The morning after the election, I walked into my 11:20 class to tired, uneasy faces, the air thick with quiet chatter. Regardless of how they felt about the election results, many students seemed to be hoping — or perhaps even expecting — that our professor would open up the floor for discussion. When our professor spoke, she offered us just that: “I want to give you all a space to talk about the election, if you want.” But instead of an immediate rush of conversation, there was only silence — five long minutes of it.

In those five minutes, I couldn’t help but wonder why no one, including myself, was jumping at the opportunity to discuss the election. Perhaps it was because we were all unsure of how to start — or if we even wanted to start. Perhaps it was the fear of being judged or labeled.

In today’s world, political opinions have become polarized, reduced to simple labels more than ever before. With the rise of social media and 24-hour news cycles, many people — particularly young people — have become entrenched in political extremes. While these developments have made politics more accessible, they also make it extremely challenging for one to express nuanced or moderate views. In some circles, the language used around political issues has become so charged that it’s hard to have a conversation without feeling like you’re at risk of being labeled something you’re not. With political parties carrying specific and single-faceted labels, sharing a personal opinion that aligns with a particular political party can quickly lead to being labeled as a socialist, racist, a homophobe or worse. These labels can carry a lot of weight, and for many people, the fear of being wrongly categorized is enough to silence them.

This kind of environment makes it hard to have productive, open discussions. When everyone is on edge, when the fear of being labeled or judged is so pervasive, it becomes difficult to engage with people who may hold different views. It’s easier to retreat into silence than to risk having your entire character or identity reduced to a single label. This also applies in academic settings where students are expected to form and defend their ideas yet often feel like they must tread carefully to avoid offending anyone or being labeled as problematic. I think this tendency to reduce people to their political opinions is one of the reasons why so many students, and people in general, are hesitant to speak up. This kind of binary thinking — where you are either with us or against us — clearly limits our ability to engage in meaningful dialogue and foster collective progress.

As the silence in that classroom stretched on, I realized that what we were missing wasn’t just an opportunity for discussion. We were lacking the trust we should have in one another to engage with differing opinions, including those of our professor. This isn’t to say that the fault lies with our student body. Again, it’s a reflection of the broader social climate that makes such conversations so challenging — even in a class literally titled “Conversations,” a part of Colgate University’s Liberal Arts Core Curriculum.

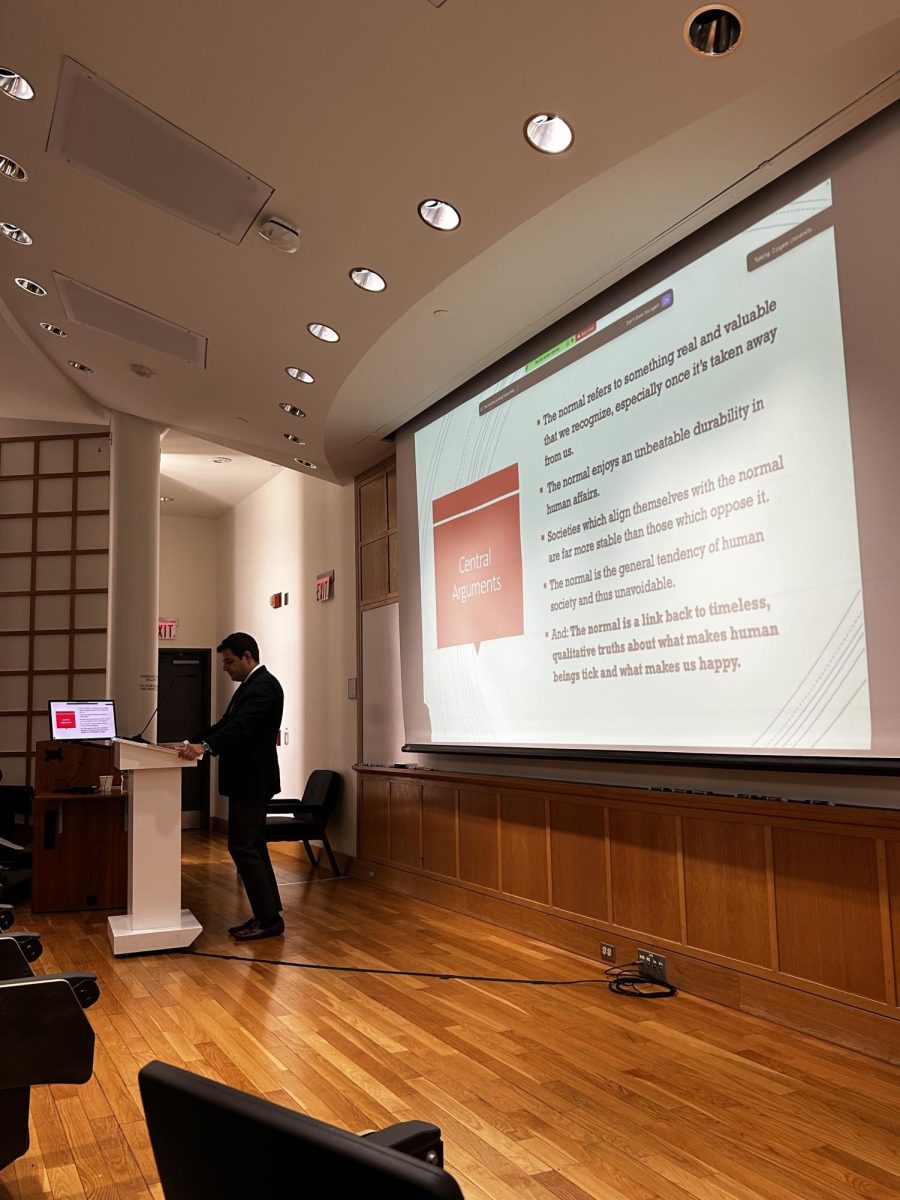

The following class period, our professor started by talking about why she wanted to give the class another opportunity to discuss the election. She emphasized the importance of trust in our classroom and said that her ultimate goal as an educator was to allow students to talk to one another without fear of judgment. She noted that no one can assume what the prevailing political opinion in the room is, or even her own. Only then did hands begin shooting up.

This moment was exactly what I believe is needed in our academic curricula as a potential solution to the silence that stifles our ability to productively engage with one another. It’s not about “getting centered” or watering down opinions to make them palatable for everyone — it’s about fostering informed conversations where individual opinions survive.

I must admit that when political discussions are initiated by the instructor, they can often feel weighted by the instructor’s bias, which can create reluctance to participate. I’ve been fortunate to have a professor who facilitated a thoughtful and inclusive conversation, but this shouldn’t be left to individual instructors — it should be institutionalized. We need to create environments in academic settings where open dialogue is not just encouraged but actively protected. When discussing political theories or foundational ideas — a central part of the Core Curriculum — we shouldn’t be afraid to draw contemporary connections, rather than leaving these discussions confined to the past. In order to move past the silence that stifles meaningful engagement, we must create educational spaces where trust, open mindedness and respect for diverse opinions are foundational to the learning experience.