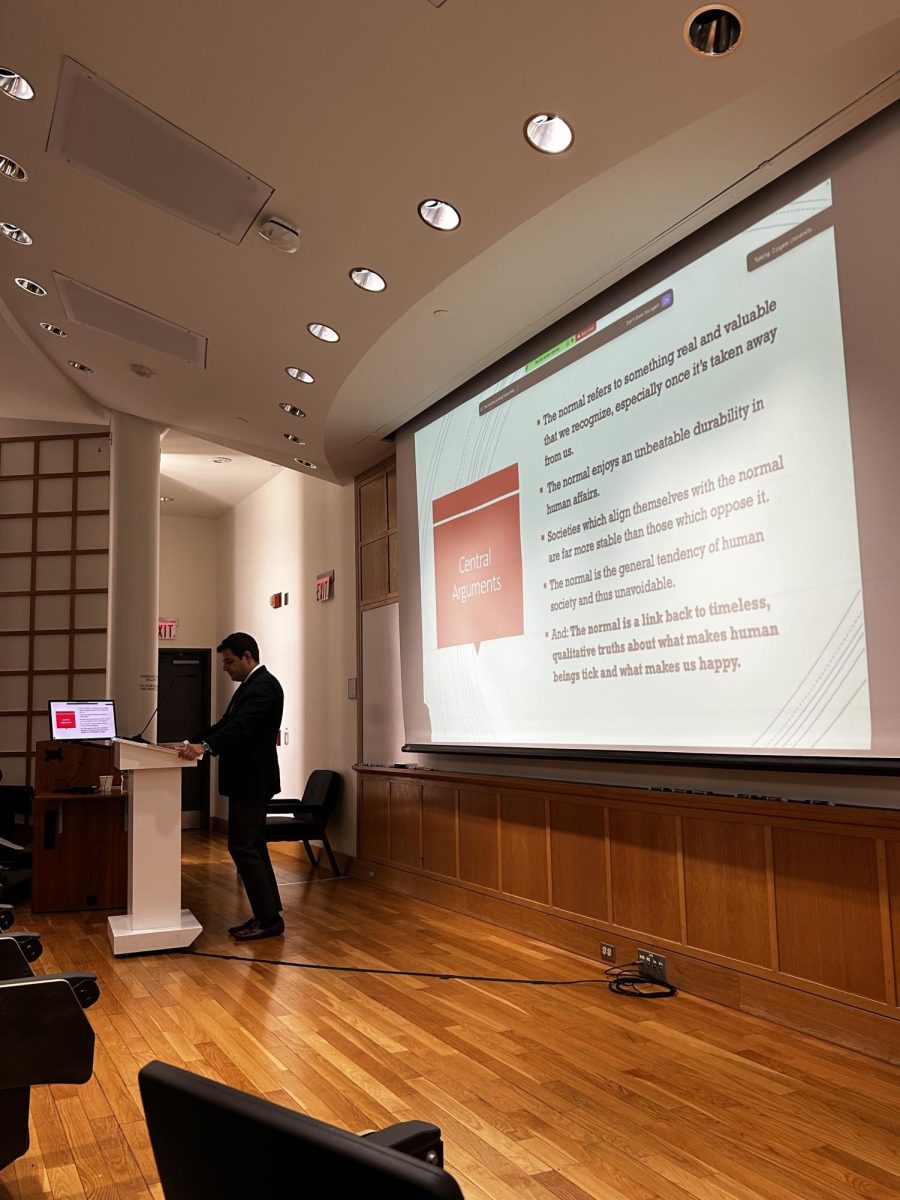

Colgate University Professor of Political Science Frances Wang discussed her new book on Chinese propaganda campaigns, “The Art of State Persuasion: China’s Strategic Use of Media in Interstate Disputes,” on April 2 in Persson Auditorium. The book represents 10 years of Wang’s concerted research and diligent efforts to accurately depict the strategies of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to manipulate public opinion and reflect state values.

After her talk, Wang engaged in a dialogue on the book with Princeton University’s Associate Professor of Politics and International Affairs Professor Rory Truex. She then fielded questions from Colgate students, faculty and others in attendance. Wang’s research is a new look into how one of the most advanced practitioners of state propaganda in human history uses campaigns to incite public outcry over an issue and sedate political dissenters.

Wang’s central thesis states that the Chinese government’s execution relies heavily on media campaigns. Differing from censorship, which focuses on the suppression of information on an event, media campaigns are government-orchestrated, concerted efforts to attract public attention to a dispute.

These media campaigns, she said, include similar features: a deliberate increase in media coverage over a short period of time.

“So it can’t be the media’s natural, reflective reactions to provocative events and has to have the government as the mastermind behind it,” Wang said.

What prompts the Chinese government to launch these media campaigns is a puzzle that asks two central questions: When and why do media campaigns occur, and how do these media campaigns look and work? Wang stated that these questions are important in terms of understanding propaganda in authoritarian states, national security and foreign relations. These questions, which are addressed further in Wang’s book, establish a more complex and accurate image of what propaganda looks like and break out of the simplistic definition that is currently prominent.

Wang addressed this first question through the “misalignment theory”: that the CCP and authoritarian states will use media campaigns to alter public opinion when the public opinion is counter to the existing regime’s policies and intentions. Therefore, in cases where the government and the people both agree on either a hardline or moderate policy, the regime has no need to launch a campaign. However, when there is a significant misalignment between governmental and public opinion, the CCP will conduct media campaigns to redirect the public.

There are two different kinds of this disagreement, each requiring its own kind of media campaign: aggressive and pacifying. In the former, the government is in favor of a hardline policy, while the masses prefer a moderate policy; thus, the government will produce media that incites outrage and stronger emotions to garner support for hardline policies. Pacification occurs when the opposite is true and the government prefers a moderate policy while the people prefer a hardline policy, leading to the production of more moderately toned media.

In addition to the misalignment theory, Wang outlined some of the methods that the CCP uses to manipulate the population in a two-phase process, each incorporating distinct tactics: first, garnering public sympathy, and second, persuading the public.

“The first group of these tactics is focused on connecting with the audience and building their trust, which is necessary for effective persuasion later on,” Wang said.

Authoritarian states do this through legitimating and sympathizing with the sentiments of the public. Another way that authoritarian states manipulate the public is by keeping up the appearance of hardline stances to avoid appearing weak, which Wang calls “hardline posturing.”

“This is important for authoritarian states facing a nationalist public because nationalists tend to equate a moderate foreign policy with weakness or failure,” Wang said. “So, we utilize the appearance of a harsh stance to fend off nationalist criticisms, to preserve the state’s dignity and maintain social stability.”

Authoritarian states also focus on changing opinions. The first way that an authoritarian state does this is by neutralizing the sentiments that had been used to garner public sympathy.

“They allow the people to get on platforms such as social media, so by the end of the day they can let off their steam and remain calm and rational, and also be more agreeable to a moderate foreign policy,” Wang said.

Wang’s research further demonstrated her hypotheses through several case studies where there was a sharp rise in media coverage of foreign affairs within China that coincided with CCP policy and counteracted public opinion.

Attendees of the lecture praised both Wang’s effort and research as well as the finished product presented in her book.

“It’s really an honor to get to discuss this book,” Truex said. “This is a really special book. I really learned a lot from it and it’s a book that I think does a lot of things in political science, but also in public policy for our understanding of China. In the China field, there’s a strange bifurcation where we have people who study China’s foreign relations and international relations, and then we have people who study domestic politics in China. […] This is really exemplary work in that it bridges that divide.”

Valerie Morkevičius, associate professor of political science and political science department chair, attended the book launch and shared her opinion.

“The research is really fascinating, both on the nature of public opinion and how the government can use it,” Morkevičius said. “Her research has significant real-world implications and can be utilized for future policy.”