Starving for Perfection

Junior Emily Richards*, a petite blond dressed in sweatpants and a baggy Colgate sweatshirt, sits curled up on a couch in her apartment. Clutching a cup of tea, she unwittingly displays the scars on her right hand, permanent reminders of a compulsion from which she’s – tenuously – freed herself. She used to inadvertently scrape her knuckles, she explains, because her teeth would gnash against her skin as she stuck her hand down her throat to gag herself.

Richards is one of approximately eight million Americans – 90 to 95 percent of whom are women – who suffer from eating disorders. She has worked to overcome both anorexia nervosa, characterized by self-starvation and excessive weight loss, and bulimia nervosa, an often secretive cycle of binging and purging through vomiting, excessive exercise and/or laxative abuse. One can hardly underestimate the seriousness of the consequences: bulimics can develop heartbeat irregularities from vomiting and laxatives, and anorexia is fatal for 20 percent of its victims. Richards knows how lucky she is that the only lasting physical reminders of her illness are scarred knuckles.

According to a study published earlier this year in the Journal of Counseling and Development, mental health professionals have long debated over two modes of conceptualizing mental illness. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) – which contains the criteria used to diagnose mental illness – defines eating disorders categorically. That is, the DSM delineates anorexia and bulimia as the primary eating disorders, with a third category for combinations of symptoms that may or may not constitute diagnosable eating disorders. Some experts maintain this perspective, according to the Journal of Counseling and Development, viewing mental illness as a “set of categorical (i.e., qualitatively different) disorders, distinct from normal development and from each other.”

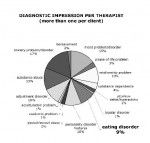

But lately many researchers and clinicians – including Colgate’s Director of Counseling & Psychological Services Mark Thompson – have begun to assess mental disorders as “dimensions occurring along a continuum on which individuals vary in degree but not in kind.” In other words, perhaps eating disorders fall at the extreme end of a range of eating behaviors which, according to Thompson, encompasses everything from “body image dissatisfaction – maybe behaviors that are troubling and interrupt a student’s regular routine – to the extreme end of the continuum, something that would qualify as an eating disorder.” In the counseling center’s annual compendium of statistics related to the treatment of Colgate students, perhaps the most startling figures are those detailing therapists’ diagnostic impressions of their patients. That is, Conant House’s therapists tallied the numbers of students falling into each diagnostic category, often filing a student under more than one. Eating disorders, prominent as they are on Colgate’s campus, only account for nine percent of the problems treated, which suggests that disordered eating is often symptomatic of some other, overarching illness – such as anxiety or depression, the top two psychological disorders Colgate’s counselors treat. Therefore, part of the reason Thompson and his colleagues believe in the effectiveness of the continuum approach is because they have treated numerous students with problems that manifest themselves in terms of food but that have roots in issues more complex than a simple desire to lose weight.

It’s important to sort through these issues because statistics indicate eating disorders are epidemic among college women and are on the rise among men. In February 1998 approximately 600 college campuses participated in a National Eating Disorders Screening Program; of the 26,000 students who filled out questionnaires, 4,700 were referred for treatment for serious eating disorders. A study in the Journal of American College Health, published in the same year, reported that about one quarter of the female undergraduates surveyed felt they were not in control of their eating habits. Therefore, even though about 10 percent of the general population of women suffer from diagnosable eating disorders, that figure jumps to anywhere from 18 to 25 percent among college women.

According to Thompson, eating disorders rank among the most difficult mental illnesses to treat. Experts can’t pinpoint a single cause for anorexia or bulimia, and, according to researcher Sheila Lintott, “behind any eating disorder there is likely to be a complicated web of social, familial, psychological or biological determinants,” even in a single individual. We probably aren’t wrong to blame eating disorders on the preponderance of media images of dangerously underweight female bodies, the intense pressure on women to conform to narrow definitions of beauty, or our culture’s idolization of the celebrities who embody those standards. But if we hope to understand the mysterious and dogged determination with which millions of eating-disordered people systematically starve themselves, we must appreciate the complex intersection of these and other forces in the psyche of the contemporary young woman.

Karen, Calista & Mary-Kate:

The Cultural Obsession with Eating Disorders

“The beautiful is the symbol of the morally good.”

– Kant

The existence of eating disorders was propelled onto our cultural radar in 1983 when singer Karen Carpenter starved herself to death, at which point a magazine cover reported, “Carpenter Dies of Anorexia Nervosa – A Rare Mental Disease.” In photos taken during the final weeks of her life, Carpenter looked emaciated and frail, and she could barely walk or hold up her head. In the same magazine, on the very next page, was a liquor advertisement featuring a model in a white bikini, sprawled out and sexually provocative – but her body looked a lot like Carpenter’s.

According to Mary Pipher, Ph.D., author of Hunger Pains: The Modern Woman’s Tragic Quest for Thinness, “We are living in a culture that promotes a monolithic, relentless ideal of beauty that is quite literally just short of starvation for most women.” Recent psychological research indicates that virtually all American women are ashamed of some aspect of their bodies; moreover, 90 percent of women overestimate their body size. Pipher recalls an evening spent talking with a friend, Sandra, over wine and cheese: “Every time she had a slice of cheddar, she interrupted her conversation to comment, ‘This will be my last’ or ‘I feel evil tonight.’ Sandra was not an exception. Like most of us, she’d been socialized to apologize for her appetites. Food was her enemy. Her body was her enemy. To enjoy food was to sin.” The American woman’s paranoia about weight manifests itself in the diet support groups, dangerous weight-loss drugs, and the low-calorie and low-carb industries that flourish in America; we give billions of dollars to those who can incite the fear of weight gain and promise to help.

Richards speculates that one of many influences that may have contributed to her eating disorder is the fashion industry. “I read a lot of fashion magazines,” she comments. “I’m interested in something that’s very concerned with looks, and it makes me more concerned about my appearance.” The images in those magazines, of course, are often digitally altered; what’s more, the women in the photographs often struggle with eating disorders – a phenomenon the media has dwelt on nearly as much as the women themselves. Celebrities like Paula Abdul, Kate Beckinsale, Jamie-Lynn DiScala and, most recently, 18-year-old Mary-Kate Olsen have admitted to their much-publicized struggles with eating disorders, and it’s hard to forget the torrent of media speculation a few years ago about the bony bodies of Calista Flockhart and Lara Flynn Boyle.

Some suggest there’s a competitive dimension to women’s weight that accounts for our near-obsession with the eating habits of high-profile celebrities. “With bulimia it’s like, it’s not fair,” Richards remarks, explaining the mindset of a bulimic. “Why does everyone else get to eat cookies and not gain weight but I can’t? It’s like, with bulimia, I can eat this cookie and – look what I can do – I can get rid of it. Look, guilt-free, in your face! I can lose weight even though I’m eating all this s**t, and you can’t.” As long as people didn’t know Richards was purging, her ability to eat and still remain slim was a source of power that made her the envy of others.

The association of food with morality – and the consumption of food with transgression – permeates our culture, perhaps due to the perceived link to self-control Richards points out. Those of us who have failed in our dieting – thus proving ourselves shamefully lacking in self-discipline – savor the revelation that a famous, beautiful woman has an eating disorder because it proves that she too must suffer for her looks. “When our culture puts someone up on a pedestal so much,” senior Lauren Findley observes, “you kind of want to knock them down a little bit. You want to be able to say, ‘Oh, but she’s anorexic.’ You want to know that she has a problem, a mental illness, that she’s messed up – and that makes you feel a little better about not being as skinny as she is.”

The goal, then, is contradictory, and impossible for the vast majority of women: we must be exceedingly thin, but naturally. “On the whole, guys are attracted to thin girls,” senior Adam Roth remarks. “I think a lot of that is bred into us, because that’s what we see, and that’s what we’re told to like. And even though guys want that, at the same time you don’t want the baggage – emotionally and socially – that comes with an eating disorder.”

It appears there exists in our society a fine line between the woman who merely restricts her food intake – a practice our culture considers commendable – and the eating-disordered woman, who we denigrate. Pipher recalls the public’s reactions when she first started giving talks on her experience treating eating disorders. A television reporter asked her whether she knew that Jane Fonda was “guilty of bulimia,” and people in the studio approached her afterwards to say things like “Bulimia sounds disgusting.” In other words, the reason eating disorders are a source of shame for many sufferers is that – as opposed to the dieter, who controls her eating – the woman with an eating disorder is controlled by her disease. The catch-22, then, is that the thin but eating-disordered woman is little more admirable than the woman who is not thin – even though, for most women, meeting culturally inculcated standards of beauty requires near-starvation.

Living Inside A J.Crew Catalogue:

The Pressure to be Thin at Colgate

“Hunger hurts, but starving works,

When it costs too much to love.” – Fiona Apple

Richards’ troubled relationship with food began during her sophomore year of high school when she dieted to lose weight. The diet worked for a while, but her weight continued to fluctuate throughout high school. After her first semester at Colgate, she “didn’t want to go home fat” for winter break. “I thought, ‘what would happen if I threw up my food?'” she recalls. She took to “working out like crazy and never eating – or when I did eat, I’d throw it up,” behaviors that became easier to keep up her sophomore year, when she lived alone and could more easily conceal them from friends.

It didn’t help when Richards was denied a bid from her first-choice sorority, a blow to her already shaky self-confidence. “It’s really tough here [at Colgate] because everyone is so good-looking,” she explains. In Richards’ mind, at the time, her looks had caused her sorority rejection, as well as her general discomfort with the Colgate social milieu. “I thought guys would want me to be really thin,” she says. If only she were thin, she thought, “I’d look better in my clothes. I thought I’d be more accepted if I were thinner and better looking. I’d have more friends. I had all these terrible ideas, and it really killed me; I was horribly depressed. I only cared about what I ate, how I looked, if my clothes were getting bigger on me.” She had lost so much weight by Christmas that her parents realized she needed to leave school for a semester to get medical help.

Richards’ five-month treatment program, which took place at a well-known New England eating disorder clinic, consisted of five days a week of talk therapy combined with nutritional education. She says one of the most grueling parts of treatment is that the counselors “make you eat dinner with them, and you have to eat everything. Oh, that’s hard. You could be like, ‘No!’ and you could cry as much as you wanted, but they’d still sit there with you and make you eat it.” Richards graduated from the program last May but continued nutritional therapy throughout the summer.

But Richards harbors no pretenses of having fully recovered, and she realizes being back at Colgate makes her struggle more difficult. “My psychiatrists are worried about me being back here because they know it’s so tough here,” she says. And she’s not alone in finding Colgate a difficult environment in which to maintain a healthy body image: “There were like four other Colgate cars at [the eating disorder therapy clinic] when I was there.”

It’s unlikely that the incidence of eating disorders at Colgate is much greater than at other small, elite colleges. But it’s hard to deny that many Colgate students feel an unusual degree of pressure to look good. Findley says she’s “a loner in my apartment because I eat carbs.” Roth surmises that “On a campus like this, where you have a lot of well-off kids who have the resources and the ability to go to the gym, lead active lifestyles, eat healthily, have confidence, have all kinds of nice things – those kinds of people probably perceive themselves to be more attractive than the rest of the population, whether that’s true or not. So in a place like this,” he continues, “I think you’ve shifted the entire scale up, and so the tendency is for people to be more competitive about those things.”

Richards agrees, pointing out that “Going to the gym here is hard. It’s totally competitive. When I’m at the gym, I have to go twice as hard as the person next to me.” For Richards, as, doubtless, for numerous other Colgate students, the degree to which she could maintain her weight was an important means of expressing self-worth. “My mindset was like, ‘I’m doing really well here. I’m really thin here; I look great.’ Everyone’s going to think I have great self-control. I thought if I could keep my weight down, that was the one thing people could accept me for, no matter what.”

But is the association of thinness with social acceptance really accurate? Richards insists that “your appearance determines who your friends are here. I’m not friends with the people I really would want to be friends with. If I could have my choice, I’d be friends with the tall, skinny, blond girl. You just feel like [attractive people] are accepted more. And they are, I’m telling you. You can tell.” According to Richards, a person’s looks trump all other qualities when it comes to determining her social success at Colgate, particularly when it comes to her attractiveness to guys. Regardless of whether that’s true, Richards says she’s “always going to have the idea that being skinny is what they want.”

But according to senior Scott Wallace, Colgate women often overestimate how thin they need to be to appeal to men. “Weight is not the defining aspect of a girl’s attractiveness,” Wallace insists. “Sometimes girls don’t realize how important it is to be confident. People read a lot into confidence: when someone’s confident, you kind of assume that person has something to be confident about. A natural self-confidence – and just having your head on straight: girls underestimate the importance of that more than anything else.”

Put that way, one wonders whether social acceptance at Colgate might really be less about how a person looks than about how a person conducts herself according to how she feels she looks. “I always feel as if I’m below everyone,” Richards admits, “and maybe that’s because I feel inferior in my looks. Sometimes I don’t want to go out, because I feel really fat and I just want to stay in. I also wear really baggy clothes a lot. Right now I’m living in these huge, baggy jeans that I have. I think tight jeans make my legs look huge, and I don’t want people to look at me and say, ‘She has a huge ass; what is she wearing?’ And my stomach’s so huge, I need a big sweatshirt to cover it up.”

It’s hard to comprehend that such self-denigrating thoughts regularly haunt Richards, a pretty blond with large blue eyes and a petite, muscular body, like a gymnast’s. Even though undergoing therapy has taught Richards to force herself to eat healthily most of the time, she admits that “all the same exact fears” about her weight still trouble her. “It’s so hard,” she affirms. “I’m better now, but every day I still want to stop eating or throw it up because I feel like I’m getting fatter, and everyone else still looks good.”

Richards’ experiences are consistent with national statistics that estimate one-third of people treated for anorexia experience a relapse. Recovering from eating disorders is lengthy and expensive: a recent UCLA study found that the median recovery time from anorexia is seven years, during which time a patient’s care can run up an estimated $150,000 in medical bills. Richards has considered going to Conant House to continue her therapy but hasn’t yet: she says Colgate’s counselors “know their stuff” but claims they’re not equipped to adequately support someone with a full-blown eating disorder. According to William Davis, a vice president of the Renfrew Center, a private eating disorder clinic in Philadelphia, colleges “have to make choices about how they use funds: for education on drug and alcohol abuse or date rape or eating disorders.” But if Richards is correct – if the social climate at Colgate is as destructive as she believes it is – then there probably isn’t much Conant House can do to ameliorate the situation. Moreover, research shows that a cultural obsession with thinness isn’t the only factor contributing to eating disorders.

Sophomore Amy Mastrocinque remembers the exact moment she began to struggle with anorexia. While she had always dealt with the typical self-confidence issues most adolescents face, her eating disorder was triggered when her father was diagnosed with brain cancer while she was in high school. “It was right around that time,” she recalls, “when I was eating a sandwich for lunch one day, and I just looked at it and thought, ‘I’m fat.’ And I threw it away.” Mastrocinque continued to severely restrict her food intake, and “it became an ugly spiral. I stopped eating meat, dairy, bread. All I ate were fruits and vegetables, and before I went to bed I would drink a huge glass of water, just to fill my stomach, because I was so hungry.”

Mastrocinque realized the seriousness of her condition when she became so frail that her cheerleading coach prohibited her from participating in stunts. In addition, her concentration in school started to suffer, so she decided to gain some weight in a healthy way. The decision was necessary but extremely difficult: Mastrocinque remembers shopping for clothes and “wearing a size two and thinking, ‘Oh my god, I’m so big.’ Because I was used to wearing a double zero.” But the fact that her father’s cancer had gone into remission helped give her strength, and she maintained a healthy weight for a while.

Like Richards’ illness, Mastrocinque’s disorder relapsed, but for different reasons: Mastrocinque’s father, who worked in the north tower of the World Trade Center, died in the September 11 attacks. In the months following the tragedy, Mastrocinque “got really depressed” and found herself turning to food. “I remember eating just to make myself feel better,” she explains. “I would eat chocolate, chips, everything, and feel so sick after. And that’s when I realized I could throw up. That started a whole new cycle.”

Mastrocinque knew she couldn’t go away to college if her bulimia persisted – and she was also aware that her illness was devastating her mother and brother, who had already endured so much tragedy – and she managed to summon the willpower to recover. “It was a really slow process, finding healthy ways to eat and fighting the urge not to,” she recalls. “There were times I would just sit there and cry because I’d eaten something and wanted to throw it up so bad. But I just knew I couldn’t; it was hurting my family so much.” Because Mastrocinque’s disorder was so closely tied to her emotional state, counseling and antidepressants aided in her recovery.

Though Richards’ and Mastrocinque’s eating disorders seem to have had different causes, one symptom the two women shared was a severely distorted body image. In a high school photo, Mastrocinque’s prom dress reveals bony arms and protruding ribs; though her friends and family thought she looked emaciated, Mastrocinque recalls, “I thought I looked great. It was a rush. The rest of my life was a mess, but I was controlling this.” Similarly, Richards insists, “I don’t want to look healthy; I want to look borderline disgusting, like a skeleton. I used to have this thing where if I could see my bones, that was awesome. If I could stretch and see my ribs, that was great. Or if my hip bones stuck out. I liked that; it made me feel really good.”

But even most eating disorder sufferers agree that there is nothing attractive about a woman whose ribs and vertebrae protrude grotesquely, who grows a fine layer of fur all over her body because it doesn’t get enough calories to heat itself, who vomits so frequently that her eyes are bloodshot, her cheeks are puffy, and her hands are chapped and bleeding. Indeed, Richards admits that once her eating disorder progressed to a certain point, her continued desire to look emaciated had less to do with her appearance than with having “proof that I’m not fat.” Mastrocinque, moreover, developed an eating disorder in response to a traumatic event in her life; for her, weight loss was an afterthought. Something beyond the desire to meet cultural standards of beauty must contribute to eating disorders, since many sufferers starve themselves to degrees they know have nothing to do with what society considers beautiful.

Hunger for the Sublime

“You have a full-fledged eating disorder: anorexia nervosa with bulimic tendencies (or vice versa). The really shocking thing is that you have never felt so alive and invigorated, have never before lived so purposively. Today brings the cherished opportunity to revel in the sublime hunger to which others succumb. You feel this way, despite the fact that it is only a matter of time until your disordered eating makes an invalid, or corpse, of you.”

– Sheila Lintott, “Sublime Hunger”

Much has been made in recent years of websites that offer tips and support for those with anorexia and bulimia. Eating disorder sufferers who feel ambivalent about the prospect of treatment often use the terms “Ana” and “Mia” – short for anorexia and bulimia – to describe the diseases as well as the people they afflict. Typically created by and aimed at teenagers and young adults who suffer from eating disorders, Pro-Ana and -Mia sites – which often explicitly state that non-eating disordered people are unwelcome – offer a safe haven where “Anas” and “Mias” can commiserate and share advice in a non-judgmental forum. While many such sites have been forced off the web by nervous internet service providers wary of risking responsibility for, as America Online spokesperson Andrew Weinstein puts it, sites that “fall into the category of promoting physical harm to others,” a number of them still exist and are updated regularly.

Critics like Weinstein, perhaps rightly, insist that the existence of Pro-Ana and -Mia sites allows eating disorder sufferers to reinforce one another’s unhealthy eating styles, thereby perpetuating the epidemic of eating disorders that plagues much of the western world. The creator of a site called Help Me Ana explains on her home page that she has begun treatment and will no longer maintain her site. The announcement prompted complaints on her message board, including one from someone using the screen name “witchyfingers”: “HAH recovery, u r jus like the rest of them, u tune in & cop out wen it gets tough, i hope ur happy wen u get fat & hideous. Ana loved u & ur rejecting her 2 join the obesians.”

When an Ana or Mia defends her disorder as a “lifestyle choice,” rather than a diagnosable illness, in reality she’s probably grappling for control over a disease which, on some level, she knows controls her. In another sense, though, an eating disorder is a lifestyle: victims of full-blown eating disorders are consumed by their illnesses – Thompson says the typical anorectic or bulimic spends an estimated 80 percent of her waking hours thinking about food and weight loss – and eating-disordered people often continue their attempts to manipulate and control their bodies long after they have attained their desired weight. According to an article by Sheila Lintott published last year in the journal Hypatia, women’s desire for excessive thinness has partly to do with the pursuit of a sort of Kantian sublime experience.

In his Critique of Judgment, Immanuel Kant explains sublime experience as the profound pleasure one can attain in the apprehension of one’s privileged place in nature. One way we experience the sublime is through natural objects with an abundance of power, such as violent storms, erupting volcanoes, and the rough tides of the ocean. We know we would be physically powerless to defend ourselves if confronted with these forces, which is why they incite fear. However, as Lintott explains, “Kant proposes that the consideration of fearsome natural forces can cause us to realize our strength – not our physical strength, but rather, our strength of spirit. If we are in a safe place, the object is fearful, but not sufficiently so that it warrants retreat. If so, we may revel in the moment, taking pleasure in our ability to do so.” Our ability to contemplate and savor the fearsome “allows us to see that there is something in us that transcends the dominion of nature.”

We call certain objects sublime, then, not because their power arouses fear, but because the desire to defeat that fear calls forth our strength. According to Lintott, “we realize not that the object is sublime, but rather that the sublime resides in our own selves.” Sublime experience, then, is about gaining self-knowledge – the knowledge that we can “transcend our natural inclinations, and if need be, resist them entirely.” Kant says the sublime “keeps the humanity in our person from being degraded”; in other words, sublime experience teaches that a part of us is free and worthy of respect – that we, as humans, are superior to nature and its laws.

Human beings have certain natural, animalistic needs, one of which is nourishment. We must eat to survive, and, in a society in which food is abundant, we eat for pleasure and comfort even after we have satisfied our hunger. Our culture exalts people who successfully diet – who succumb only to the desire for food based on need and resist the desire to eat unnecessary food, despite the pleasure it might involve. Lintott therefore concludes that “it would take an abundance of strength to overcome the desire for food to the extent that one avoids not only unnecessary calories but virtually all calories. This is what the eating-disordered individual attempts to accomplish.” The anorectic does so by refusing to eat; the bulimic devises a plan by which she can enjoy the pleasure of eating without satisfying the actual physical need for food. This interpretation could explain why some bulimics find both binging and purging pleasurable experiences. “The only thing that could make me feel better was eating and then throwing up,” Mastrocinque explains. “It was kind of therapeutic for me in a weird way, because it was like I was throwing up all the bad feelings.”

In her 1993 book Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body, Susan Bordo suggests that hunger is a defining feature in the life of an eating disorder sufferer. “Anorexic women,” Bordo explains, “are as obsessed with hunger as they are with being slim. Far from losing her appetite, the typical anorectic is haunted by it.” Without her appetite, in other words, an anorectic’s attempts to triumph over it would be meaningless. Women with eating disorders are, no doubt, extremely concerned with their outward appearance, but Lintott posits that’s because their bodies serve as symbols of their inner strength. Perhaps Richards misses her protruding ribs and bony hips, not because she thought other people found her skeletal frame attractive, but because her body served as proof of her triumph of will over her hunger. Forcing herself to eat now is difficult partly because the ensuing weight gain means she no longer has those visible bones, but also because it eliminates the appetite, simultaneously terrible and sublime, that would allow her to prove her strength.