“Far From Vietnam” Remains Pivotal in Anti-War Cinema

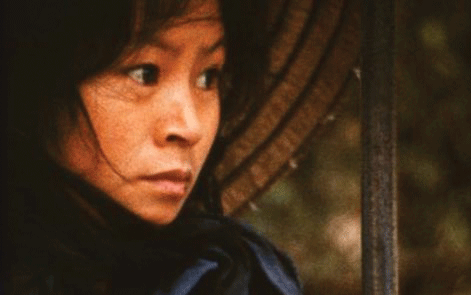

Film Evening: “Far From Vietnam”

A screening of “Far From Vietnam,” cosponsored by the Art & Art History Department and First-Year Seminars, swept the audience onto bomber missions and into the war-torn landscapes of 1960s Vietnam on Tuesday, September 18. Now considered an epitome of anti-war cinema, “Far From Vietnam” was once ostracized by the majority of Americans and considered communist propaganda at its first screening at the New York Film Festival in 1967.

Aiming to reflect the sociopolitical and geographical components of the Vietnam War, “Far From Vietnam” showcases contrasting aesthetics from eminent New Wave filmmakers such as Alain Resnais, Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Lelouch and Joris Ivens into a unified documentary. Chris Marker, who was at the creative helm of this collaborative production provides the voiceover. The film contains footage of war-torn Vietnam and anti-war protests in New York, providing sociopolitical context to the conflict and monologues characterizing the identity struggle of French intellectuals in the resistance of the war.

At the crux of the movie is William Klein’s footage of protesters and counter-protesters lining the streets of New York. The pro-Vietnam protesters, consisting of mostly minority activists and advocates, were joined by New York Mayor John Lindsay. A few days later, they were met with intense opposition at Wall Street by rowdy screams of “Bomb Hanoi!” and “Go back where you came from!” When questioned, most people did not know what “napalm” meant, which indicated naivety about the dangers Vietnamese people faced.

Furthermore, Klein adds emotional weight to the film when he sets up an interview with Ann Morrison, widow of Norman Morrison, a well-known protestor of the Vietnam War. Klein captures Morrison’s grace and calm when she describes her husband’s martyrdom upon burning himself alive in front of the Pentagon in 1965. The clip was adorned with heartfelt messages from Ann Uyen, a Vietnamese woman living in Paris, about the significance of his heroic act.

Jean-Luc Godard, whose monologue lends the movie its title, comes into the center of the camera frame in his directed segment. Laden with snippets from other Godard films, this portion of the film validates his claim that he “puts Vietnam in every film.” In his monologue, Godard also reveals his unsuccessful attempt to travel to Vietnam and his growing resistance against the “economic and aesthetic imperialism of the American cinema.” In this particular scene, the audience could see the futility Godard endures in his questioning of reality, so much so that he exclaimed, “let Vietnam invade us” in order for people to see the role Vietnam plays in their lives.

Later in the film, Alain Resnais’ sequence showed viewers the bigger picture of world affairs in which anti-Americanism and anti-totalitarianism sentiments grew stronger, culminating in the statement that “the Americans are the Germans of the Vietnamese.”

The complex storytelling was not lost on attendees. “What I found really interesting was the metaphor of war-torn countries being in a stock market where they are pitted against one another to compete for people’s sympathy, said first-year Minh-Khue Nguyen, who is from Vietnam. “The movies felt disruptive at times, with footages intercutting each other, but in the end, it all builds up to a common theme and ideal. The message about solidarity was very clear, and though the film is old, it has not lost any relevance,” Nguyen said.

Contact at [email protected].