Beneath the visage of an American political landscape marred by polarity and vitriol lies an even grimmer underbelly named apathy. Apathy — that is, what I label our collective and growing estrangement from all matters political, civic and likewise — is the only threat to American morality ever salient enough to be existential. Because it was never the protests in the streets that threatened the kernel of democracy, nor was it the culture wars or the charged debates. It was the moral paralysis that rendered static our passion to engage in justice, liberty and right. I argue that alienation from politics was never the solution to contention, and political apathy threatens identity.

Political apathy can be defined as a disinterest towards the nature and concerns of politics. It can manifest itself as both a physical and psychological disengagement — that is to say, one not only performs less civic duties (e.g., decreased voter turnout) but also thinks less about them (e.g., information apathy, desensitization from current events). It is important to distinguish political apathy from apoliticism. Whereas the former represents an estrangement from the values and meaning of politics, the latter may maintain these things while simply choosing not to express them. But while an apolitical person may still hold strong beliefs about politics, a politically apathetic one could reject the initial premise of having a political belief.

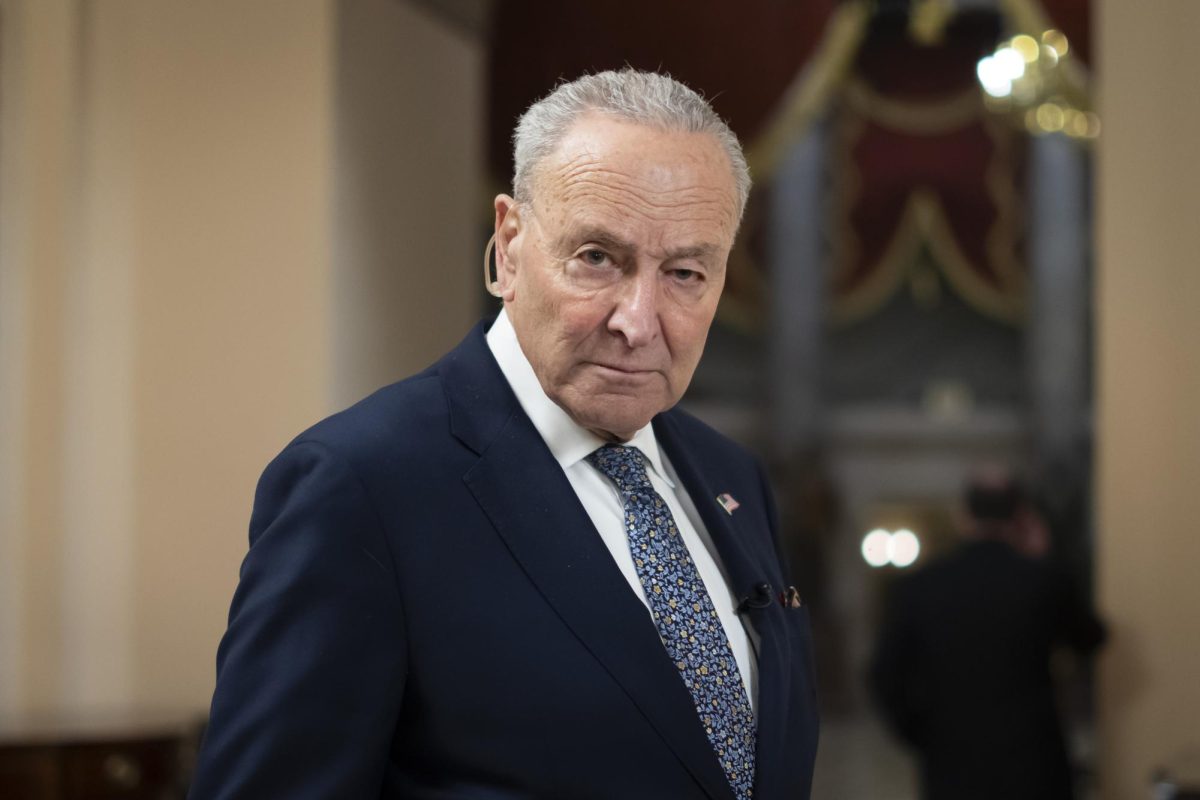

It may be hard to imagine that our increasingly polarized political climate lends itself to such high political apathy. Intuitively, these two conditions seem paradoxical because intense polarization suggests intense enthusiasm, which would run contrary to apathy. Yet polls show otherwise. A survey taken by NPR, Ipsos and the Medill School of Journalism after the 2020 presidential election found that a majority of poll participants felt that “voting has little impact on their lives,” and 53 percent believed that the results of the election would be insignificant. These trends existed across income and educational attainment lines.

A more recent poll by Pew Research Center published in 2023 found that 63 percent of voters lack confidence in the U.S. political system going into the future, and a mere 16 percent holds trust in the federal government at least most of the time. Exhaustion, followed by anger, were the two most popular emotions felt by Americans when politics came to mind.

This is a bleak look into what the future may hold for American politics. A country lacking civic interest is one willing to allow its government to deteriorate. If the fundamental theory behind a democratic republic is that the government is informed by popular sovereignty, what do these statistics say about our belief in democratic principles? If the people are the first and last source of checks and balances against power, what is the implication of a national consciousness which has grown largely apathetic to the tides of power?

These broader questions about the security of democracy have been posed before. I argue a secondary detriment of political apathy can be observed not just on the macroscale, but on an individual basis. I believe politicism is inextricably linked to identity — our imbued construct of self, informed by both nature and environment.

The decline of confidence in civic society represents an apathy not exclusive to political affairs, but also a more general sense of morality. Insofar as the results of an election have practical impacts for the wellbeing of a nation’s people, a disengagement from politics represents a disengagement from a concern towards others. The sanctity of individuals rights and of personal liberties is constantly represented throughout elections. This being the case, an unwillingness to be political is an unwillingness to legitimize such liberties. It could be argued, furthermore, that so long as politics affect foreign affairs — see Ukraine and the Gaza strip for examples — a decline of political concern is a broader decline of worldly concern. Worldly empathy, then, is alienated from one’s personal identity to some degree. This, I believe, is the first casualty created in the trend of political apathy, and it is unlikely to be the last.