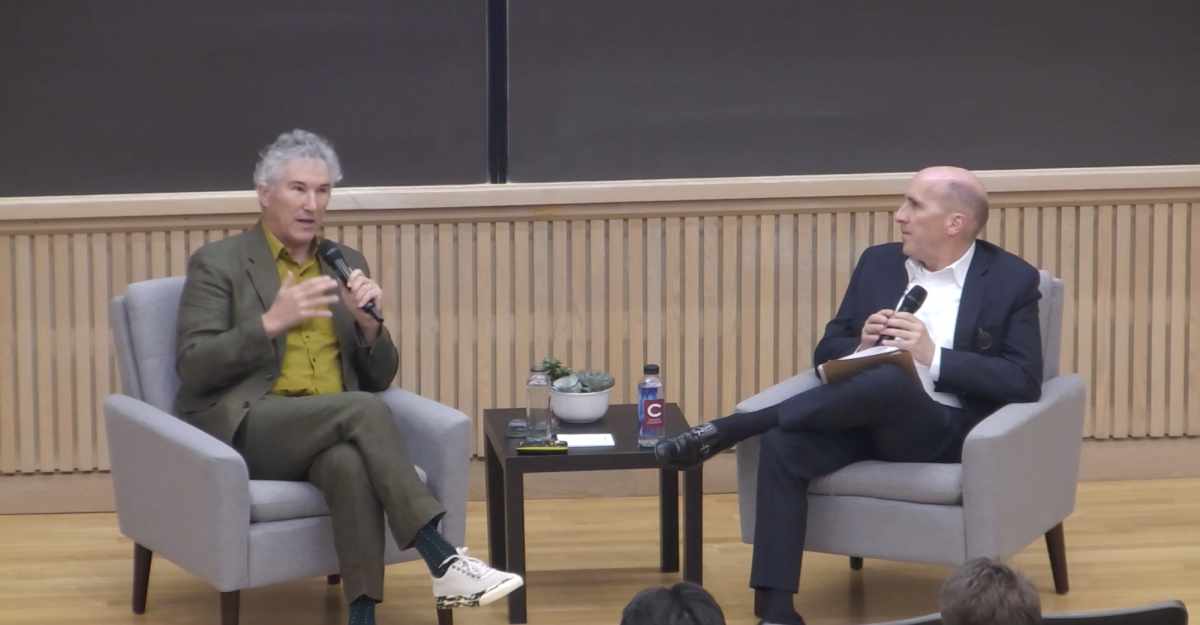

The Lampert Institute for Civic and Global Affairs hosted David E. Sanger, a three-time Pulitzer Prize winner and professor of national security at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, on March 26. Sanger discussed his upcoming book, “New Cold Wars,” which will be released on April 16.

Sanger’s 40 years of experience as a White House and national security correspondent at The New York Times equipped him with a wealth of intimate knowledge of national security, diplomacy, cyber conflict and geopolitics. The writer told attendees how the introductions of cybersecurity and cyberwarfare have irreversibly changed the fabric of our diplomacy with Russia and China, two countries whose technological capabilities produce real threats to the United States.

Sanger’s speech, interwoven with anecdotes from his years as a journalist, spoke critically of how foreign policy officials have failed to accurately predict and respond to global events. He discussed how, for a long time, Americans were disillusioned by the idea that we had left the era of nuclear peril behind on the headstones of the Cold War. As detailed in “New Cold Wars,” the Russia-Ukraine War completely changed how Sanger thought about this era.

“We deluded ourselves into thinking that the entire era of superpower conflict was over. We thought a permanent era of peace had descended among world superpowers, that democracy had emerged victorious [and] that at the end of the day, the world’s biggest nations would come to the conclusion that they had to base themselves on American law,” Sanger said.

Sanger spoke extensively on the lead-up to the Russian invasion of Ukrainian territory on Feb. 24, 2022. Sanger was regretful about the lack of proactivity by NATO member state governments.

“I argue that this intelligence failure was the biggest thing we missed in my professional life, and it wasn’t just the U.S. government,” Sanger said. “We missed it, the Europeans missed it and reporters bought into it.”

Sanger recalled Putin’s 2014 address at the Munich Security Conference, in which he urged the restoration of Peter the Great’s Imperial Russia.

“That should have been the first big warning to all of us as to where Russia was heading. Seven years later, Putin grabbed Crimea. In 2018, the Germans signed on to Nord Stream 2 [a natural gas pipeline agreement]. From Putin’s perspective, he must have thought it was all so easy,” Sanger said.

The next few years oversaw a resurgence of nuclear force and a series of Russian cyber operations in the United States. According to Sanger, this worked well for Russia because the U.S. failed to see cyberattacks as the severe threat that they are.

“When the U.S. discovered Russia had stolen data from classified and unclassified systems, they wouldn’t even name Russia as the perpetrator. They blew it off in order to avoid escalated conflict over data theft,” Sanger said.

Sanger argued that this lack of deterrence by U.S. counterintelligence encouraged Russia to heighten its operations. They began to put code inside critical infrastructure such as power grids, water systems and financial systems.

By May of 2021, a Russian attack on Ukraine seemed imminent. After satellites confirmed the location of Russian troops on the Ukrainian border, the futile U.S. strategy was to selectively leak news of the encroaching Russian troops to the public.

“The U.S. did everything they could to warn the world that this was coming, and still they didn’t believe. They still thought Putin was bluffing,” Sanger said.

He recalled the surreality of the days leading up to the attack.

“The Saturday before the war broke out, I sat down and had breakfast with Secretary of State [Antony] Blinken, and we spent the first part of breakfast comparing lists of people who had told us this wasn’t going to happen. That was Saturday. War broke out that Thursday,” Sanger said.

Sanger further discussed the international imperial implications of the American response to the Russia-Ukraine War. Using Taiwan and China’s relationship as an example, he spoke about Taiwan — a country that produces 90 percent of the world’s advanced microchips — and its geopolitical value in the U.S.

“What if China is now watching the U.S. start to shore up on their military and humanitarian aid and thinking, ‘if the U.S. won’t help Ukraine for more than 18 months, what will they do for Taiwan?’ […] If China invades Taiwan and wipes out the semiconductor plant, you better hope you don’t break your iPhone,” Sanger said.

President Biden’s answer to this economic dependency is to move some semiconductor manufacturing to U.S. soil, but Sanger explained the inadequacy of this solution. He believes a sufficient solution would require a more permanent shift of our economic priorities and the further implementation of industrial policy programs, a highly contentious issue in Washington.

“Those plants would only cover about four to five percent of the supply problem. Our solution is wildly insufficient to the dependency that we have built up. We have completely failed to rethink the dimensions of our national security,” Sanger said.

Professor of Economics Chad Sparber found Sanger’s convictions on America’s over-dependence on overseas manufacturing compelling, despite reservations about industry policy’s strangulation of outward-oriented markets.

“My instinct is to be skeptical of industrial policy. But given the national security concerns and the near monopoly on semiconductors, I’m willing to consider it here,” Sparber said.

Senior and Lampert Scholar Angela Mangione shared Sanger’s frustration concerning the contention around industrial policy within the U.S. government.

“I was surprised by David Sanger’s comments about how Congress avoids industrial policy, given that it would greatly enhance our national security position, especially our dependence on Taiwan’s semiconductors,” Mangione said.

Another problem, Sanger argued, lies in Washington’s improper prioritization of military artillery over economic bolstering.

“My personal opinion? We need those 10 [fabrication plants] much more than 10 new aircraft carriers that are sitting ducks for every drone out there,” Sanger said.

According to Sanger, these economic shifts create a dramatically different and more complex dynamic between counterposed powers.

“We have to fundamentally rethink the structure of our national security. In the old Cold War, we were not dependent on our adversaries for the products we use every day. We’re not going to live as easily without the products that we’re getting from China, or them without ours,” Sanger said.

Sanger’s concluding remarks stressed the uniqueness of this era of international diplomacy and the dangers of relying on history to repeat itself.

“If this is the era of new cold wars, I would argue that it is a more complex one than anything before. The old Cold War had a very long middle and a very surprising ending. If we are looking for this one to follow the same pattern to end with the collapse of our opponents and a clear victory for the West, we are likely to be sorely disappointed,” Sanger said. “There is no guarantee that these cold wars will stay cold.”

For Mangione, Sanger’s words prompted deep introspection.

“I have also been reflecting on the question he posed at the end: Why did we misjudge the past 30 years? For students, like myself, who are interested in pursuing jobs in the national security realm, it will be something that will be critical for us to understand as the next generation of policy makers,” Mangione said.