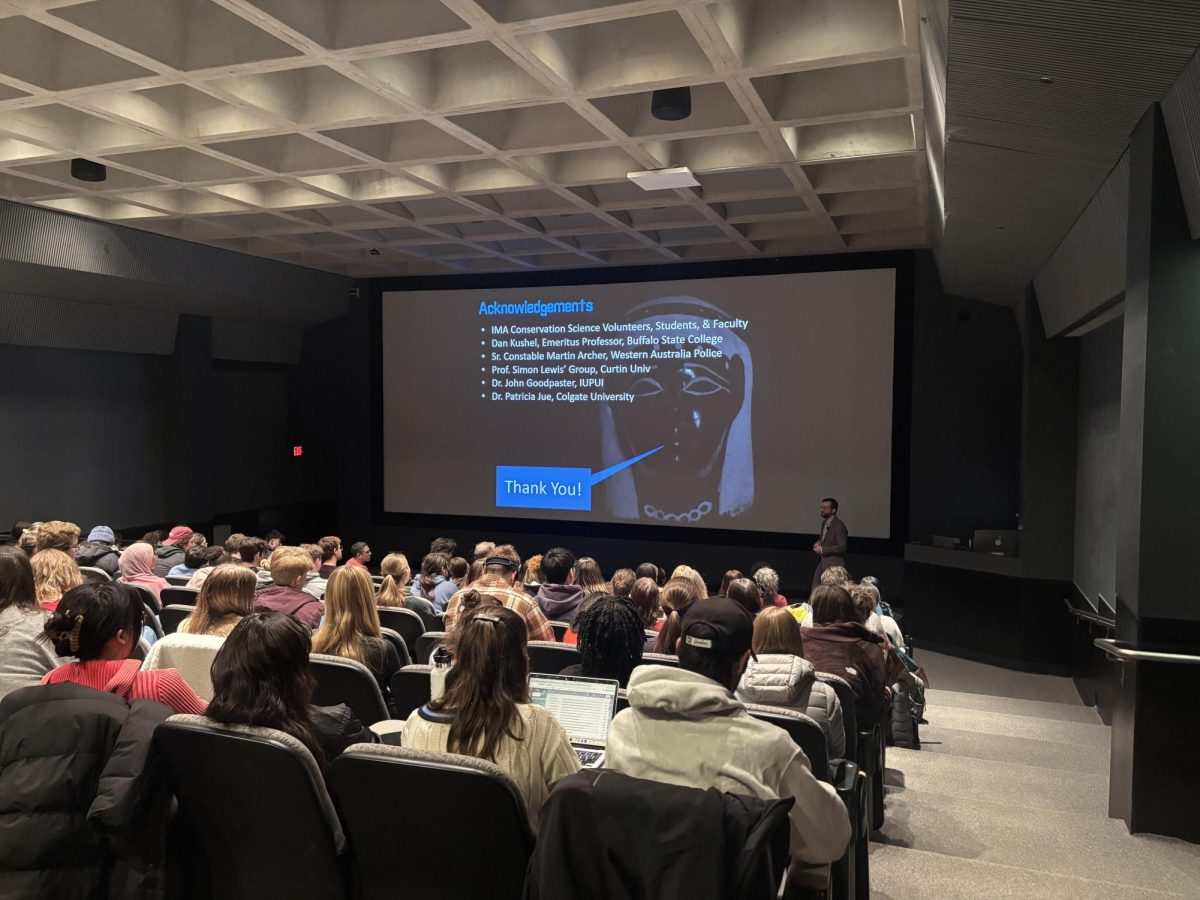

On Thursday, Feb. 6, the Colgate University classics department hosted Dr. W. Brent Seales to discuss the virtual unwrapping of the iconic Herculaneum Scrolls via innovative machine learning. Seales, the Stanley and Karen Pigman chair of heritage science and professor of computer science at the University of Kentucky, chronicled his years-long journey to uncovering the 2,000-year-old classical texts that escaped the fury of Vesuvius.

The Herculaneum Scrolls, buried and carbonized by the Mount Vesuvius eruption in 79 CE and then excavated in the 18th century, are from the shelves of The Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum, Italy — the only library to have survived from antiquity. According to Seales, these scrolls presented an enigmatic challenge: preserved by the pyroclastic flow of the volcano, yet still lost. His ensuing lecture, aptly titled “On Perseverance” tells the story of the great scientific innovation that rendered these relics unlost.

Seales began with discussions on the origin story of his work as a computer scientist as it intersects the medieval and modern world. The process began in 1995 when he was writing software to restore manuscripts of classic texts. Seales described this work as a window into the novel industry of virtual unwrapping.

He shared a timeline of the unwrapping attempts, which illustrated the immense progress achieved since their excavation 200 years ago. Abbot Antonio Piaggio’s machine — which attached the scrolls to silken thread and attempted to gently unravel them, was used to unroll scrolls as early as 1756 in the Vatican Library with varying degrees of success. Over time, the papyri were doused in chemicals, blasted with gas, sliced, diced and pulverized in various attempts to read them. By 1999, however, more than 400 scrolls remained unopened and methods for physical unwrapping had reached a stalemate.

One of the many scientists on this seemingly impossible mission, Seales envisioned a brain imaging technology to see inside the papyrus scrolls without touching them. Aided by student researchers, Seales began his own unwrapping initiative at the University of Kentucky.

Their tomography — an archaeological technique that uses penetrating waves to create images of sections or slices of an object — software found evidence of carbon ink in the scrolls. The technology didn’t have the right spatial resolution, forcing the scientists to workshop the resolution in a high-energy physics facility. Although the carbon ink was a technical breakthrough for the team, Seales shared his struggles with perfectionism.

“You can’t look at a half-finished piece of magic and know whether it’s good or not. […] How do you get to ‘yes’ when working on something as iconic as Herculaneum? When you achieve it, it looks like a miracle, and when you don’t it looks stupid,” Seales said.

After much trial and error, the team sought the wisdom of the greater scientific community. In March 2022, Seales and Silicon Valley investors led a global competition to read the charred scrolls after he demonstrated that the AI program can successfully extract letters and symbols from X-ray images of the unrolled papyri. Luke Farritor (first place) and Yousseff Nader (second place) separately developed machine learning methods to reveal the ink — resulting in the same findings.

“The software was the key. We’d build a treasure map with open fragments that had visible ink. The treasure map was that we could photograph that and relate it to when we couldn’t see anything. We aligned that: here’s where the ink is, here’s where there’s no ink and here’s the answer,” Seales said.

At long last, the virtual unwrapping project had reached fruition. According to Seales, virtual unwrapping is a non-invasive restoration pathway for damaged written material, which allows the scrolls to be read without physically opening them. This readable version requires a four-step virtual unwrapping pipeline. During step one — segmentation — the software moves through the scroll image by image to produce a 3D model. Step two — texturing — is when the software extracts ink from the data, passing through the scroll a second time and identifying bright pixels that indicate dense material. Next, the software converts the textured 3D surface into a flat plane in a process called flattening. The final step, merging, consolidates the separate images into a final text of five complete wraps.

On Oct. 12, 2023, Seales’ machine identified its first word: Greek characters revealed as meaning “purple dye” or “clothes of purple.” Seales described it as a moment of delirious joy. Colgate Associate Professor of the Classics and Classics Chair Geoff Benson shared in Seales’ rapture.

“A jolt of lightning went through my body when I heard they had discovered the first word on the Vesuvius scroll: purple,” Benson said.

Since the “purple” discovery, the software has identified 16 partial 1.2 meter columns precise enough for a papyrologist to read and translate. Along his path to triumph, Seales faced swathes of setbacks, failed attempts and persistent doubt and ridicule from the public. For Seales, however, the feeling of contributing to the recovery of this ancient history overshadows any external negativity. He attributed the success to his team.

“I named this talk ‘On Perseverance’ because we never would’ve gotten to this point if we stopped trying to find excellence, if we gave up on this miracle,” Seals said.

Sophomore Isabel Costa shared her enthusiasm about this innovation.

“I would consider the Herculaneum scrolls and the technology used to read them to be among the most exciting developments in the classics and archaeological field, so it was fascinating to hear from someone directly involved in the project,” Costa said. “It was fascinating to see how cutting-edge computer programs can bring completely new pieces of literature to light.”

As of now, only 5% of the 12-meter scroll has been discovered, and there are more than 400 scrolls waiting to be virtually unwrapped. Seales’s goal under the Vesuvius Challenge is to open 100 scrolls by the end of 2025.

“My dream would be to read everything that we have and then go back and fully excavate the villa to find if there truly is another wing of the library,” said Seales.

Seales concluded with an impassioned statement on what this project represents.

“Beyond archaeology, beyond AI, we have actual intelligence from 2000 years ago. For me, there’s this immense joy at knowing we’re going to read this literature and we’re going to find out what it says. It’s a new beginning.”