CONTENT WARNING: This story contains brief mentions of suicide.

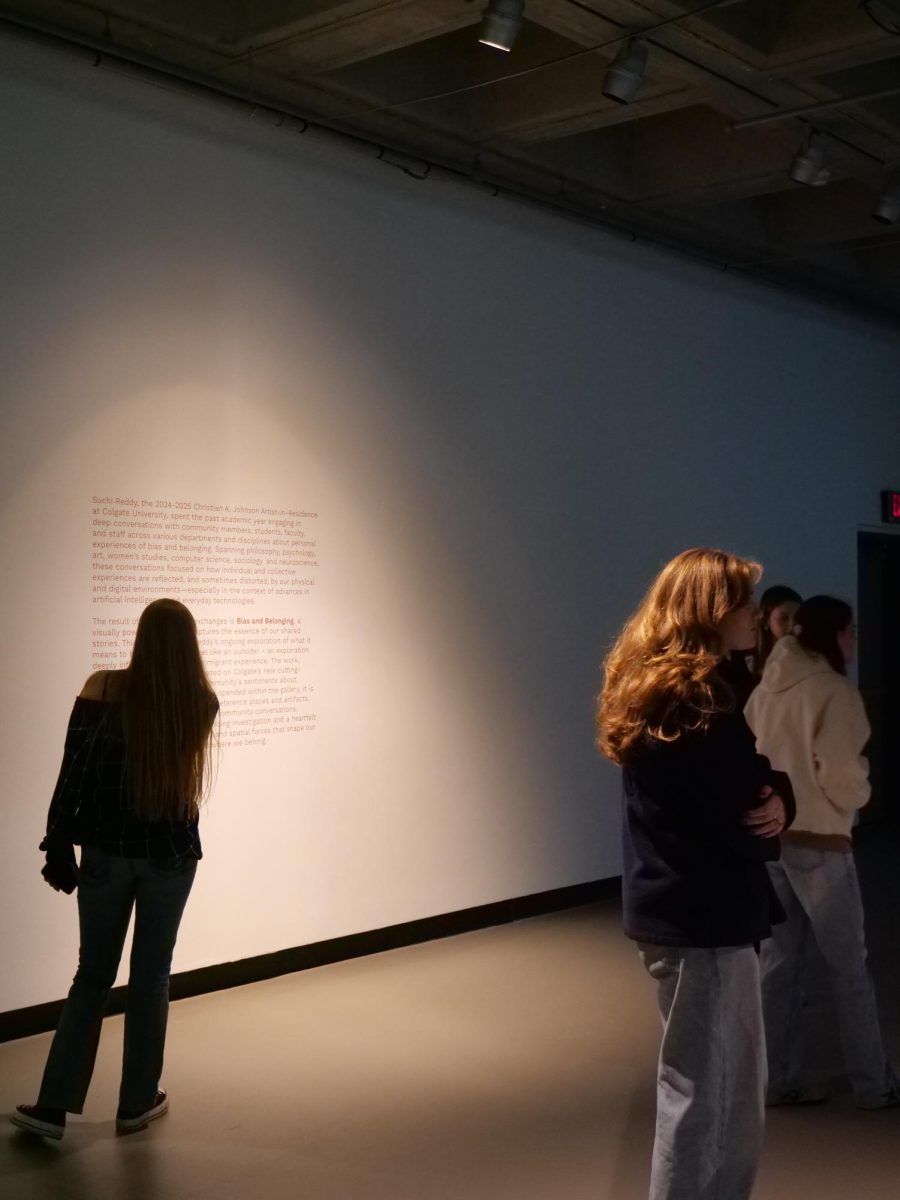

I’ve spent the last four years traversing the rolling upper campus of Colgate University — through rain, snow, the tail end of a global pandemic — unintentionally shielding myself from the histories of protest that permitted my expedition in the first place. Somehow, it took until only five weeks before my graduation for me to descend to Case Library’s second floor archives, reshaping my understanding of myself and this University.

There is something inherently anthropological in sifting through dusty manila folders, even though they existed beyond my neither neutral nor necessary presence. Even if we resist it, the act of archival “discovery” carries colonial and privileged undertones; I am engaging with documents that demonstrate lived experiences that were never mine. Simultaneously, the very existence of these records is a testament to the labor of those who preserved them, ensuring that these histories are not forgotten or erased.

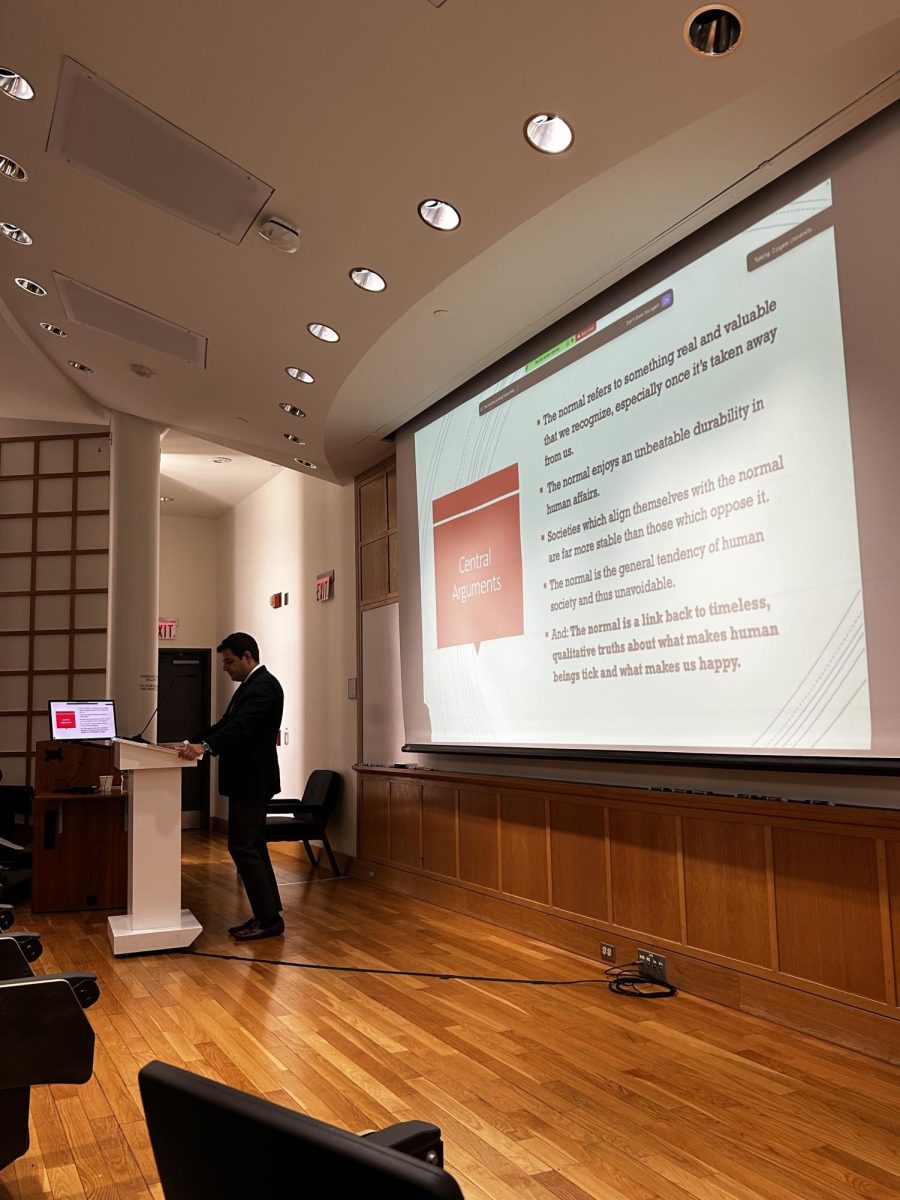

In the case of the difficult work of political protest, feelings of exclusion and marginalization cannot be entirely encompassed in a material manner. However, we are lucky enough at Colgate to at least maintain a semblance of documentation, and in my thesis hive mind, I sought out written, material information in every manner possible. One of the most striking materials I came pictures of student protestors holding signs that encapsulated the intensity of the 2014 sit-ins. I also examined the The Colgate Prism, later referred to as the Prism Magazine, a publication devoted to advancing diversity — specifically looking at the February 1987 issue celebrating Black History Month, the 1996 edition that reflected on first-year student experiences and a contentious 2002 piece by Professor of Political Science Barry Shain criticizing the “feminiza-tion” of Colgate’s faculty and the “destruction of the fraternities.”

The poster and photograph are from the 2014 Association of Critical Collegians’ (ACC) organized sit-ins on campus, catalyzed by a series of racist comments made on the anonymous social media app YikYak. The ACC was created to foster a “culture of inclusivity” at Colgate. According to the Global Nonviolent Action Database, some of these comments included, “White people won life, Africa lost, sorry we were so much better than you that we were literally able to enslave you to our will” and “I chose Colgate for the lack of it’s diversity. I knew the statistics. It’s not my fault you didn’t read the fine print.”

When I briefly spoke with the former ACC members last fall, they shared how deeply the experiences of racism on campus affected their mental health. The YikYak posts represented a breaking point for students of color. In one of the most painful moments of their struggle, some of the women even discussed how they had contemplated a suicide pact, highlighting the profound mental health toll of exclusion and racism on campus. To me, this served as a haunting testament to the psychological toll of cultural exclusion on campus, with legacies that persist today. Their advisors were able to shift their course of action, transforming their sense of isolation into a moment of reclamation. Even as a senior, I felt rattled by how recent and upsetting these histories are and the extent to which we cannot access this holistic understanding of the past from only documents and images.

Yet, rather than rejecting the archive outright, I hope to approach it with an awareness of its gaps. There is a privileged component of tangible access that permitted me to fully comprehend how lucky I was to feel a degree of safety and comfortability on this campus. I felt grateful for the students who came before me and did the work for me to, ironically, complain about the contemporary unequal conditions on this campus. However, the stories of the 2014 sit-ins still extend far beyond the materials stored in Case Library. As long as we can engage with the archives as outsiders seeking to capture what remains unrecorded, we can fully appreciate their value. While this is not a novel assertion, the act of “gazing” in itself can be a neocolonial practice in which we situate ourselves in a practice of hierarchical categorization. I now hope to turn to other knowledge forms I hadn’t explicitly identified as potential methodologies in my own academic research because they are not hegemonically normative.

Returning to my previous notion of journeying up the Colgate hill, this campus was never something I could claim or map singularly. If anything, examining tangible materials of its important past of protest has enlightened me to its lack of physicality and how it functions in entirely political, social and immaterial planes of existence. Colgate is not just a physical space but exists in protest chants, the radio waves of WRCU FM 90.1 and even the ever-present scent of cow manure that disappears and reemerges upon increases in temperature. I could “leave my mark” here in some cliche way, but like the women of the 2014 sit-ins, I hope my actions will outlive their singular moments, resisting the bounds of the file cabinet.