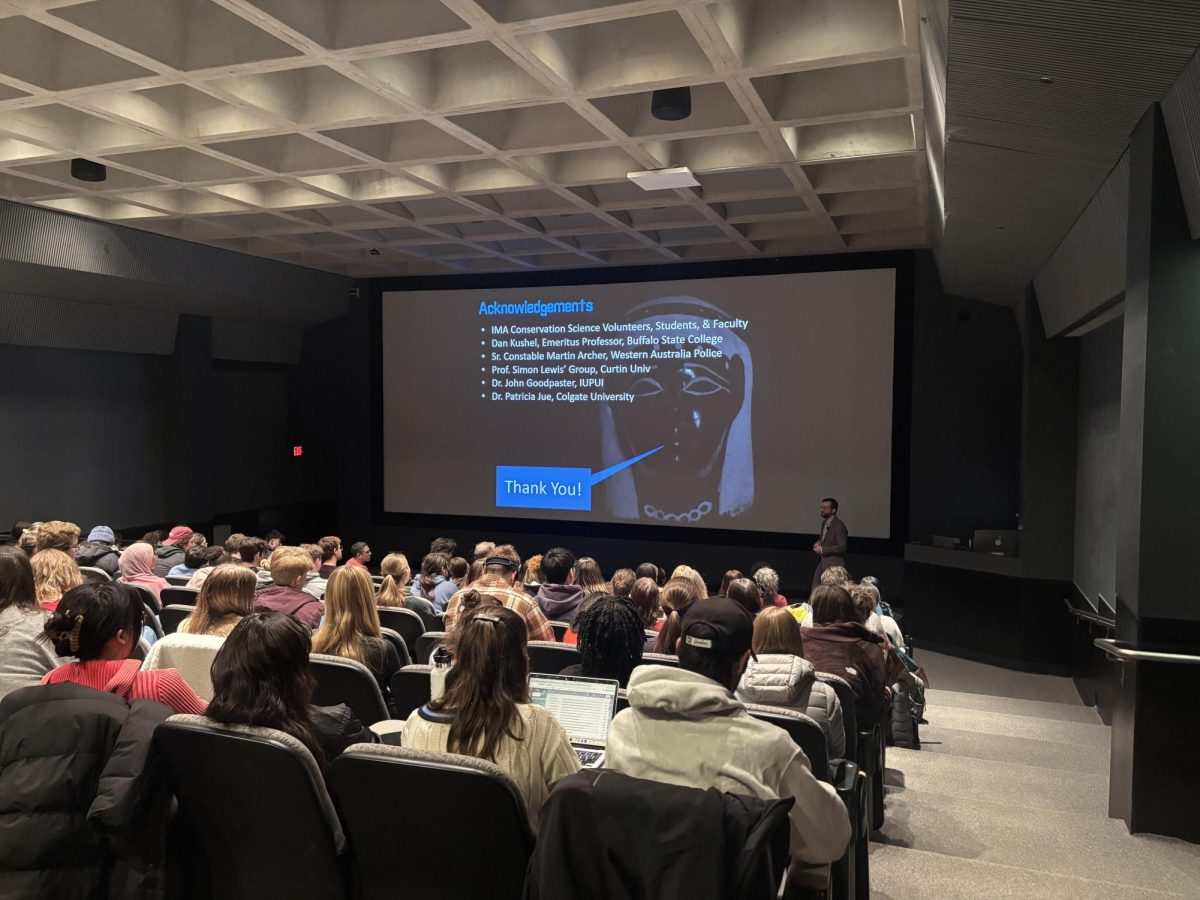

Former Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations (UN) Ramesh Thakur visited Colgate University to discuss his principal work, the responsibility to protect (R2P) doctrine, on Wednesday, April 17. Thakur’s lecture was well-attended by students and faculty, especially from within the political science department. The lecture covered the development of the responsibility to protect principle, examples of its implementation and a discussion of where Thakur believes it falls short.

Sophomore and political science major Boen Beavers invited Thakur to speak through the political science department’s Kulla Lecture Fund, a program that allows students to invite speakers to Colgate who they think will engage the campus.

Associate Professor and Chair of the Political Science Department Valerie Morkevičius spoke about the process of inviting Thakur to campus.

“[Beavers] reached out to me to say he had read Professor Thakur’s work [in class] and he thought it was really interesting,” Morkevičius said. “I said, ‘Well, okay, let’s do it. Why don’t you write him an email and see if he’ll come?’ So [Beavers] wrote to him, and Professor Thakur agreed to come.”

Thakur previously worked as a professor but is now looking to step away from academia and speaking engagements. For Beavers’ invitation, however, Thakur changed his mind.

“I decided to accept, mainly because it gives me an opportunity to reflect back on the origins, successes, setbacks and current status on a topic that is likely to be the defining legacy of my professional life,” Thakur said. “It’s an opportunity to look back at it all and see where we are.”

Thakur began his lecture by discussing the context that led to the responsibility to protect doctrine and how he defines the term.

“In simple terms, I think it’s the organizing principle by which the international community actually fully authenticated structures and procedures of the United Nations and responded to outbreaks of mass atrocities inside sovereign jurisdictions,” Thakur said. “It’s a means of trying to strike a balance between institutionalized indifference, as represented in the Rwandan genocide 30 years ago this month, and unilateral intervention, as happened in Kosovo in 1990.”

Sophomore Desiree Rigaud attended the lecture after having read the responsibility to protect doctrine in a class taught by Morkevičius.

“We had read the R2P doctrine as well during class, in correspondence with a Rwandan Genocide simulation project that we had, so it was just kind of a way to get clarity on the concepts we had spoken about in class and be able to hear [from] the person who actually wrote it — how his views have evolved and how much he actually still stands behind and corroborates the concepts within it,” Rigaud said.

Thakur discussed how working under former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan inspired him to start building the responsibility to protect doctrine. Many countries had called for humanitarian interventions in the UN, but there was no formal process. By writing the responsibility to protect doctrine, Thakur set out a new international norm for when countries inflict harm on their people. Overall, Thakur wanted to show that the impact of people caring about problems can create a change.

“We can’t go around solving all the problems on our own, but there are some things we can do and try to do,” Thakur said. “Most people can’t be bothered — that’s fine, but it does need enough people to care about it if you want the UN to make a difference. Then it ought to be the case that the United Nations helps channel these ideas and good intentions into better outcomes.”

Morkevičius was surprised by how Thakur’s experience in the UN impacted his view of states and power dynamics. She found that it differed from what she expected after originally reading the responsibility to protect doctrine.

“Intellectually, I was a little surprised that he is, in international relations terms, as stateist as he is — I would’ve expected him to be a little bit more critical of the status quo,” Morkevičius said. “I think it’s interesting to think about how working with and within an organization like the United Nations might give you more of an appreciation for ordinance and stability.”

Thakur described responsibility to protect as a last resort option for countries to use when intervention is needed most. In this description, however, Thakur emphasized that countries do not all need to exhaust all options before going to the last resort.

“[The idea is to be] starting with these warnings and using force only as a last resort; however, that last resort is a conceptual last resort,” Thakur said. “It doesn’t mean you have to try every other option. You could conclude that you have to use force to [motivate], then you go through that.”

Thakur’s specification of last resorts was one area where students who read his work were able to gain further clarification. This was the case for Rigaud.

“The whole concept of him saying that he sees it as a last resort and talking about how it’s not a sequential last resort but a conceptual last resort was something very different from my initial reading of it,” Rigaud said. “I saw it being used as something more preemptive and having an aspect to it as prevention, whereas the way he spoke about it was having it be for rebuilding and sort of this post-facto concept.”

The lecture both provided history and acknowledged shortcomings, while addressing the overall legacy of the responsibility to protect doctrine. Morkevičius also invited students from her courses to a dinner and lunch with Thakur, where they had the opportunity to continue discussions on the responsibility to protect doctrine and direct questions at one of its original creators.