The Colgate University Russian and Eurasian Studies Department (REST) held a discussion event on Tuesday, Feb. 20, on the recent death of Russian opposition leader and dissident political activist Alexei Navalny. The event revived their long-standing REST Think Tank program that was suspended during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Associate Professor of Russian and Eurasian Studies and Director of the Russian and Eurasian Studies Program Mieka Erley organized the event in concert with the REST Department in the wake of Navalny’s death, which took place in a Siberian penal colony on Thursday, Feb. 16. According to Professor Erley’s introduction, Navalny was a political prisoner targeted by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s regime for his pro-democracy activism and anti-regime opposition efforts. The Russian regime was widely believed by the West to have been responsible for Navalny’s death, which accordingly had tremendous ramifications for the future of Russia.

“This was a serious event that needed to be addressed by our department,” Erley said. “We needed to respond to the gravity of the situation in a timely way.”

Professor Erley began the lively discussion by showing guests a video address posted to Navalny’s popular YouTube channel, in which his widow Yulia Navalnaya pinned her late husband’s death on Putin, vowed to continue his activist work and urged others around the world to take up his fight, as well.

Assistant Professor of Political Science Masha Hedberg explained to the room that she nonetheless did not expect Navalny’s death to trigger a powerful anti-regime response in Russia.

“Some major political movement as a response to this is truly aspirational — and that’s not to say it doesn’t have any effect. I think people will remember this; I think this is another thing that you begin to associate with the current regime, and if you have enough of these really terrible associations, some effects will be forthcoming,” Hedberg said. “I don’t see this as the catalyst.”

On the other hand, Assistant Professor of German Irina Kogan pointed out the importance of individual expressions of protest in Russia, like creating ad hoc memorials to Navalny or placing flowers on a monument to political repression in Moscow. Since these actions are punishable by the Russian state, they are risky and dangerous. Professor Kogan hence found that these minor though courageous acts powerfully underscored Navalny’s impact and legacy in their own way.

Associate Professor of Linguistics Emeritus Alexander Nakhimovsky expressed deep admiration for Navalny. While he believed that Navalny was one of only three people who Putin ever found dangerous to his regime, he characterized Navalny’s overall historical impact as negligible.

“Navalny was different, and in any minimally normal country, he would be president. He had the talent [and] conviction; when he spoke extemporaneously in focused sentences and paragraphs, they were brilliant,” Nakhimovsky said. “I miss his presence, personally. Of course, in major political terms, he is a minor footnote in Russian history.”

Conversely, senior Alec Bresler felt that Navalny was significant because he represented the possibility of change in Russia, disrupting the narrative that Russians have a mentality that is inherently incompatible with democracy.

“What we should call out is rhetoric having to do with Russia — or people in any country — saying these people’s culture is so backwards, and they’ve been living under dictatorship and authoritarianism for so long that they’ve just become this country that can’t live with western values,” Bresler said. “It’s not true. It’s going to take a lot of work, but I don’t think it’s true.”

Discussion participants moved on to considering a fundamental issue in Russian politics: the difficulty of building a strong political opposition movement in Russia, as Navalny had dedicated his life to achieving. Professor Hedberg blamed an apathetic population, the allure of a charismatic figure like Putin and the internal divisions within opposition movements.

“There are so many different strains of opposition that disagree with each other in terms of very fundamental values. So if you ever wonder, ‘Why is it so hard to create an opposition movement in Russia?’, these are all the fundamental reasons,” Hedberg said.

Professor Nakhimovsky characterized the current regime’s authoritarian control and powerful propaganda as the root of the issue.

“The power of Putin’s oppression is overwhelming, and Putin is very smart; he knows how to organize oppression and how to make it appealing to the people of Russia,” Nakhimovsky said.

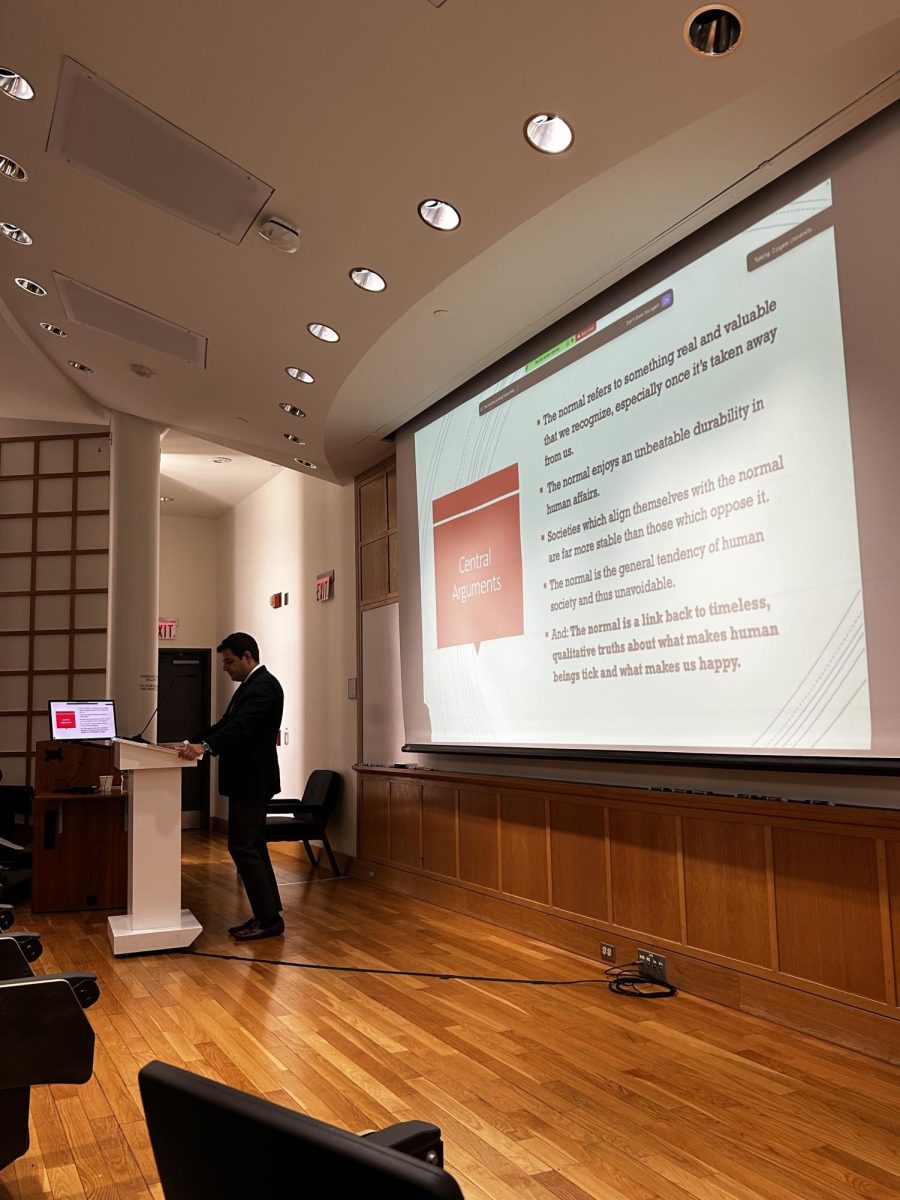

The event notably took the form of an egalitarian discussion between professors and students instead of a regimented lecture. Professor Erley noted that she felt this discursive approach to learning to be valuable.

“Ideally, students would have a chance to ask questions and get honest answers back, not in the format of this top-down model [where] the instructor gives you a set of facts or tells you how to interpret or understand something,” Erley said. “It’s [meant to be] much more horizontal, [where] different faculty members in conversation with each other disagree about things.”

This discussion format produced a conversation that was broad in scope and touched on diverse aspects of the Navalny discourse. Director of LGBTQ+ Initiatives Lyosha Gorshkov was able to point out that Navalny was a complex political figure who had expressed homophobic and xenophobic sentiments in the past, and that his victimhood could lead to a warped view of his legacy. Gorshkov also warned generally against idolizing figures like Navalny.

“Honestly, I don’t want Navalny to be dignified in martyrdom,” Gorshkov said. “I don’t have idols because I think that’s a big problem. When we put weight in one person, we miss the mark.”

Visiting Assistant Professor in University Studies Aleksandr Sklyar brought the conversation back to Navalnaya’s compelling video address, connecting the event discussion to the ongoing Russian war against Ukraine.

“How many hundreds of thousands — millions — of Ukrainian women have been through what [Navalnaya] is describing? How many people have been on the other end of having lost their family, their brothers, their cousins, their husbands to Russia’s aggression, to Russia’s political murders, whether they’re in wartime or otherwise?” Sklyar asked. “I don’t know how much sympathy I necessarily have for what she’s going through, [whether it’s] more valid in some way than women who have lost not only their husbands and so much more, but their homes, their country or their family more broadly to Putin’s Russia.”

Professor Erley indicated the likely possibility of future events like this one. Prior to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the REST department held discussions as part of their Think Tank series on most Tuesdays during the free midday lunch period. The Navalny discussion event signaled the resurgence of this department program.

“We have these informal conversations that would bring together faculty, students [and] anybody who wanted to come — sometimes members of the community come — just to have this kind of open space for people to ask questions and have conversations about things that are happening in Russia,” Erley said. “We’re bringing it back.”

Ultimately, Professor Erley found that this event and future REST Think Tank programming are significant for the entire Colgate community, as their importance transcends the REST department itself.

“It’s an election year in Russia and in the [United States], and we’re dealing with some of the same political problems: that increasingly our political landscape looks like Russia’s political landscape, and that they are also deeply intertwined,” Erley said. “That’s why Americans need to care about what’s happening in Russia.”