Art & Art History Lecture: Alison Alder

Visual artist Alison Alder was invited by the Art and Art History Department to participate in the Graphic Liberation series organized by Christian A. Johnson Endeavor Foundation Artist-In-Residence Josh Macphee on Wednesday, March 3. With screen-printed posters as her medium of choice, Alder has worked within community groups, art collectives, research institutions and Indigenous organizations with a focus on empowering communities through the visualization of common social aims.

Alder kicked off the discussion by showcasing some of her work for the virtual audience, explaining specific parts of each piece and for what they were advocating. Her newest project involves reprinting generations of feminist ephemera and annotating the documents to see how they are relevant to contemporary issues. It is an ongoing project that combines digital and screen prints, spread out as would be seen in a feminist meeting room.

Alder herself has done much to shift her field away from embedded androcentrism. In her time at Redback Graphix, she was determined to have a feminist impact on the culture of the organization itself as well as the art they made. She noted that the work became softer in some ways and broke away from the style of male artists which were very fluorescent. Now, on account of new exhibitions, feminist poster collectives and scholarship surrounding the production of women’s works, the unbalanced history of print-making is being redressed to elevate formerly glossed over artists.

Along with feminist projects, Alder steadfastly concentrates skill and effort into work with Indigenous people and issues surrounding mining and anti-nuclear activity.

“I liked her comment that she looked for and formed personal connections when working with varying activist groups, that the work needed to be meaningful to her to be effective,” Professor of Art and Art History Dewitt Godfrey says.

Alder discussed her journey towards deeper activism in which she commits herself to understand issues on the ground rather than blindly creating art for an organization without truly knowing its implications.

“When I started working at Redback Graphix I got a little bit uncomfortable for a while. I didn’t ever really want to be just like a hired gun for any left-wing organization that needed my graphics,” Adler said. “It was probably one of the more important pivots in my life, learning about that side of things in Australia and our history. It engendered an interest in me in how history is presented both through the media and literature but also graphically, and also how to put forward a statement that was mine built from knowledge rather than talking for other people. I wanted to talk from my heart rather than just presenting somebody else’s idea. That was a really big leap for me that I still try to ascribe to now.”

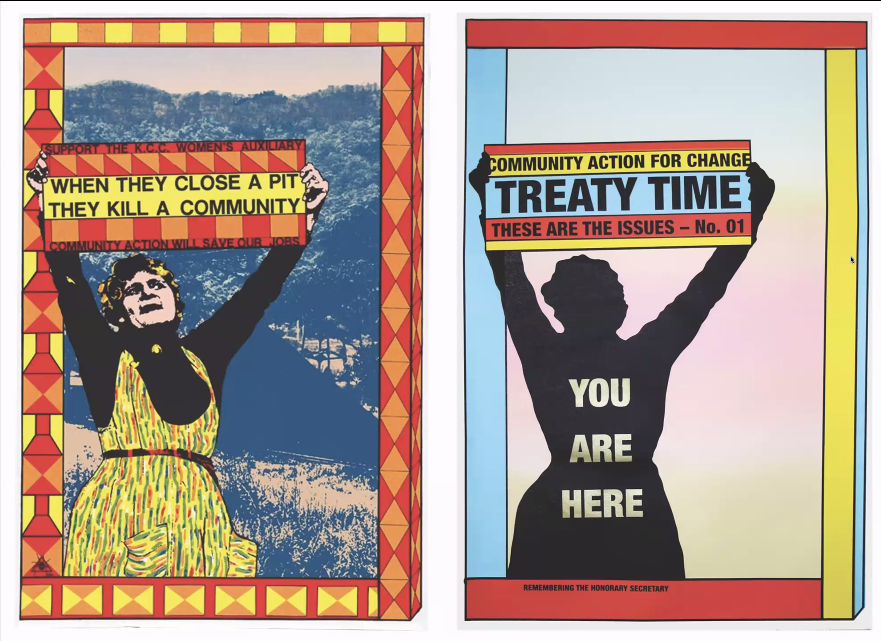

Alder and Macphee also discussed the afterlife of art, which sometimes grows new meanings in an unexpected context or even ceases to be relevant or helpful when new scientific information is discovered over time. Adler’s well-known “When they close a pit they kill a community” poster for the Miners’ Women’s Auxiliary is an example of the latter, which she has since updated with resolutions that are relevant to the present day while recalling the style and radical sentiment of the past campaign.

“I love that poster. I love the tactility of the dress, the patterning in the top and bottom, but I really am knocked out and blown away by the reimagining because one of the things about the original poster that is so striking to me now is that when I read it, I think about the reality of the fact that we know a lot more now than we did in 1980, of course. And right now we actually need to close the mines if we’re going to live on this planet. So it’s a really great and interesting example of how to navigate and negotiate how you make a very powerful image for something that you then realize eventually that you actually don’t want,” Macphee said.

Adler’s poignant and inspired art showcased in exhibitions and plastered in the streets continues to revolutionize the industry and provoke critical thought about the many ways to improve society and the environment.