From the mountain of election day reports, maps, tallies, polls and figures, only one piece of journalism stuck with me: a series of threads on X by journalist Michael Tracey, which captured average voters in Pennsylvania. In each post, Tracey included a photo, the voter’s name, the candidate they voted for and the reasons why they voted for their candidate.

At first glance, the posts are nothing special. The photos are simple and even unflattering; everyone looks fairly normal, and their rationale is nothing extraordinary. Yet, in the snapshot of each life, there’s a charmingly human element that was notably missing from most coverage of this election.

In the days preceding the election, I heard a lot about polls, podcasts and abstract trends, but very little about how the actual voters were feeling. It was almost like pure statistics — analyst Nate Silver’s absurd “80,000 simulations” tweet and Ann Selzer’s way-wrong Iowa poll come to mind — were supposed to replace the voices of real Americans.

Similarly, I didn’t hear a lot about actual voters post-election either. I heard about a rightward shift and various strategic failings, but little else. There were no rallies or protests to speak of, little of the 2016-esque outrage wave on social media. There was an uncharacteristic radio silence.

But the human reaction did remain, only with a different tone. Instead of taking to the streets, dissatisfied voters resigned themselves to disappointment and isolation. Echoes of 2016 were still audible in a number of circulating posts that encouraged disowning family and friends who had cast the “wrong” vote.

But in light of Tracey’s snapshot profiles, there was something I couldn’t square about such an attitude. Among the politically diverse sample of Pennsylvania voters, not a single one seemed particularly radical or worthy of an off-hand cold-shouldering. They seemed like people trying to make their voices heard, whether I agreed with their assessment or not. The reasoning for some observers — liking Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Tulsi Gabbard or Trump’s knack for consistently producing funny moments, for example — might not, in my opinion, be a good reason to choose a presidential candidate, but I think it offers more than an opportunity for judgment. It tells us how real people really feel about their country.

Most people are not political savants, and their opinions are fairly immanent. When grocery and gas prices go up, when they can’t find a job, when a relative dies from opioid addiction, when they’re worried about going to war, they vote for the person who they think will solve those problems — hardly an unthinkable position. Even if you think they’re gullible, ignorant or evil, it’s hard to deny that each voter has at least something to say. And that something, I think, cannot be reduced to demographic trends or moralization. People are complex, unlike tailored and prepped politicians. Not everyone has a one-liner or a grand statement to make about the state of the union. But that doesn’t make them any less worth listening to.

While I think you can choose who you associate with, your right comes with a qualification: You have to know who a person is and what they think before you make such a decision. And no one fits neatly into a binary political category, as our electoral system might suggest.

I don’t see a vote, in most instances, as an absolute endorsement of everything a single candidate has ever said or done but an exercise in power — a request to be heard by the rest of the country. And when people are asking to be heard, you can’t just ignore them. As far as listening goes, a broad-strokes block button is fairly useless.

For this reason, the idea that every single voter with whom one disagrees is aiding and abetting the collapse of the country is simply detached. Regardless of how you feel about their candidate, the voter is not their candidate. They aren’t an accomplice; they are a person with feelings about the country that should be respected. As ignorant as one might think an alternate opinion is, the ultimate ignorance is believing that it has nothing to teach you.

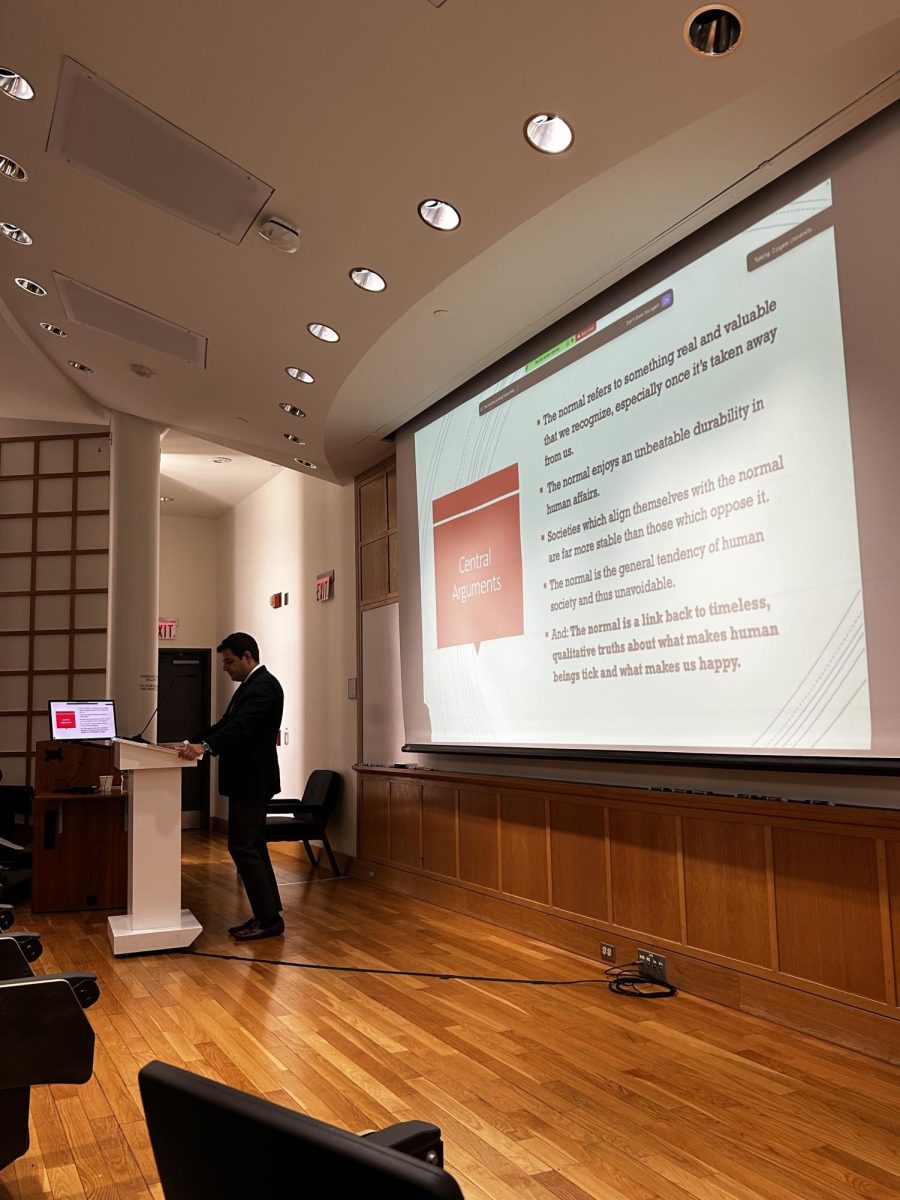

Even if the human motivation for engaging with alternate viewpoints isn’t convincing, maybe a pragmatic one is more moving. If you’d like the country to think like you do, you have to meet it halfway. Refusing to engage can be costly. In this election, one of the perceived missteps of the Harris campaign was an over-emphasis on celebrity endorsements and not enough attention to the concerns of the average voter — a classic example of an insurmountable gap between what you wish voters cared about and what they really care about.

In the future, this campaign strategy won’t win elections. Through social media, people are increasingly exposed to the opinions of other Americans and are less easily fooled by these forced celebrity narratives. The adjustment, then, has to include the voices that are trying to be heard. Leaning into the people you most disagree with, rather than shunning them, is the only way to turn the tide of your community and the country in your favor.

No matter how cynical your motivation is, engagement with people who disagree with you will be invaluable in the coming years. The opinions of Americans are shifting and 73% of voters were dissatisfied or angry about the country’s trajectory, but things are still malleable. To withhold empathy from a given half of the nation is bad politics and a fatal concession.