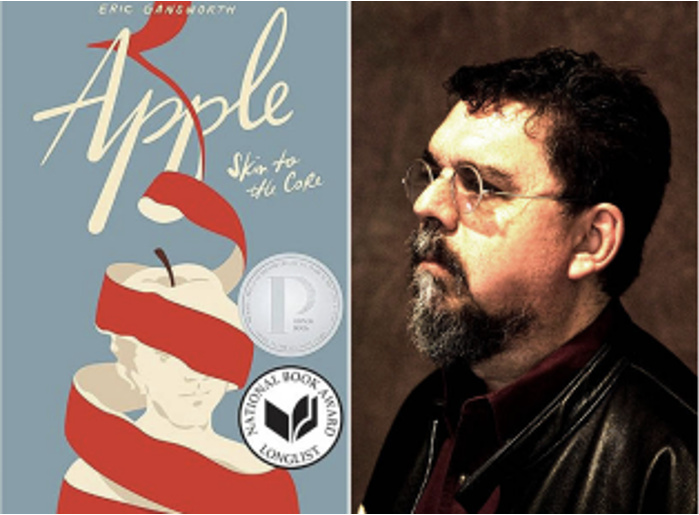

As author Percival Everett prepared to write his acclaimed 2024 novel “James,” he reread Mark Twain’s “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” 15 times — almost to the point of nausea. He told this story while speaking to a packed audience on Thursday, Sept. 19 in Olin Hall as part of Colgate University’s Living Writers program, co-sponsored by the Africana and Latin American Studies Program.

“After the fourth and fifth reading, I was fairly sick. I was comatose,” Everett said.

Yet by the 15th time, he was finally prepared to reinhabit the world that Twain created by completely flipping the narrative and construction to focus squarely on Jim, Huck’s enslaved companion.

While a number of recent reviews of Everett’s latest novel — which has been shortlisted for this year’s prestigious Booker Prize — characterized “James” as a retelling of “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” Everett rejected this idea.

“I was not trying to recreate Twain’s work, but necessarily, since it was from Jim’s point of view, I was writing a different story,” Everett said. “Because of my respect and adoration of Twain, I don’t offer this novel as a corrective to ‘Huck Finn.’ I prefer to think of myself as being in conversation with Twain.”

Despite his admiration for Twain, Everett noted that he’s actually harbored an intense dislike of the classic novel since he first read it as a young Black teenager.

“I think that I had written the novel that Twain was unequipped to write, what his imagination could not allow,” Everett said.

While in Twain’s version the story is told primarily from the point of view of Huck, in Everett’s novel, it is Jim’s voice that propels the story. In contrast to Twain’s depiction of Jim as an illiterate slave, Everett recasts the character as an educated, well-read observer of both internal and external worlds with a penchant for literature and philosophy.

In “James,” Everett aimed to challenge the historical image of the enslaved person as superstitious, lazy and illiterate.

First-year Gianna Amatuzzi, a student in the Living Writers course, reflected on the impact of Everett’s narrative.

“I was really impressed by how Everett gave Jim literary and intellectual agency. I think this was especially highlighted by Jim renaming himself to James,” Amatuzzi said.

Everett’s ability and willingness to intertwine a classic text such as “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” with modern themes has brought “James” widespread critical acclaim and punctuates his other equally important bodies of work.

Professor of English and creative writing Jennifer Brice introduced Everett to the audience.

“His novels explore race, politics, gender, power, purpose, the meaning of family, the tug of war between heart and mind,” Brice said. “[Everett’s] fingers [are] laced firmly against the pulse of American culture.”

The author’s presentation on Thursday to Colgate students marked the first public reading of “James” the novelist has done since the novel was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Yet despite the recent accolades, Everett is ambivalent towards his own work.

“I write these things, and I’m supposed to like them, but generally I don’t. I forget them immediately, and they just become a part of the shelf of those things that I don’t think about,” Everett said.

While Everett’s novels explore pressing social themes, he affirmed that his work serves an internal purpose above all.

“I don’t think about the audience when I write. I write because I want to be part of the conversation,” Everett said.

Everett’s distinctive attitude towards his work perhaps reflects his unique trajectory as an author. He first studied philosophy, then mathematical logic and biochemistry and later fiction.

Brice noted that Everett worked as a jazz guitarist, a horse trainer, a tracker and a cowboy. He is both an accomplished abstract painter and a distinguished professor of English at the University of Southern California.

Everett described how his identity as an author reflects the archetype of the “mama bear.” Whether he is painting, writing or studying dog training for his newest book, Everett’s works are ultimately cast out from the den and are left to eat, survive and fend for themselves.

“The one thing they cannot do is come back,” Everett said.