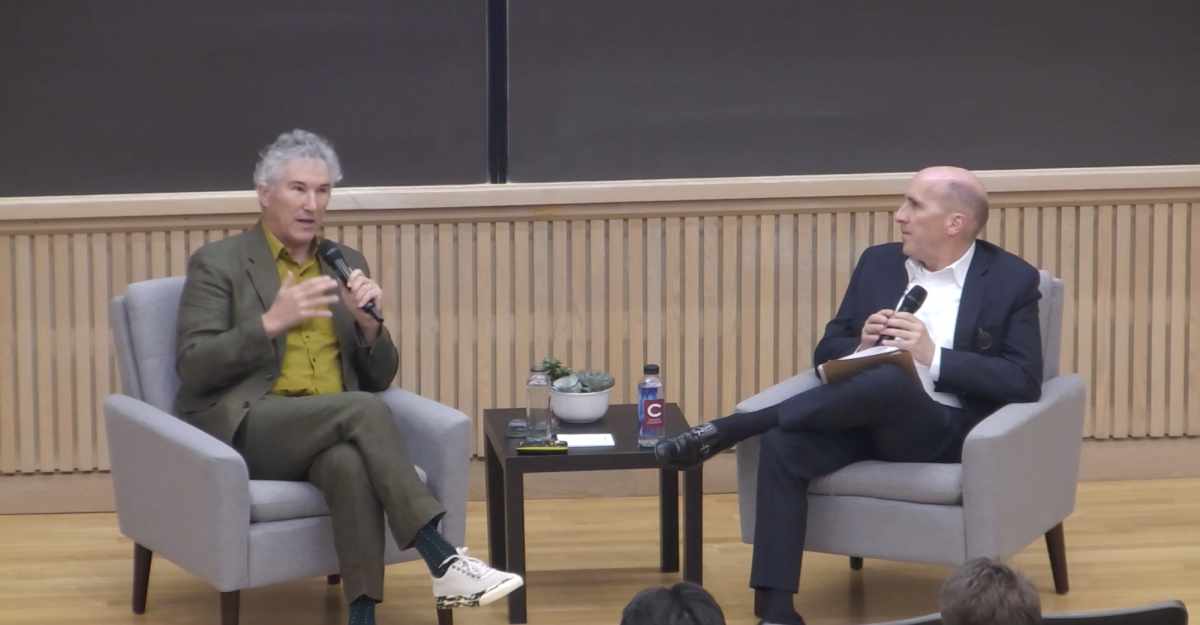

Colgate University hosted Dr. Gregory Smith to explore the intersection of chemistry and art. The lecture, held on Wednesday, March 26, was titled “Solving Art Mysteries Through Chemistry” and delved into how chemists unravel puzzles in the world of abstraction.

Patricia Jue, senior laboratory instructor in the chemistry department, organized the event. Jue and Smith gave presentations at a national conference last summer, and Jue connected with Smith’s talk on a textile turned into a teaching tool. This motivated Jue to invite Smith to Colgate, where she drew attention to their joint pursuit of merging the science and art fields.

“[Smith] and I belong to a small — but growing — group of chemists who examine works of art, and think about how to use artwork and archeological artifacts as a way to introduce chemistry to a broader audience,” Jue said.

Smith holds a Ph.D. in physical/analytical chemistry and completed postdoctoral research at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York, and University College London. A spectroscopist, chemist and analyst, Smith wears many hats, and uses a toolbox of scientific techniques to solve mysteries in the art collection. As a result of his work, Smith received a large grant in 2010 to bring science to the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

“I appreciate the opportunity to tell you a little bit about my field of cultural heritage chemistry, which pans this interface between the arts and the sciences,” Smith said. “It also touches on important ally fields, like forensic science.”

First-year Sophie Goldsbury resonated with Smith’s interdisciplinary methods.

“I think he wanted to be a CSI investigator in another life,” Goldsbury said. “He showed the behind the scenes of a conservation scientist; they have to know a lot from a diverse range of fields.”

The National Endowment for the Arts granted $60,000 to Indianapolis Museum of Art to mount CSI: Conservation Science Indianapolis. Smith spearheaded three exhibitions on how science enhances our understanding of art: “Painting in the Round,” “What Lies Beneath” and “Chemistry of Color.”

“My museum really embraced the forensic nature of the work, which is the clues and mystery and discovery and investigation, to the point that they allowed me to curate exhibitions in the museum that focus on science and technology,” Smith said.

“CSI: Painting in the Round” focused on the benefits of examining both the front and the back of a painting. The people behind the scenes treat artwork like a crime scene — open to investigation and analysis.

“We know that the back of an artwork with its paper labels and inscriptions and wax seals can be just as interesting than the front of the painting,” Smith said.

Smith presented four case studies that highlight the different roles he plays in the museum, and the audience watched Smith determine the mystery date of a textile and unmask a forgery. Jue explained her fascination with the third case Smith presented, on disappearing ink.

“A big concern for art curators is the fading of pigments and dyes. Scientists have played a big role in understanding why this happens and if it can be slowed down. Some artists use materials even though they know they degrade, but this is the first time I had thought about food dyes in this way,” Jue said.

The final case covered ancient synthetic pigments — Egyptian blue first synthesized in 3200 BCE. His team of scientists use Egyptian blue to confirm authenticity or catch art criminals.

Goldsbury explained the ins and outs of this fourth case.

“[Smith] said he was working with some others on testing if Egyptian Blue could be used in the police field as a fingerprint detector. What was really interesting was when he showed how they retouch paintings; apparently, even though you can get the same color, chemically they can be different,” Goldsbury said. “When conservation scientists use a specific analysis, they can tell where a previous artist has covered something or tried to fix something on an artwork. The artist will specifically use different chemicals so that others know which part of a piece was from thousands of years ago, and which was from them. It’s also how they can tell if something is a fake, when it was made, or how to fix a problem.”

Jue hopes students walked away from the talk with a more expansive understanding of scientists’ role.

“There are many ways that chemists can contribute to ways of knowing,” Jue said. “We really are able to give engaging talks, and we don’t always wear lab coats or work in drab looking laboratories, but we have lots of cool ‘toys’ to examine stuff!”