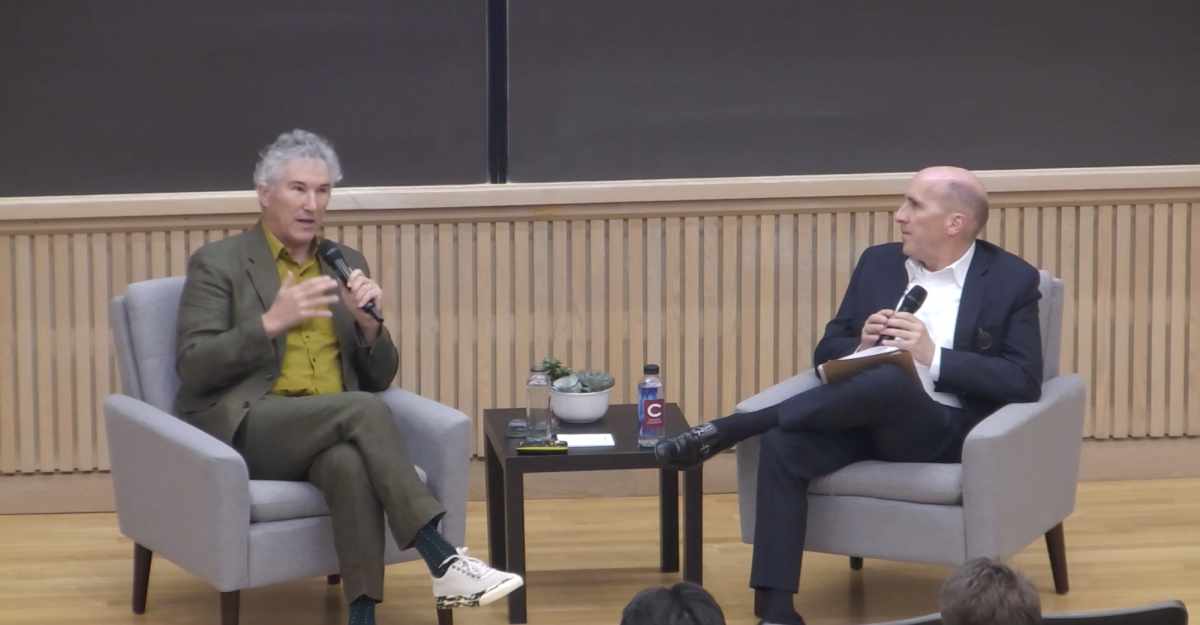

The Department of Sociology and Anthropology hosted CJ Pascoe, professor of sociology at Oregon University and award-winning researcher of inequality in schooling, on March 19 for a brown bag discussion on “Girl Boss Feminism and Mundane Misogyny.” Pascoe presented on the limitations of kindness in solving systemic injustice through the lens of her case study of an Oregon high school, to which she gave the pseudonym ‘American High School.’

Pascoe began the lecture by discussing the recent popularization of kindness as a mantra and trend. While ordinary people and experts alike view kindness as a cure-all for social ills, Pascoe staunchly disagreed. The issue, as Pascoe laid out, arises when reactions to inequality are limited to alleged cure-alls like kindness, making systemic inequalities inaccurately seem like individual problems that don’t require fundamental shifts in society.

“Healing has to be about equity and justice, not just feelings. There is no indication that lack of kindness is the reason why black men and women are more likely to be killed by racist police violence than white folks are,” Pascoe said.

Pascoe introduced her recently published book, “Nice is not Enough: Inequality and the Limits of Kindness at American High,” which chronicled her two years spent studying the students, faculty and culture at a school whose mantra is kindness. According to Pascoe, American High is full of accepting people and littered with exhortations of kindness. It is a place where cheerleaders fill bathroom mirrors with uplifting messages and students form clubs dedicated to spreading positivity.

But that overwhelming kindness has limits, Pascoe argued — limits that became clear when students took a stand against systemic racism, when faculty demanded safer schools and inclusive mental health care and when young girls grappled with gender inequalities and harassment. This student and faculty activism was put down by the administration because it was deemed too political.

“Political talk is off limits at American High. So, what fills in for it? A language of kindness and acceptance,” Pascoe said. “Rather than thinking of inequality as something built into our institutions, schools or religious, political or economic institutions, we consider them individual issues. Avoiding political topics and replacing them with kindness is a way we develop individual solutions to systemic problems.”

This “sugarcoating,” as Pascoe called it, frames systemic inequalities as a matter of offense or opinion rather than an issue of exclusion, power or domination. Pascoe recalled a student assembly celebrating black history and excellence amongst leaders and activists from the Civil Rights Movement. As the assembly began, a group of students wearing ‘Make America Great Again’ hats filed into the front row. Students in the school’s Black Student Union and Latinos Unidos shared feelings of shock, dismay and anger with Pascoe, but the administration remained silent. Instances like these are examples of benign diversity, which Pascoe argues positions diversity as a cultural value, but fails to link it to inequality.

“Diversity becomes less about purposeful inclusion of historically excluded groups of folks and becomes quite simply a celebration or at least tolerance of any kind of difference, […] whether or not that difference has anything to do with inequality,” Pascoe said. “You can see this leads to a solution of things like love and acceptance, rather than justice or equity. The regime of kindness characterizes American High, from signs denouncing hate to interpersonal niceness to those positive messages on the bathroom mirror.”

An American High School Black Lives Matter (BLM) exhibition brought up the same patterns of silencing and performative activism. After facing much administrative pushback on organizing a Black Lives Matter event in the wake of George Floyd’s death, students and faculty managed to get their idea passed, but not without conditions: the administration required that the ‘police perspective’ be included in the gallery, pushed it into after-school hours as to avoid compulsory attendance by ‘uncomfortable’ students and framed it as a healing circle rather than a protest or memorial. Following the event, the message wall was filled with notes like “Please be kind to each other” and “Why can’t we all just love each other?”

Pascoe unpacked the harm in this approach.

“The board read ‘kindness matters’ as if kindness or love are the actual factors behind systemic police violence. Not, say, a legacy of racial inequality embedded in institutions, organizations and belief systems,” Pascoe said.

First-year Cooper Thompson felt moved by this particular segment in Pascoe’s lecture.

“The BLM message wall Professor Pascoe showed us really struck me. Under this ‘kindness regime,’ as she put it, institutionalized racism becomes distorted to center on white people being careful not to hurt people’s feelings rather than the real issue, which is the privilege white people are afforded by a racist system they created. The story of American High suggests ways we might begin to center a politics of care instead of kindness,” Thompson said.

Pascoe moved on to discuss how homophobia and sexism pervade the structures and systems of American High. Despite zero reports of bullying or harassment from LGBTQIA+ students at American High, members of the Gay Student Association shared many grievances with Pascoe. The problems were not interactional but institutional: the lack of queer celebration and ritual at the school, the inaccessibility of gender-inclusive bathrooms on campus and the underrepresentation of nonbinary people in the faculty. Institutional sexism emerged similarly. According to Pascoe, the “girl boss” feminism available to high school-age female-identifying students perpetuates cyclical harassment.

“[It’s] a feminism that’s not about challenging gender inequalities, but it’s about being individually empowered to navigate the unchanging sexism and the type of harassment that these girls experience every day,” Pascoe said.

American High puts the onus on these female-identifying students to respond to and prevent the digital harassment, catcalling and sexism they deal with every day.

“In the same training where they’re told to watch what happens on their cell phones, the principal tells the girls that the slogan ‘your body, your choice’ means not that you have the right to self-determination in the face of state repression, which is what the slogan actually means, but that you have the responsibility to have an exit plan in a sexually unsafe situation. Sexual violence is sugarcoated in a way that leaves girls without a language to talk about this behavior,” Pascoe said. “Even when girls do stand up to this sort of harassment, they’re still constrained by the same sort of kindness and niceness culture that permeates the school in the first place.”

First-year London Pettibone recognized this form of benevolent sexism that simultaneously praises and patronizes women.

“The anecdotes Pascoe shared with us from girls at American High sound eerily familiar,” Pettibone said. “I definitely feel like I am overly-cautious about how nice I come off, and guilt about ‘causing a stir’ has made me bite my tongue in situations I know I had the right to speak up about. Like Pascoe was saying, that mindset has to be unlearned on the individual and institutional level.”

In the face of the limitations of kindness so clearly exemplified at American High, Pascoe offered a potential solution: replace the politics of kindness with the politics of care.

“Politics of care is an approach to power and resource distribution and public morality that centers human needs, vulnerabilities and systemic disparities. It addresses the structural roots of problems rather than relying on these feel-good individual responses,” Pascoe said.

She outlined her solution into three parts: systematizing care, moving away from securitized responses and conducting an audit of campus life.

“First, we have to systematize care. We have to build it into our institutions the same way we build in things like inequality,” Pascoe said. “Second, we need to move away from securitized responses in student safety. We need to focus as much on incorporating marginalized students into the life of the school as we do with protecting them from things like bullying. This means we need to move away from punitive responses, like tip lines routed through state police. Rather than the securitized responses, we need to institute more restorative justice processes which focus on repairing harm rather than compounding inequalities […]. Finally, they need to do an audit of our schools’s social life.”

Pascoe saw American High as a microcosm of trends in school culture on the national level. According to her study, even though bans on lessons about racism and policies targeting trans youth are not yet directly impacting the students of American High, those policies are animated by logic similar to that which shapes American High and draws limitations on what is ‘appropriate’ for the classroom.

Pascoe saw high schools as an essential place to target these inequalities and start reshaping young minds under the politics of care.

“Schools are not a singular solution to inequality, but they are where we produce our future citizens. We need to prepare young people for citizenship by equipping them with robust language to discuss the experiences, causes and consequences of systemic inequality,” Pascoe said. “When political talk and action are banned, it leaves a void that gets filled with a regime of kindness.”

If we can make inequality systemic, Pascoe argued, we can also make equality systemic.