Steps in the Right Direction: NAGPRA at Colgate

Printed with permission of LMA

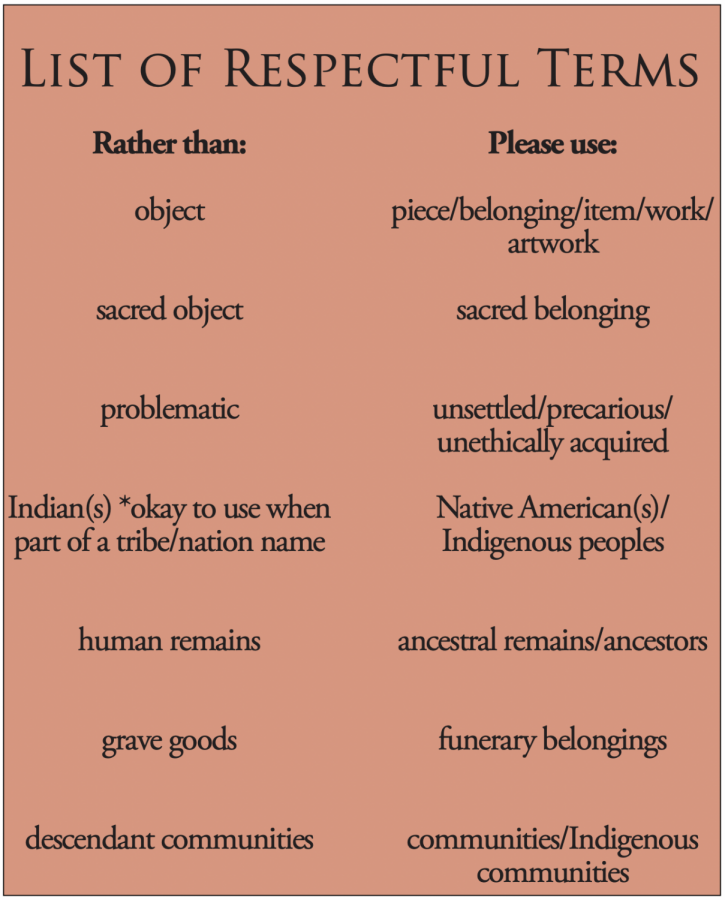

RESPECTFUL LANGUAGE: Compiled by LMA staff members Lisa Latocha and Kaytlynn Lynch.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) is a federal law passed by the U.S. Congress in 1990 which finally recognized that Indigenous ancestral remains and cultural items should be treated with respect and ultimately returned to the communities from which they were originally taken, as outlined by the Association on American Indian Affairs. Any U.S. institution that receives federal funds must comply with NAGPRA, which includes many agencies, museums, colleges and universities. Among those institutions is the Longear Museum of Anthropology (LMA) at Colgate University which was built on traditional Onyota’a:ká (Oneida) homelands and currently houses thousands of Native American belongings in its collection.

Co-director of University Museums, Curator of the Longyear Museum of Anthropology and Research Affiliate and Instructor in Sociology and Anthropology Rebecca Mendelsohn, along with other members of the LMA team, is directly involved in ensuring that ancestors and belongings are returned to their proper homes.

“NAGPRA is a law that was passed … after many years of Indigenous activism to address a series of human rights abuses. The Association on American Indian Affairs has been heavily involved with this work, from the passage of NAGPRA to its implementation today,” Mendelsohn said. “NAGPRA is an extremely delicate subject and one we take very seriously at the museum.”

Not all Native American belongings are subject to repatriation under NAGPRA. The law focuses on four categories: human (ancestral) remains and associated funerary objects (belongings); unassociated funerary objects (belongings); sacred objects (belongings); and objects (belongings) of cultural patrimony. Professor of Anthropology and Native American Studies Jordan Kerber, formerly the curator of archaeological collections at the LMA, explained in great detail what was meant by each classification.

“Sacred objects are defined under NAGPRA in an interesting way, because one might think that all [belongings associated with remains] are, by definition, sacred, but NAGPRA specifies … that ‘sacred objects’ refers to only objects that were used in ceremonial activities,” Kerber explained. “Objects [which] are referred to as objects of cultural patrimony … are objects that are so significant, that they weren’t necessarily owned by an individual person, but are representative of an entire nation or an entire tribe.”

Since NAGPRA was passed, Colgate has repatriated (or rematriated, in the case of matrilineal communities such as the Oneida Indian Nation) a number of different belongings from the LMA collections. Colgate’s first act of rematriation was in 1995, five years after NAGPRA was enacted. Ancestral remains and associated funerary belongings were returned to the Oneida Indian Nation, previously listed as Oneida Nation of New York.

Most recently, Colgate and the Oneida Indian Nation announced in July of 2020 that ancestral remains found in the Longyear collections were to be returned to the Oneida.

“We are grateful for the return of these remains and truly appreciate Colgate University for coming forward with this discovery so that our ancestors may receive a proper reinterment at our burial grounds,” said Oneida Indian Nation Representative Ray Halbritter, as quoted in an article published by the Oneida Indian Nation and Colgate University in July of 2020.

Most of the time, repatriation happens without much press coverage. Although this might seem like an oversight, it’s actually deliberate.

“This work is happening all the time behind the scenes here at Colgate. While it might seem like it is hidden or swept under the rug, failure to publicize the specifics of individual cases is often based on the desires of the band, tribe or nation with whom we are consulting or collaborating,” Mendelsohn said.

The Onyota’a:ká, Oneida Indian Nation, is one of Six Nations within the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, meaning “People of the Longhouse.” The Haudenosaunee Confederacy flag was first hung in Frank Dining Hall in 2018, a small step toward acknowledgement that was surprisingly delayed, considering that the first flags were hung in 2013.

Curatorial Assistant and NAGPRA Coordinator of the LMA Kaytlynn Lynch agrees, adding that it is time for more substantial steps to be taken.

“It is my opinion that as an institution built upon the traditional lands of the Onyota’a:ká — known as the ‘People of the Upright Stone’ and/or ‘Standing Stone and Oneida Indian Nation of New York’ — that Colgate does not do enough to recognize its own history. Some small first steps have been taken to right many wrongs, but when can bigger steps be made? [LMA Community Liaison] Lisa Latocha and Sierra Sunshine ’18 worked hard to get the Haudenosaunee Flag hanging in Frank Dining Hall in 2018, but when will this flag also be flown in a more visible space outside on campus?” Lynch asked.

Lynch is the daughter of Dick Lynch (Turtle Clan) and granddaughter of Norma Jean Fera (1934-2014, Turtle Clan). In addition to her curatorial work with the LMA and NAGPRA compliance, she is currently leading the Land Acknowledgement Working Group on campus. The group was started by staff members in July 2019 and was first led by former Program Coordinator of the Center for Women’s Studies Odette Marie Rodriguez.

“[Rodriguez] reached out to me directly prior to her departure from Colgate in June 2020, asking if it would be okay to transfer ownership of all Land Acknowledgement Working Group documents to me to then carry forward. I agreed, knowing that this important work must continue in some way on campus,” Lynch said.

The Land Acknowledgement Guide is starting to get traction on campus. Interim Provost and Dean of the Faculty and William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Geography and Environmental Studies Ellen Percy Kraly reached out in September to LMA staff members involved with the working group, seeking permission to distribute the guide to all Colgate division directors. The idea was to forward this information to all department chairs and program coordinators in order to increase land acknowledgement efforts across campus.

Before NAGPRA was passed, museums in the U.S. used collections as an excuse for keeping ancestors and belongings found in excavations, often for racist and harmful reasons.

“What many people don’t understand is that, in the early days of collecting for anthropology and natural history museums, the focus was on collecting ‘scientific’ specimens and preserving ‘dying’ cultures. The collection of the remains of marginalized peoples played a central role in the development of scientific racism. While these ideas are now widely discredited, museums must continue to address these painful legacies,” Mendelsohn explained.

Moreover, work with NAGPRA has made it even more obvious how little is being done to try to right these wrongs, as there is still much work to be done.

“This work I do for Colgate is extremely important, heartbreaking and long overdue. This is the 31st year of NAGPRA law and here we are still trying to return everything back to their rightful homes,” said Lynch.

Acknowledging that Colgate was built on Indigenous land is important because it is a step in the right direction — one that will hopefully lead to more healing. It is also necessary to remember that, in many ways, Native American wounds are still open. Despite legislative advances such as the passing of NAGPRA in Congress, Indigenous peoples are often actively harmed and forcibly displaced, to this day, by government-sanctioned actions such as the building of new pipelines and dams, according to articles published by The Conversation and Cultural Survival.

There’s also another barrier to qualifying for repatriation under NAGPRA — any tribe, nation, band or community which is not federally recognized has a much harder time qualifying for repatriation under NAGPRA.

“Today in the United States, there are [574] federally recognized tribes. … But then there are over 200 tribes that don’t have federal recognition, and so it’s very difficult for them, under NAGPRA, to pursue repatriation,” Kerber explained.

Federal recognition is, by definition, decided by the U.S. government. Given the long history of massacres and displacement, many Indigenous nations are unable to ‘prove’ their claims to their own lands and history in an American court of law. As a result, NAGPRA compliance falls short of providing rights to many Indigenous peoples. That being said, the staff at the LMA are committed to going above and beyond.

“While there are specific laws that govern the return of ancestors and belongings under NAGPRA, many institutions choose to go beyond the letter of the law with the collections that they opt to return and for various aspects of the rematriation/repatriation process. We attempt to do this here at the Longyear, though we acknowledge we still have a long way to go,” Mendelsohn said.

During his time as curator, Kerber had a similar mindset. He described a case from about a decade ago involving a set of ancestral remains which came from Marion County, Ohio. The remains of two individuals had been in the Colgate collection since the 1950s, and were acquired by the original organizer of the museum, John Munro Longyear III.

“I attempted to find a home for these human remains. I felt personally that it was inappropriate for human remains to be in museums if the individuals, when they were alive, did not give permission to have their bodies studied by scientists or to donate their bodies to science. And so I then consulted with a number of tribes — I wrote about 70 letters to tribes that could potentially claim these remains,” he explained.

Kerber’s work was further complicated by the fact that there weren’t any remaining tribes in Ohio, as they had all been displaced, so he tracked down Indigenous peoples that, at some point, used to live there. Eventually, Kerber was able to locate the tribe and begin the process of repatriation, which occured in October of 2012, in private.

“Remains that [are] returned [are] not simply ‘bone fragments,’ but ancestors, and it is important that we think of them not as museum specimens, but as people who were forcefully removed from their places of rest,” Mendelsohn added.

There are a few notable initiatives on campus which are setting new precedents for the future of Colgate’s relationship with Indigenous communities. In recent years, the Senior Honor Society (SHS) has planned events in collaboration with the Oneida Indian Nation. Last year, SHS hosted “13 Days of Education” during the two-week universal quarantine at the beginning of the Fall semester, which included a talk entitled “Decolonization Practices in University Museums” featuring LMA staff, among others, as panelists.

“Our [program] focused on anti-racism, consisting of events that mainly centralized the voices and experiences of Black and Indigenous communities. … We hope to continue the ‘13 Days of Education,’ making it an SHS tradition. … We aim to embody an anti-racist framework that informs our organizing and to incorporate an intersectional understanding of identities and oppression, with decolonization as a central tenet,” said senior Alex Tran, the president of SHS.

That same year, SHS removed its previous name, which was a word appropriated from the Kanien’kehá:ka Nation (Akwesasne Mohawk) language. A new name for the society has not yet been decided.

“[The name was] disrespectful to the Haudenosaunee and diminishes the spiritual significance of their historic accomplishment. … We feel it’s our collective responsibility to amend our past mistakes and provide reparations to the affected Indigenous peoples. … We are conducting research into our name and history through the Colgate archives,” Tran explained.

Another initiative, started by Kerber in 1995 when he was the director of Native American studies at Colgate, has resulted in over 25 years of partnership with the Oneida Indian Nation doing archaeological work. It started as a summer program, through which Kerber and Oneida youth conducted archaeological excavations in the Hamilton, N.Y. area. The problem was, since all excavations were conducted on private property, all belongings found were kept in the archaeology lab at Colgate, where they are housed today, since none of them are subject to NAGPRA.

“I then decided to approach the [Oneida] Nation to ask them … [to] continue this collaboration … on their territory, on sites that they owned … [and also asked if] they could fund the research. … They thought about this, and agreed to both. And so I continued between 1998 and then going through 2003 working with the nation … all of the objects that were excavated [were] cataloged at Colgate and then given to the Oneidas … anything found on land that they owned [was] turned over to them directly,” Kerber explained.

Kerber continued this collaboration through his Fall “Field Methods and Interpretation” courses, bringing Colgate students to Oneida land to excavate sites.

“All of the objects … just like in the summer, were cataloged, this time by Colgate students, inventoried, studied … and then all of those objects were turned over to the Oneidas,” he said.

Unfortunately, the field methods course could not happen during the COVID-19 pandemic in Fall 2020, and Kerber has begun a phased retirement. He remains hopeful, however, that another professor will pick up where he left off with this important work.

“I’m hoping that my colleagues … could continue the offering of that course. … Having worked with [the Oneida] for almost 30 years, it seems that they’re very interested in their cultural heritage [and] they want to take measures to protect their history. And they want to pass on that knowledge to successive generations,” Kerber said.

President Brian W. Casey is also taking measures to involve Indigenous communities in plans for new construction on campus.

“We’re in good conversation with them, [the Haudenosaunee] — I want to keep them close, particularly as we restore the water and work on the landscape of the campus, I want to have them at the table,” Casey said.

These initiatives are immeasurably crucial for a positive Oneida-Colgate relationship, but much more can be done to help make amends. Dialogue regarding NAGPRA and other Indigenous struggles should be continued year-round on campus. A few thoughtful ways to get involved are by being conscious of the words you use, actively acknowledging that Colgate was built on Oneida land and learning more about Indigenous history and current struggles on your own or through lectures and events hosted by the university.

“Speak in the present tense when talking about Native and Indigenous peoples. We are still here. Just reach out, build relationships and most important of all — listen,” Lynch advised.

Ani Arzoumanian is a senior from Ridgewood, NJ concentrating in neuroscience with minors in creative writing and anthropology. She volunteers as a firefighter/EMT...