We Are All Related

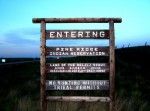

I was born in a well-off county, in a relatively wealthy area of the nation. This past spring break, I was given the opportunity to travel to the second poorest county in the United States with the COVE. When I told my family members and friends I was going to the Pine Ridge Reservation, located in South Dakota, they seemed perplexed. “Why would you want to go there?”, they asked in confusion. Pine Ridge is depressing; Pine Ridge is full of poverty; it’s not … fun, they explained. You should save up and go to Florida instead.

Contrary to what the doubters proclaimed, my trip to Pine Ridge was one of the best experiences of my life. Don’t get me wrong – it was hard work, and at times emotionally exhausting. There were instances when I felt in over my head and overwhelmed by the pressing issues surrounding me, which I could not ignore. Yet, at the same time, being on the Reservation gave me an incredible sense of calm and happiness. It is impossible to pinpoint a single source for these feelings. Maybe it was the early-morning wake-up calls which started every work day, or sleeping in a room with six other people who shared the same excitement I had to be at Pine Ridge. Maybe it was the five children who lived across the street from our work site, who shyly introduced themselves and asked us to play with them, to which we eagerly obliged. Maybe the sense of happiness and calm I felt came from Sheila, one of the children who wowed me with her adorableness and energy. Or, maybe it was from Kiona, her slightly older cousin, who begged for countless piggy-back rides which I couldn’t refuse. Maybe it was from Clarence, the oldest of the bunch, who told hilarious “Yo Mamma” jokes and was eager to help us paint a propane tank robin’s egg blue.

But maybe the way people feel when they come to Pine Ridge is from more than just the incredible individuals they meet there. Maybe it’s from the enduring sense of hope the Reservation exudes. Despite the statistics, despite the crippling history of past transgressions against their people, the Lakota nation is optimistic for their future. There is a sense on the Reservation that no matter how hard life seems now, things will get better.

Whether or not you have been to the Reservation, we as American citizens owe the Lakota solidarity in their perseverance towards a better future, which includes amending our historical wrongdoing. Our government should apologize for the Massacre at Wounded Knee, and should reconsider the Congressional Medals of Honor it awarded the U.S. 7th Calvary, who slaughtered more than a hundred innocent Lakota men, women and children. Our history textbooks should not gloss over or condense Native American history into a single-day topic that is breezily discussed in high school classrooms. And the people of our nation should start a campaign to rename Custer State Park, so that this sacred Lakota spot in the Black Hills celebrates not an armed killer, but Lakota heritage and culture.

It is simple fact that we can no longer ignore the United States’ wrongdoing, or turn our backs on people of Pine Ridge. When I was on the Reservation, the expression Mitakuye Oyasin was repeated constantly, and for good reason. Its translation: We are all related.