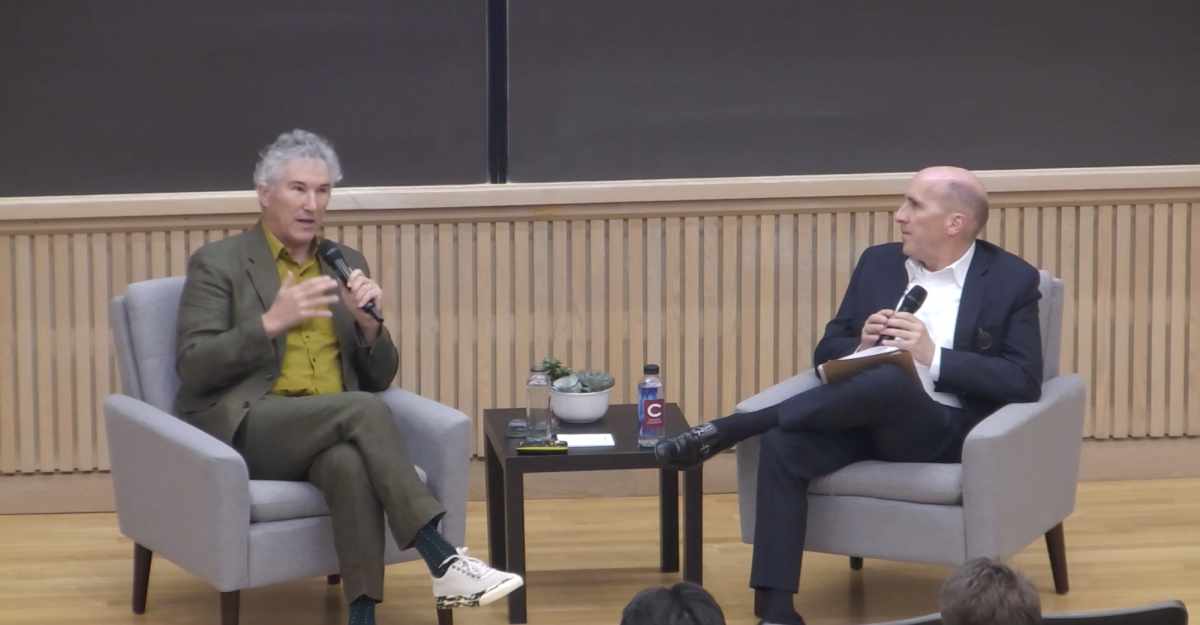

The Center for Freedom and Western Civilization hosted journalist Tony Connelly, the Europe editor for RTÉ, an Irish public service broadcaster, on Tuesday, April 9, as part of the Forum on Economic Freedom speaker series. Connelly’s lecture, “Brexit and Borders: The Northern Ireland Protocol,” provided attendees with an in-depth history of Brexit negotiations over the past eight years. The journalist’s lecture added nuance to the perspectives of the Irish, English and European Union (EU) on the matter and discussed the socio-economic and political implications of the United Kingdom’s (UK) withdrawal from the EU.

Connelly joined RTÉ as a radio and TV reporter in 1994, transitioned to Europe correspondent in 2001 and became Europe editor in 2011. Throughout his career, Connelly has been a journalist for the Irish Independent, United Press International and Time Magazine. He has also reported extensively on the Russo-Ukrainian War, the Israel-Hamas War and Brexit negotiations.

Connelly began his presentation by previewing the EU’s pre-Brexit economic framework, which was characterized by a single market economy with zero trade roadblocks, open borders and solid diplomatic relations. Britain joined the EU in 1973, the same year as Ireland. By joining, Connelly believes the vastly different countries established a strong and transformative relationship. The journalist spoke to pre-Brexit diplomacy between Ireland and Britain.

“Ireland and Britain, being part of the EU, meant that Irish ministers and British ministers met in Brussels, where Unionists would meet. Before Ireland and Britain joined the EU, there had been no meeting between an Irish prime minister and a British prime minister. It all added to a sense of growing confidence and friendship between Ireland and Britain within the European framework,” Connelly said.

However, disaffection began to grow among “Euroskeptics,” who felt that the EU restricted Britain’s sovereign power. Former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom David Cameron’s 2015 speech announcing the first Brexit referendum was the inception point of a turbulent eight-year-long road of political, economic and social negotiations. Connelly emphasized Britain’s motivations for exiting the UK, explaining that Ireland became central to Brexit taking effect.

Connelly continued by detailing a timeline of Brexit. First, there was a referendum held in June 2016, in which citizens voted to leave the EU, and consequently, an electoral bid for Conservative party leadership followed, in which politician Theresa May emerged victorious. The Brexit negotiation process came after this, with debates split into two sets of topics — divorce from the EU and mending the diplomatic relationship between the UK and the EU.

“Britain had to come out of the EU, unscramble 43 years of membership — ‘unscramble the omelet,’ as they call it — and then start a new relationship with the EU,” Connelly said. “It has damaged relations between Britain and the European Union, but more particularly, really damaged relations between Britain and Ireland, and set back the Irish people.”

First-year Lily Gamburg thought Connelly was well-versed in the challenge of deconstructing an immensely complex topic like Brexit into easily understood sound bites and articles. Gamburg spoke to Connelly’s ability to elucidate this hyper-complicated issue.

“I was very impressed by how eloquently and succinctly he broke down the timeline into digestible pieces. After hearing from him, I feel much more equipped to read and discuss the Brexit deals. It’s likely a credit to his experience in broadcast reporting that his talk was so engaging,” Gamburg said.

Connelly explained how Brexit posed a significant risk to Ireland, including how the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, established after The Troubles, a 30-year conflict in Northern Ireland, removed the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland to allow open trade. However, Connelly added that Brexit threatened the return of hard borders and strict patrol across the island, sowing the seeds of violence and civil unrest.

“For Northern Ireland’s Catholic Nationalists, the invisible border was vital to the Good Friday Agreement. If you start putting infrastructure on the border, there could be a tax, so therefore you need to have the infrastructure secured, which means you need police, and then the police might get attacked. Then you might have the army called in, and suddenly, you have the ingredients of a return to violence,” Connelly said.

Furthermore, Connelly described how Brexit’s economic borders imposed a distinction between northern and southern milk production in Ireland, disrupting the entire paradigm of dairy production upon which Ireland’s economy was heavily dependent. According to Connelly, the Brexit negotiations were riddled with contradicting promises, paradoxical clauses and a fatal lack of inter-governmental communication between EU member states.

The journalist recalled breaking a story in December 2017 announcing Britain’s concession that Northern Ireland would remain in the EU customs union before even former UK Prime Minister May knew about it. From this joint report emerged a treaty in which Britain outlined Ireland’s three “no hard border” options: a close trade agreement, an alternative agreement involving high-tech surveillance and border control or the “backstop” resort, under which Northern Ireland remained in the single market and customs union. The report signaled progress, according to Connelly, but May ultimately rejected it.

On the one hand, Connelly reported that May promised no hard borders. On the other hand, May told her party that Britain was unequivocally leaving the single market. Contradictions like this one, according to Connelly, slowed progress and oversaw rapid turnover in the British government.

First-year Micah Spicer attended the event and commented on the significant nature of the border question.

“I found the impacts of a hard border between Northern Ireland and the rest of Ireland extremely interesting. I wasn’t aware of the detrimental consequences of a hard border,” Spicer said.

Connelly explained how Euroskeptics’ hunger for a “Global Britain” — unchained from the shackles of the EU — came at odds with other citizens’ desire for a strong relationship with Ireland, pulling the country in two different directions. May organized a cabinet symposium to identify a reconciliation point between divided British identities, but a follow-up withdrawal agreement failed to pass.

Boris Johnson, running on a mission to “Get Brexit Done,” succeeded May as leader of the Conservative Party in 2019. Even though Johnson threatened no exit from the EU with or without a deal, according to Connelly, he ultimately met with the Irish prime minister. Johnson agreed to a revised Northern Ireland Protocol, replacing the ‘backstop’ with a ‘frontstop,’ which articulated that Northern Ireland would immediately be a part of the single market and customs union.

“One of the selling points of the Northern Ireland Protocol was ‘best of both worlds.’ Northern Ireland had pretty much frictionless access to the EU single market, with 450 million consumers across 27 countries, but it also had pretty much frictionless, or minor friction, access to the UK market,” Connelly said.

After years of negotiations, Connelly explained how Ireland and Britain agreed upon the Windsor Framework, which adjusted the operation of the Northern Ireland Protocol to avoid hard borders, preserved the Good Friday Agreement and guaranteed access to both the EU and UK markets.

In January 2024, the UK government published its “Safeguarding the Union” deal, a unilateral agreement to restore institutions to operation. After several years of negotiation, Connelly described the Brexit deal as having reached somewhat solid ground.