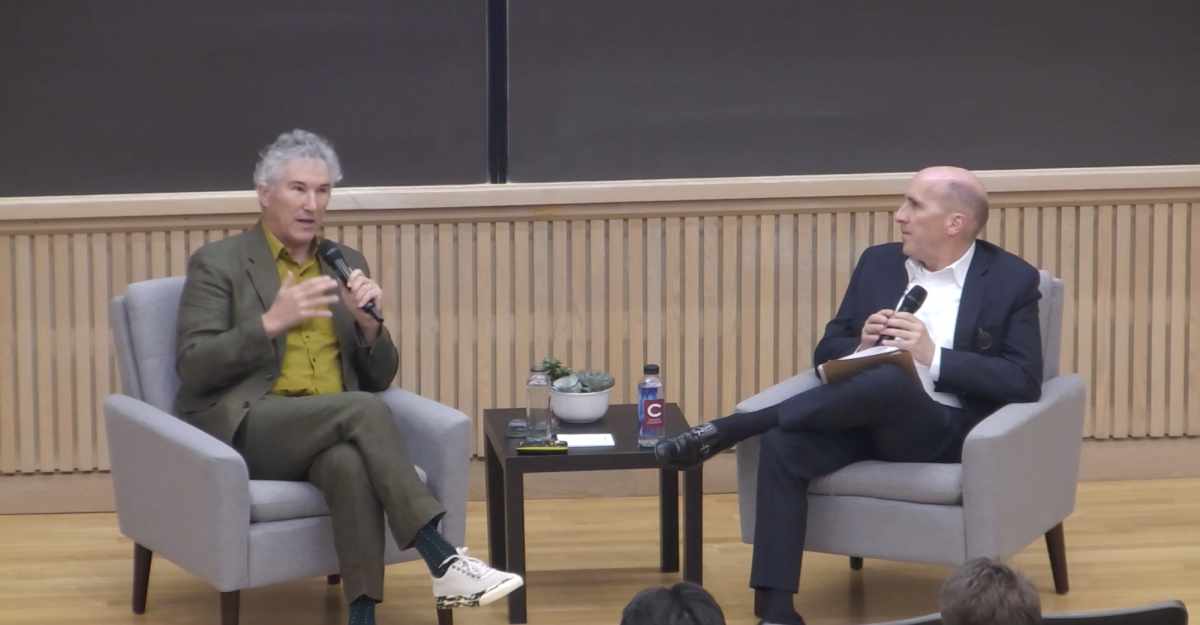

The Colgate University philosophy department hosted Sarah Buss, professor of philosophy at the University of Michigan, to discuss her paper, “Why the Moral Point of View is Not a Fully Coherent Point of View,” on Tuesday, April 16. The Elias J. and Rosa Lee Nemir Audi Lecture Fund sponsored the event, which was moderated by Jacob Klein, associate professor of philosophy at Colgate.

Buss’s paper argued that virtues could not form a unity and that certain moral ideals pulled in opposite directions in circumstances of moral dilemmas. Buss treated the lecture as an occasion to defend her claim supporting the impossibility of a perfectly integrated moral point of view.

Buss presented her defense in two sections. In the first section, Buss explained why virtues cannot form a perfect unity, reading aloud to the audience an excerpt from her paper.

“Insofar as natural beneficence and natural justice are the raw materials from which we develop our capacity to appreciate what we have sufficient reason to do, and to respond accordingly, we cannot develop this capacity without being disposed to see our responses under different substantial descriptions,” Buss said. “In order to develop into a virtuous human being, we must rely on dispositions that are impediments to the unity of virtues.”

In the second section, Buss meticulously dissected the partly contingent reason why the universal “we” cannot have a fully coherent moral point of view. She argues that a non-contingent conceptual strain exists on the unity of virtues. According to Buss, this coherence is unachievable because we subscribe simultaneously to the irreconcilable ideals of mutual respect and human solidarity. As Buss explained, mutual respect says we need to prioritize the interests of our loved ones over strangers, while human solidarity encourages us to find compatibility and unity in humanity as an abstract entity.

Buss used the ideals of respect and solidarity to exemplify her theory. According to Buss, the two virtues express two counterposed conceptions of what it means to be “one among many,” and are thus irreconcilable. Respect, inextricably bound to the virtue of love, means looking out for the interests of those you care for. Buss argued that human solidarity does not fit this mold.

“According to solidarity, to be ‘one among many’ is to be a member of the human community, a fellow traveler, constrained by one’s actions in the fact that we are all in this together, whatever this turns out to be,” Buss said.

Buss also incorporated film and media studies into her discussion on human solidarity. She mentioned the 1995 movie “Quo Vadis, Aida?”, a war film about families displaced when a Serbian army takes over their town. In prioritizing the safety of her loved ones, the protagonist Aida acts in accordance with the idea of partiality to those closest to her. In doing this, she neglects many strangers, despite them being under similarly perilous circumstances; she fails to embody the ideals of human solidarity.

Lyu Zhou, visiting assistant professor of philosophy, found this example particularly striking.

“In this example, on Professor Buss’s construal, solidarity was in tension with partiality to one’s beloved, both moral ideals to strive after,” Zhou said. “It would be interesting to ponder what an advocate for the unity of virtues could say in this case.”

Buss further rejected the idea of supererogation; a supererogatory path is one that is morally good but more than necessary, especially when another less taxing path is acceptable. Buss asserted that the idea does not provide insight into the guilt and shame people feel when they fail to go beyond the minimum requirement or expectation. This lack of nuance, Buss argued, reflects the conceptual impossibility of the idea philosophers had in mind when discussing supererogation.

She argued that there is no determinate idea of morality and that one’s assessment of moral permissibility is equal to one’s assessment of the moral significance of helping, given one’s other ideals. If, for example, a circumstance does not require beneficence, then what a beneficent person would do depends on what a just person would do.

To further support her theory, Buss used the example of a mother reading bedtime stories to her children. She posed that someone who has internalized the ideals of motherhood would not feel obligated to read her children a determinate number of stories each day and would, moreover, not think she was a ‘better’ or ‘worse’ mother than someone who read fewer or more bedtime stories. Buss asserted that the validity of claiming a superior manifestation of motherhood according to the number of bedtime stories read is constrained by the hierarchy of virtues.

“This judgment makes no sense, unless it’s the judgment that in such circumstances the demand associated with the ideal of motherhood trumps the demand of one’s other ideals of teacherhood, wifehood, daughterhood, citizenship and so on,” Buss said. “If we believe that a better, more admirable mother would read an extra bedtime story under these circumstances, then we believe that if one is a mother oneself, and does not read the extra bedtime story, then one can be criticized from the point of view of one’s own ideals of motherhood.”

Buss did not shy away from the limitations and caveats of her argument. She pointed out that if someone were to have a strictly determinate idea of motherhood, the belief would certainly be that a better mother would read the extra book.

Buss further developed her argument by claiming that it can also be applied to the ideals of respect and prudence.

Buss’s theory roused lively debate in the post-lecture Q&A session. Zhou was amongst those who disagreed with Buss, sharing in contrast to Buss’s theory the belief that all virtues are unified under the fundamental virtue of justice and that each fellow virtue is simply an aspect or circumstantial manifestation of justice.

Despite their opposing views, Zhou thought their discourse was very meaningful and found Buss’s theories on the partiality of human solidarity thought-provoking.

“Professor Buss’s talk and our exchange during the question-and-answer session prompted me to critically reflect on whether this alternative proposal was viable, after all,” Zhou said.

Sophomore Perin Romano, a student new to the philosophy department, found Buss’s lecture thought-provoking, especially as it challenged concepts she’s learned thus far.

“As a student who is just beginning their studies in philosophy and ethics, it was so cool to hear a theory about morality that juxtaposed what I had learned in my earlier classes,” Romano said. “Not to mention, I found that Professor Buss was an engaging speaker, and I appreciated how she was able to defend her points when objections were raised. Overall, I loved the talk.”

Philosophy students had the opportunity to join Buss for dinner at the Hamilton Inn following the lecture.

Buss’s talk argued against the coherence of morality and the determinate idea of morality. She defended the claims in her paper in two segments, asserting that virtues pull in opposite directions within circumstances of moral dilemma and, therefore, cannot form a perfect unity.