Black Bodies, White Tears

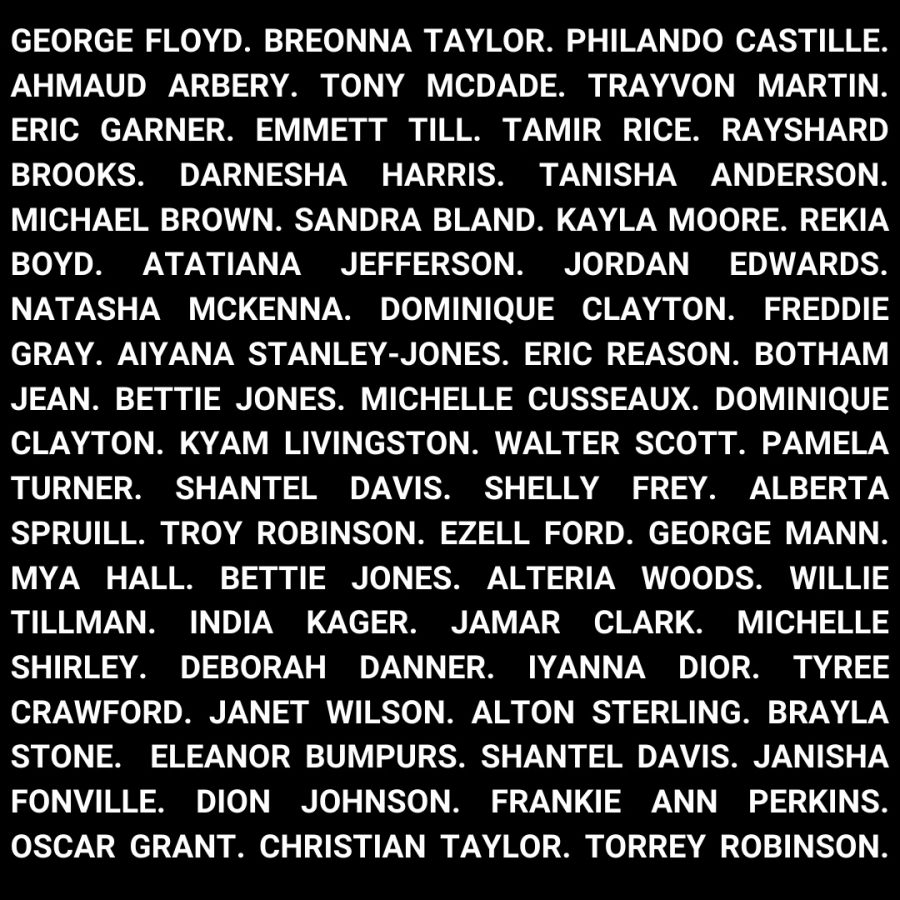

It has been over a month since George Floyd’s untimely death at the hands of a white police officer who knelt on his neck for nearly eight minutes, ignoring sounds of Floyd’s obvious distress and relishing in an egregious but familiar show of state-sponsored violence.

In the days, weeks and now months that followed Floyd’s death, protests and unrest swept through all 50 states like a second pandemic, an unprecedented display of political mobilization that found its way to even the smallest, whitest, most conservative corners of the nation. The scale and breadth of this social movement can largely be credited to the historically consistent efforts of Black youth, who have remained at the heart of grassroots activism since the Civil Rights Movement.

The acknowledgement, no matter how passive, of the once radical notion of Black lives possessing value, is a relatively new phenomenon for many of the outer suburbs and small towns where these protests have emerged. In fact, a recent Pew Research Center poll found that 67% of Americans support Black Lives Matter, a significant increase from the movement’s conception in 2013, when a majority of the nation’s voters expressed their opposition to the movement and its arguments. Evidence points to a leftward political shift amongst the youngest constituents of these homogeneous regions.

But more than their waning allegiance to conservative politics, the ease with which young, educated white Americans have replaced links to their carefully curated social media profiles with resources to support the Black Lives Movement is indicative of a larger, less surprising trend in American history. Simply put, the conscience of white America is intrinsically tied to a not-so-secret fixation on Black trauma and Black death.

For as long as human rights abuses and systemic racism have been elements of America’s relationship with Black people, there have also been Americans who staunchly deny the existence of such inequities. During the perennial era of American slavery, these naysayers rationalized the reprehensive institution with anti-Black pseudoscience, stories of benevolent slave owners, and arguments concerning the economic benefits of trading and enslaving humans.

Later, with the shameful fall of the Confederacy and slavery’s abolition behind them, the nation embarked on a rebuild that brought the introduction of Black codes and organized violence which threatened the labor and lives of African Americans. Again, white Americans rejected Black Americans’ allegations of mistreatment, arguing that freedom from enslavement had simultaneously granted them freedom from oppression.

This trend of white America’s justification and ignorance of the brutal marginalization of Black Americans continued into the Jim Crow Era and the post-Civil Rights Act period, where the codification of white supremacy allowed for beginnings of mass incarceration, voter suppression, employment and housing disenfranchisement, all of which remain fixtures in contemporary American society.

And throughout these historical moments of racial oppression, a population which civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr. famously referred to as the “white moderate” remained passively opposed to and subsequently passively in support of Black Americans’ strife. That is, until Black trauma and death arose as instruments of political awakening, forcing them out of their silent stupor and into hesitant vocality concerning racial inequality and discrimination.

In the antislavery writing of Lydia Maria Child and other white abolitionists, the use of the powerless, tortured body of enslaved Africans was a popular and graphic representation that exploited the society’s almost erotic fascination with pain and torture to spread antislavery messages in 19th century pamphlets. Previously swayed by the aforementioned defenses of slavery, it was often this voyeuristic spectatorship on brutalized Black bodies which forced all participants into a gross cloud of complicity, aiding in a shift in public opinion and later the abolition of slavery.

Without fail, the positioning of Black bodies as erotic objects of sympathy in order to ignite movements for Black liberation reared its head again during the Civil Rights Movement. Two famous examples of this phenomenon include the open casket funeral of Emmett Till, where the mutilated, rotting corpse of the 14-year-old African American was put on display for the press after the young boy was beaten to death by two white men for allegedly flirting with a white woman. The second example occurred years later with the televised records of the brutal repression of Black peaceful protestors across the South.

“We are here to say to the white men that we no longer will let them use clubs on us in the dark corners,” King said. “We’re going to make them do it in the glaring light of television.”

With both King’s activism strategy and Emmett Till’s mother, Mamie Till’s decision to hold an open casket funeral, there was a perspicuous understanding that because white Americans had spent decades denying the horrors of being Black in America, liberation would only come from undeniable images of violence inflicted on Black bodies.

Over half a century later, white America’s unquenchable thirst for the spectacle of the brutalized black body persists on both sides of the political spectrum. As Black Americans are killed at a disportionate rate by the police and their white peers, the availability of these lynchings on video has once again awoken another shift in American politics.

For far right Americans, the image of the beaten, broken and dying Black body functions as an indicator that their beloved systems of white supremacy are still alive, well and doing their job: dangling promises of equality in front of Black Americans’ noses as the boot of neoliberal capitalism and systemic racism presses their faces against cement until they bleed.

For self-proclaimed white liberals, these same images warrant meaningless self-flagellation, serve as material for contrived, self-serving think pieces on privilege and power and allow for swiftly rehearsed dance routines of surface level activism for their equally “liberal” peers. The result of these performative instances of white guilt and outrage is the same vision far-right white Americans’ hold for Black America, an unchanging outlet for white fear, white discontentment and white gratification.

So it is with warranted caution, latent resentment and tamed hope that many Black Americans approach this wave of social change that white consumption of Black trauma porn has helped to ignite this summer. Are white liberals’ participation in protests, public grappling with past transgressions and intake of anti-racist media a knee-jerk reaction to images of cruelty or rather an overwhelming want for equity across this nation? Are either sustainable vehicles of genuine structural change? When the revolution is not televised how will white allies hold themselves accountable?

Amarachi Iheanyichukwu is a senior from New York City concentrating in political science with a minor in creative writing. She’s previously served as...

Don Gibson • Jul 14, 2020 at 11:43 am

Great piece, Amarachi. The idea of ‘black trauma porn’ is startling to be sure. I too, even though I am old white guy, view the future with trepidation. I yearn for genuine change but hold little faith in this society’s ability to make it happen.