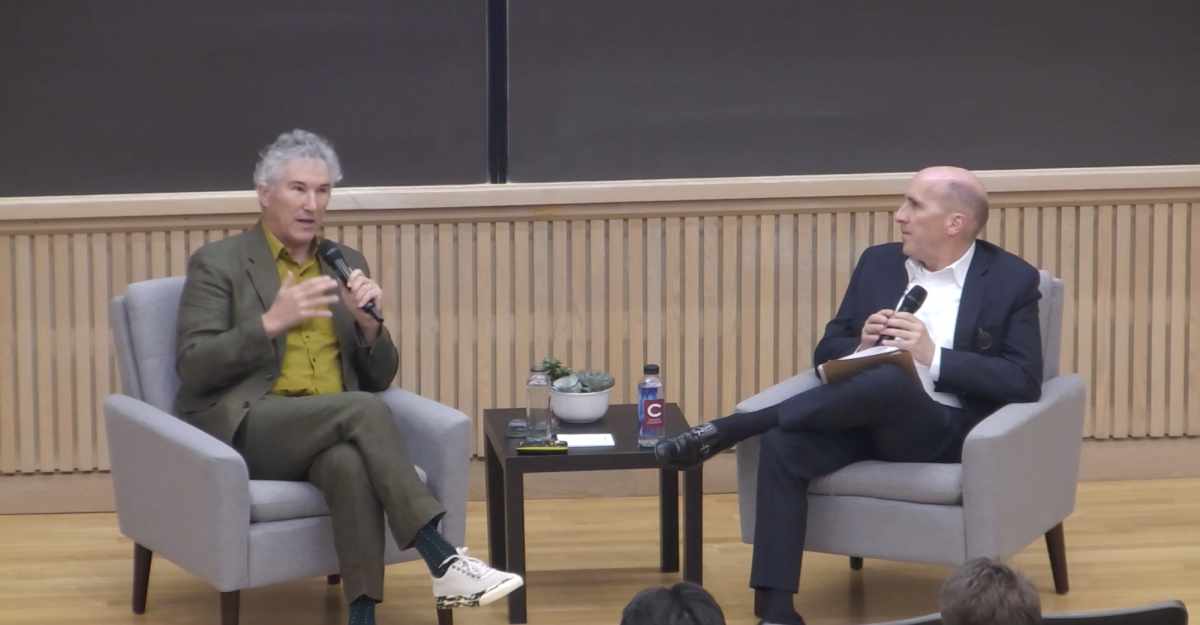

In honor of Valentine’s Day and the $2 billion a year that Americans spend on chocolates for the holiday, the NASC Colloquium series hosted a lecture titled ‘The Science of Chocolate” on Friday, Feb. 16. Led by Assistant Professor of Biology Priscilla Van Wynsberghe, the panel brought together professors from a variety of Colgate University natural sciences departments to discuss the intricacies of chocolate and how it came to be the sweet treat of today.

Van Wynsberghe offered insight into the origin of the lecture and how working in close proximity with Associate Professor of Biology and Neuroscience Jason Meyers inspired the conversation.

“This is a story that came to be because of the Olin Hall renovation, which means that we are stuck in weird lab places and we are hanging out with people that we don’t always hang out with,” Van Wynsberghe said. “Professor [Meyers] and I happened to be sharing a lab space while [Olin] is undergoing renovation and, as you are when you sit around doing your experiments, waiting for things to happen, you talk about things. Somehow we started talking about chocolate and then we started talking about the science behind chocolate.”

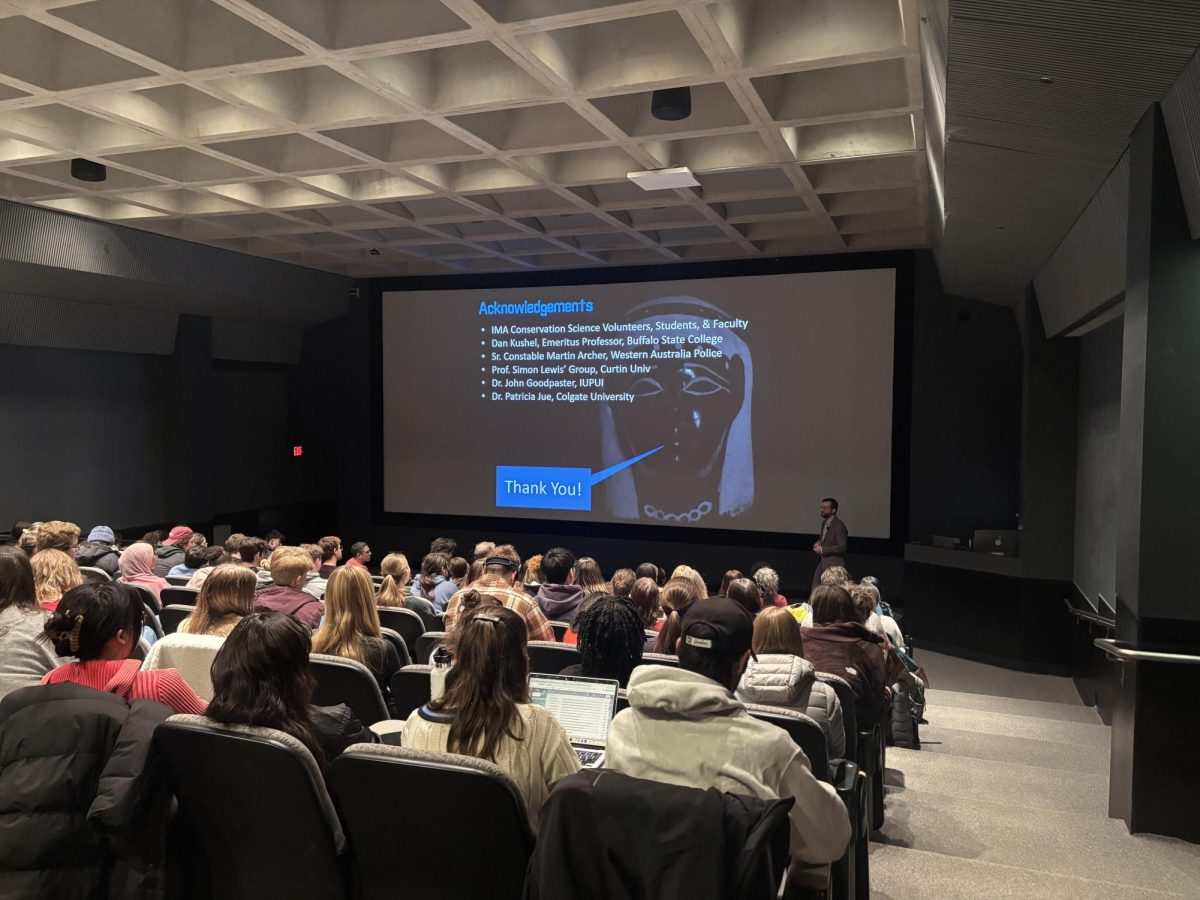

The panel, which brought an audience that filled the lecture hall in the Ho Science Center, also featured a tasting element, where participants sampled chocolates from Hershey, Dove and Ghirardelli. Professor of Biology and Environmental Studies Frank Frey also held a show-and-tell portion, where he passed around cacao pods and explained cacao farming practices, which rely on a species of insect called the biting midge to fertilize the flowers.

“If you count up the number of flowers an individual [cacao] tree makes in the rainforest, about 10 percent of those flowers will turn into fruits,” Frey said. “Thousands of flowers can [make] hundreds of fruits, if you’re in the rainforest. As Nestlé and others learned, when you take those trees out of the rainforest and put them in wide-open spaces — no rainforest, no leaf litter — to try to have mechanical cultivation of trees, [biting midges] don’t live there, so only about 0.2 percent of those flowers turn into fruit.”

Sophomore Theo Freeman enjoyed learning about the farming practices and was especially interested in this statistic.

“It surprised me that only 0.2 percent of flowers turn to cacao fruits in a farm setting,” Freeman said. “It was also cool seeing the inside of the cacao fruit.”

After discussing the cacao fruit, the panel dove into the specifics of different chocolate manufacturing processes.

“Cacao seeds are [around] 55 percent fat,” Frey said. “How do we get the chocolate that you eat? We recombine together different ratios of cocoa powder, cocoa butter, milk, vanilla, sugar and other things to make the chocolate. That’s where chocolate comes from.”

In terms of chocolate production, Van Wynsberghe also discussed how milk chocolate and dark chocolate differ, before allowing the audience to sample them.

“In addition to the cocoa butter and the cocoa powder that we were talking about, they’re adding milk and lots of sugar, so that’s why we call it milk chocolate. That’s different from the dark chocolate,” Van Wynsberghe said. “Dark chocolate [has] a whole range of types, but the main thing that makes them similar is that they do not have milk in them. They can contain sugar, but there’s going to be varying amounts of sugar. That percentage that you read […] refers to how much cocoa versus how much sugar is in them.”

Van Wynsberghe also revealed the hidden truth of white chocolate.

“White chocolate, in some ways, is kind of a misnomer. It doesn’t have that cocoa, so it doesn’t have that bitterness associated with it,” Van Wynsberghe said.

While the professors examined chocolate from a biological perspective as well as its chemical and physical properties, Assistant Professor of Chemistry Jake Goldberg took a different scientific angle.

“I teach a CORE class in poison,” Goldberg said. “It turns out that chocolates are pretty terrible poisons for people. If you’re going to try to poison someone with chocolate, it’s not a good move. But if you were, the compound in chocolate that’s probably the most poisonous is caffeine.”

Freeman appreciated the multifaceted approach this NASC colloquium took.

“I thought the most interesting part was learning from the lens of so many different professors,” Freeman said.

The NASC Colloquium series will continue throughout the Spring 2024 semester, covering a wide range of topics that aim to incite similar levels of enthusiasm for science.