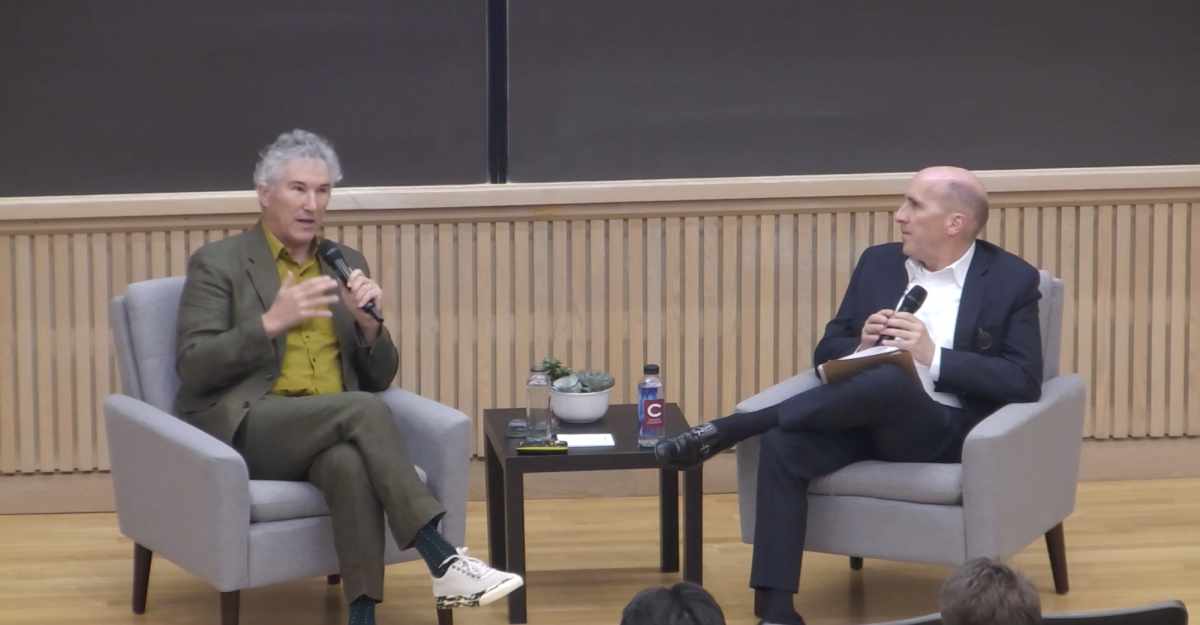

Colgate University’s Lampert Institute for Civic and Foreign Affairs invited back David E. Sanger, White House and national security correspondent for The New York Times, on Oct. 1 to discuss U.S. foreign policy and the upcoming presidential election. With four decades of experience in diplomacy, national security and geopolitics, Sanger wove together hot-button crises and personal stories with high-profile world leaders to a packed room of students and faculty.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist previously visited Colgate in March 2024 to discuss his now-released book, “New Cold Wars: China’s Rise, Russia’s Invasion, and America’s Struggle to Defend the West.”

Sanger drew attention to the imminent war in the Middle East and the feeling of chaos in the world. While politicians in Washington enjoy superpower status, many disagree with the extent of U.S. involvement in international conflicts. Recalling an amusing interview with former President Donald Trump in 2016, Sanger revealed his role in introducing the then-candidate to the term “America First.”

“At the end of the interview, I said to him, ‘You know, this sounds a lot like the old America First movement,’ thinking he would say to me, ‘I know what isolation is. I’m not, you know, Lindbergh from 1939 or 1940.’ Well, of course, it hadn’t dawned on me that he had never heard of Lindbergh’s America First movement. So he looked at me and said, ‘You know, I kind of like the sound of that.’”

Trump’s fascination with America First did not end there.

“Sunday comes and goes. Trump is down in Dallas giving a campaign speech. I get up in the morning and I’m seeing little clips of it on the morning news. He’s standing at a podium, as you can imagine, yelling ‘America First! America First!’ My wife comes down and she looks at the screen, and with that withering look that only a spouse can offer, says, ‘I hope you are really proud of yourself,’” Sanger said.

Not only did Trump embrace America First, but so too did the Republican Party. The concept emphasizes focusing on domestic policy and disregarding global affairs. Sanger wrestled with the implications.

“Can America be ‘first’ if it is not engaged around the world? Are you truly a superpower if you don’t have a presence — political, military and certainly a business presence — in Asia, in Europe, in the Middle East, in Africa, in Latin America? Can you shape the world and make it a place that you want to live in and you want your kids to live in if you are not willing to use both the good and bad of your influence, your hard power and your soft power?” Sanger asked.

Sanger pointed to the most significant developments in geopolitics in recent years, such as the rise of China, Russia and Iran. China’s leader, Xi Jinping, strives to make the country the biggest military, economic and technological power. The nature of international relations sees global powers rise and fall. Sanger wondered if America would spend the money to remain a global hegemon.

“Almost everything about how we think about the next few decades, how we defend ourselves, how we nurture international alliances, how we spend money at a time when our national debt has soared over $30 trillion, is up for contentious debate at home and around the world,” Sanger said.

Did the revival of superpower conflict come out of thin air? What changed in the last 30 years? When America emerged victorious from the Cold War, U.S. leaders predicted a new era of democracy, peace and cooperation. Not only would superpowers come together to solve climate change and fight terrorism, but they would integrate into the West. Sanger witnessed this unbridled optimism and sense of certainty first-hand working in the Washington Bureau of The New York Times.

“When I got there in October 1994, there was an assumption, basically unquestioned around Washington, that the United States, China and Russia, and other nations in their wake, would fundamentally come together and work under Western design rules,” Sanger said. “[President George W.] Bush was dangling in front of Putin the thought that Russia might join the European Union and become part of one market. More importantly, there was discussion of how Russia might join NATO, the military alliance created to contain the old Soviet Union.”

Sanger characterized our expectations as living in a fantasy. The reality of these competitors’ intentions manifested far differently.

“The nature of that fantasy was that we managed to overemphasize every sign of cooperation and underemphasize every indication that these countries were going off and pursuing their own interests in their own ways, and maybe reverting back to old behavior,” Sanger said.

As politicians consider becoming a full competitor with China, they walk a fine line between capitalism, democracy and national security. Businesses think about economic incentives, and presidential candidates think about keeping the electorate happy, both of which can risk national security.

Senior Danielle Silverman attended the lecture and found these conflicting interests fascinating.

“Something I found really interesting was Sanger’s discussion of TSMC, the Taiwanese company that makes the computer chips that are causing heightened tensions between China, Taiwan and America. I think it’s really interesting to consider how consumerism, production and material goods can sit almost on the front lines of international conflict. It’s most definitely something to think about in the future, especially as the human race becomes more reliant on technology,” Silverman said.

Sanger’s lecture gave students a historical framework for navigating the geopolitical dynamics rocking the international stage.

Chad Sparber, professor of economics and director of the Lampert Institute, anticipated that students might walk away with a deeper interest in some of the topics Sanger discussed.

“I hope students learned more about the importance of foreign policy. It would be great if someone in the audience was inspired to learn Chinese or Russian — important skills for improving global security and our national interests,” Sparber said.