Public Health Seminar Covers Inequalities in U.S Healthcare System

The Department of Global Public & Environmental Health and Pre-Health Pathways co-sponsored the spring 2023 public health seminar titled “Health Inequality: Patients, Providers, and the Experience of Care in the United States” on Feb. 7 in Case-Geyer Library.

Rebecca Upton, professor of global public and environmental health, delivered the event’s lecture, which she adapted from one she previously gave in 2020 when COVID-19 was the leading public health crisis. While the focus of last Tuesday’s lecture was different, much of the data Upton used was the same.

“What’s surprising, or maybe not surprising, is that a lot of these data have either not been updated and collected, in terms of national data on health disparities, or haven’t moved much since 2019. That’s really curious to me — because of the pandemic I suspect we need better data,” Upton said.

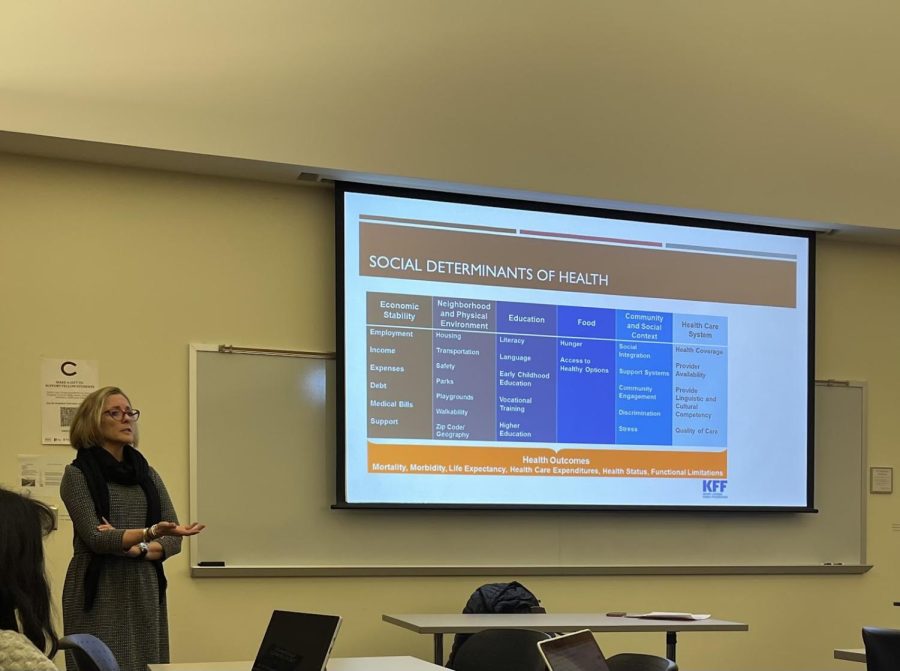

The lecture explored inequities in the U.S. healthcare system and their societal consequences. Health disparities — referring to when one group faces a higher burden of illness, disability or mortality than another — were the main topic of discussion. Upton highlighted disparities such as differences in insurance access and coverage, as well as the quality of care between different groups in the United States. Upton also touched on how COVID-19 was initially seen to be a “great equalizer” in terms of healthcare equality, which quickly proved not to be the case.

“I think in 2020 I talked a lot about COVID-19, and the rhetoric at the time had been ‘This is the great equalizer!’ And I mentioned this in several of my classes the other day. We were disabused of that notion pretty quickly, whether articulated or not, but it was clear that people who could afford to isolate somewhere — a rental home, for example — receive ventilator care or adequate access to medication, and later vaccines early on were likely to fare better,” Upton said.

While she began with COVID-19, Upton included a variety of statistics throughout her presentation that highlighted disparities within the types of healthcare different socioeconomic groups receive.

“Patients who are members of [person of color] populations do die at rates akin to those of white populations 30 years ago. That should trouble us,” Upton said

Taryn Lane, a first-year in attendance, said she found the race and mortality statistics to be the most shocking.

“The statistic that surprised me the most was that the gap in mortality between white and Black babies has actually widened since 1850. [That] means that there was less of a gap when slavery was still legal in some states,” Lane said.

Another topic Upton touched on was inequity within the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN). Amelia Seasholtz, a senior and board member of Pre-Health Pathways, was surprised to learn about the inequities within this system.

“I would have thought that the system for organ procurement and matching would not necessarily take race or ethnicity into account. However, as suggested by the data, there is racial prejudice within this system,” Seasholtz said.

Upton explained how OPTN data indicates hospital policies lead to inequity in organ transplants.

“Those in the white population have received 45.2% of all kidney transplants. […] African Americans have received only 27.2. Such a discrepancy is likely linked to, at the very least, a hospital’s determination of how much a patient can pay before receiving an expensive procedure. These policies are sometimes referred to as ‘green screens’ or ‘wallet biopsies,’” Upton said.

Another major health disparity Upton covered was the experience of Native Americans living on reservations. Due to the differences in a reservation’s environmental regulations compared to federal law, the military — as well as private companies — may use reservations to store weapons and nuclear waste which can pose major health risks to the communities living there.

“[This is] the disparity between what you’re dying of versus what you’re exposed to and not dying of,” Upton said.

She concluded her lecture by calling upon students to reflect on how healthcare is thought of in society.

“The real public health crisis might in fact continue to be racism and unequal access. Is this a human right, access to adequate health care? Is it a privilege we persist in calling a right? Should we just call it a privilege and own it? We’ve chosen the latter, but we don’t say that,” Upton said.

Student attendees responded well to the event, sharing that they would attend similar events in the future.

“I hope that Colgate has more events about public health in the future because I think knowing about the discrepancies in care among different social groups, as well as social determinants of health, is important for all students, no matter their major,” Lane said.

Emma McCartan is a sophomore from Guilford, CT majoring in international relations with a minor in Middle Eastern and Islamic studies. She has previously...