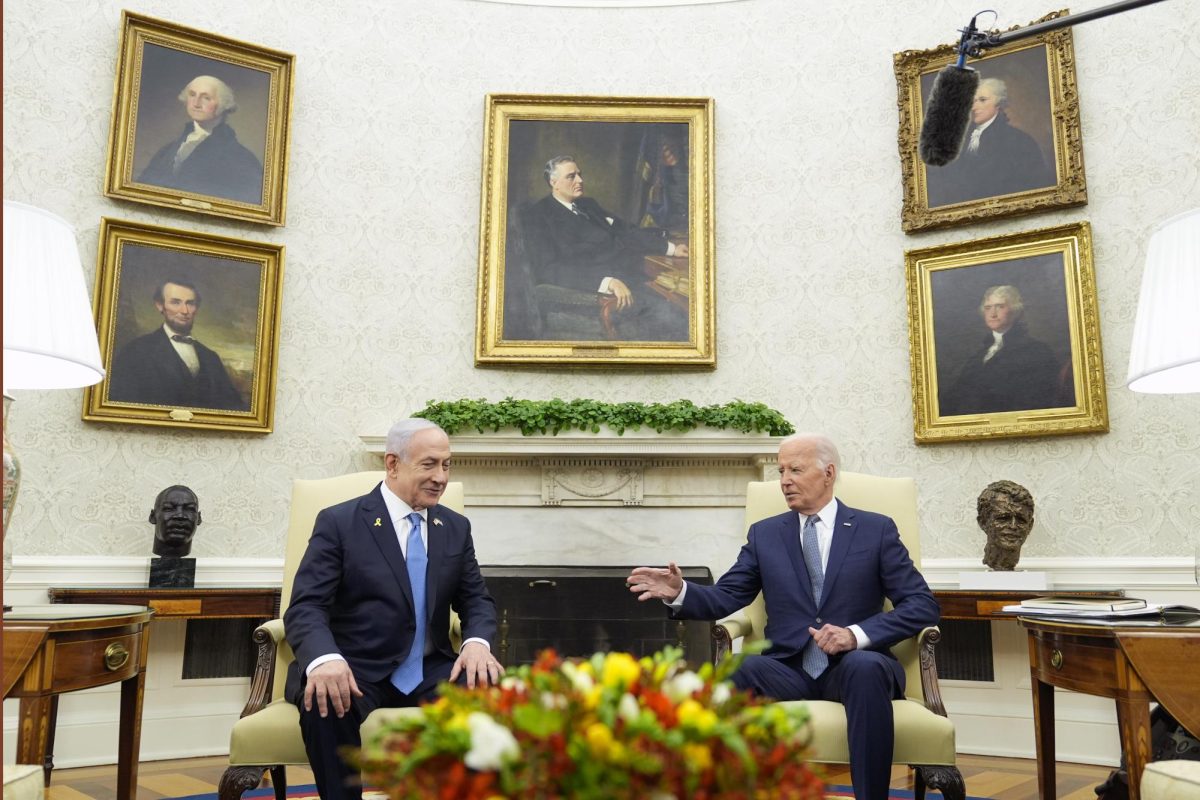

On Jan. 2, Claudine Gay resigned as president of Harvard University in response to mounting evidence of plagiarism in her academic work and her response to campus anti-semitism in the aftermath of the Oct. 7 Hamas attack on Israel. I found the resignation welcome: A plagiarist has no business running America’s most storied academic institution, and Gay’s inability to quell campus turmoil betrayed a fundamental lack of leadership. But it would be a mistake to think that her ouster means a battle has been won. The Claudine Gay saga should merely be the opening bell in the fight to reclaim our universities from the toxic ideology of intersectionality and victimhood that has captured them over the last decade.

Gay’s troubles stemmed from a Dec. 5 hearing of the House Committee on Education and the Workforce, where she testified that a call for the genocide of Jews would not, in most instances, violate Harvard campus policy. It might have been an acceptable response if Harvard demonstrated an equal commitment to broad free speech rights for all students and faculty — indeed, in many cases, such speech would be protected by the First Amendment at a public university. Yet Harvard’s commitment to that cause is suspect: The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), a free speech watchdog, ranks Harvard dead last among American universities for freedom of expression on campus. Specific failures to protect unpopular points of view illuminate FIRE’s ranking. Take, for example, Professor Carole Hooven, who recounted her Harvard experience in a recent essay for The Free Press. A renowned evolutionary biologist, Hooven resigned under pressure from Harvard in 2021 after boldly claiming that there is a biological difference between males and females. Rep. Tim Walberg highlighted this bizarre juxtaposition at the Dec. 5 hearing: A call for Jewish genocide violates Harvard policy only under narrow circumstances, while a biologist’s statement of a simple biological fact is a grievous offense. The upshot is clear: free speech, but only for favored causes.

That only tells half of the story, though. There is a more important question to be asked: How did support for Hamas become this sort of favored cause? The strange and shocking split-screen highlighted by Rep. Walberg has deeper roots: It is the highest-profile example to date of the intersectional ideology that has captured elite college campuses over the past decade. As an academic matter, intersectionality is not all that objectionable. It represents the idea that a person’s various identities might interact to produce privilege or disadvantage. But while it might be helpful in small doses, I feel intersectionality has swallowed many elite American campuses whole. As University of Florida president and former U.S. Senator Ben Sasse recently explained in The Atlantic, it has evolved into a rigidly inflexible doctrine where every conflict or debate in life must be made to fit neatly into the frame of oppressor versus oppressed. And the oppressed are right, no matter what. Ex-President Gay had worked in — indeed, had helped to build — this campus environment for most of her career. Her disastrous response on Dec. 5 can simply be seen as the culmination of that project. Intersectional thinkers suffer from a basic lack of moral clarity: In the endless quest to separate the world into good and bad, they ultimately lose the ability to evaluate right and wrong. The apparent campus impulse to lionize Hamas appears to be the clearest reflection of that reality. Hamas’ lack of relative ‘privilege’ makes them the ‘good guys,’ and therefore excuses their genocidal intent.

Understanding the Claudine Gay debacle in light of the broader fight for our campuses clarifies that her ouster is not — and cannot — be an isolated incident. Instead, it must be the opening salvo in an effort to rescue our college campuses from the unthinking and uncritical mode of cognition that has overtaken them. There is reason for hope: The episode has demonstrated that there are real consequences for academics and leaders who embrace a mindless notion of intersectionality. The ideology’s inability to perceive nuance does not survive prolonged contact with the world outside of the campus bubble. And its dulling of adherents’ moral compasses might ultimately set them on a collision course with a basic human instinct: that of right and wrong. As the broader public begins to see the consequences of intellectual rot at our most treasured universities, they are likely to demand change.

Another reason for hope is more personal. My experience at Colgate University has not been the one described by students and faculty at other elite institutions. In three-and-a-half years of writing conservative political opinions here, I have not once been muzzled, either formally or informally. In three-and-a-half years of expressing conservative points of view in class, professors and students have engaged with my ideas thoughtfully and respectfully — only a couple of dirty glances have come my way. I don’t claim to know why Colgate has more successfully resisted the intersectional fad than other schools of our ilk. But our experience serves as a heartening reminder that even in today’s intensely polarized age, it is still possible to debate, discuss and agree to disagree in the quest for a deeper understanding of ourselves and our world.

Andrew Rubin • Apr 26, 2024 at 7:11 pm

Thanks for sharing. A curious alum.