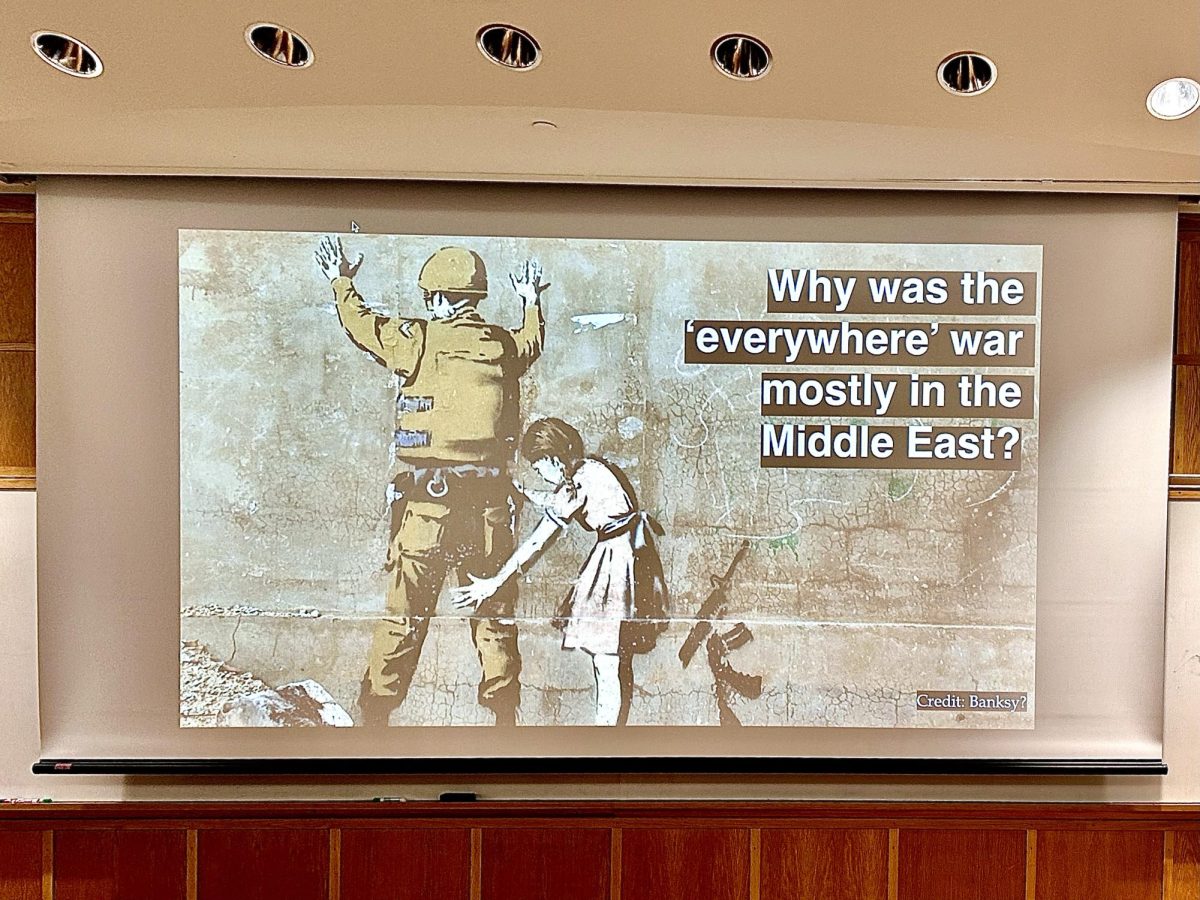

The Division of Social Sciences Spring 2024 Luncheon Seminar Series welcomed Colgate University faculty member Jacob Mundy on Thursday, Feb. 8. Mundy, who is an associate professor of peace and conflict studies and the director of the peace and conflict studies (PCON) program, provided insight into various conflicts in the Middle East — dubbed the “everywhere” war by professionals in the field.

The term “everywhere” war was coined by Derek Gregory in 2011 to describe the global war on terrorism from 2001 onward. Contrary to the wide-held belief that outside actors intervene in order to protect oil security in the Middle East, Mundy argued that the actual reality is closer to “oil for insecurity.”

Mundy is a Fulbright Scholar and has worked as a visiting fellow for the European Council of Foreign Relations. He has done extensive fieldwork in Tunisia, Libya, Algeria, Morocco and Western Sahara. Mundy is also the author of several books, including “Western Sahara: War, Nationalism and Conflict Irresolution.” His research has primarily focused on three case studies in Western Sahara, Algeria and Libya, respectively.

From his research in Libya, Mundy identified that economics was intricately tied to state development, state collapse, civil war and the motivations of outside actors. Libya is a notable exporter of oil and petroleum.

The concept of the “everywhere” war enforces that these sorts of instabilities are decentralized and not unique to places like Libya or the Middle East, where most oil exportation occurs.

“The global war on terror touches almost every nation in the world and has no central focus; [it] has no geographical emphasis in mind,” Mundy said.

However, Mundy claimed that the “everywhere” war is indeed a misnomer and that the war on terror is centralized. He cited statistics regarding military activity, terrorism, the refugee burden and covert operations to support his point — for example, that the Middle East was the site of two-thirds of global conflict-related fatalities from 2012 to 2016.

“So, why was the ‘everywhere’ war where it was? I think the statistics point towards a certain geographical concentration, a certain geographical bias […] in the greater Middle East,” Mundy said. “It’s not going to be a post 9/11 phenomenon; it’s going to be a much broader, 50-year story at least — if not much longer.”

A widely accepted explanation of this concentration is the familiar narrative of the supply and demand of oil, often called “oil for security,” which Mundy outlined.

“They have the oil; we need it. We have constructed economies that are highly dependent on petroleum as a primary energy source: everything from automobilization to suburbanization — you name it,” he said. “This comes with a kind of Malthusian twist. Oil is naturally scarce. That’s what makes it a strategic commodity.”

Once again, Mundy disagreed with this simplification.

“The problem with the narrative is, as any historian will tell you, that we can’t peg U.S. behaviors to a consistent policy throughout the Middle East,” Mundy said. “U.S. interventions and entanglements impede oil as much as they secure it.”

Alternatively, Mundy offers a counter-narrative of “oil for insecurity.”

“The underlying global economy of oil is that it’s not scarce, at least not in the natural sense. It’s actually the second most plentiful liquid on the planet,” Mundy said. “Oil is naturally bountiful, so if you’re going to try to get profit and power from it, you’re going to have to try to figure out ways to manufacture its scarcity.”

Conflicts in the Middle East have historically driven up oil prices, even those not typically associated with oil supply. These events are tied to increasing armaments and militarization, as well as social stratification. Conflict in the Middle East contributes to the profitability of arms and oil by artificially propagating oil scarcity. Disruptions of oil scarcity, such as the development of fracking, can likewise become an occasion for conflicts sustained through U.S. interventions.

One major downside of these cycles of conflict is the widespread de-development of the Middle East through war and the diversion of resources to militaries. Mundy even highlights how many unintended consequences feed into these cycles, from the proliferation of black markets to the destruction of tourism industries. Thus, oil insecurity plays an important role in the continued exploitation of the Middle East by outside actors.

Students in attendance noted that Mundy’s seminar provided important insight regarding current global issues. Sophomore Elizabeth Chin emphasized that the seminars are a powerful tool for learning about current affairs.

“I don’t keep up with current political issues as much as I wish I did. I feel like this shifted my perspective and provided more background about what is currently going on,” Chin said.

Junior Daniela Ortiz-Flores agreed with Chin and emphasized the value of observing world events through multiple lenses.

“I also am not very involved in politics. I don’t really watch the news because every time I do there’s always something wrong going on. So I’ve made the decision not to do that, although I like coming to talks like these,” Ortiz-Flores said. “I think it definitely helps to look deeper because there may seem like there’s an obvious answer, but in cases like this, there’s definitely so much more.”

Mundy’s talk summarized the causes and conjunctions of the “everywhere” war and proposed that conflict and the oil industry are closely intertwined by the need to make oil appear scarce. The next seminar in the Division of Social Sciences Spring 2024 Luncheon Seminar Series will be held on Feb. 22 with guest speaker Milica Kolarevic, who will discuss exploitation and bribery in “Corruption, Intimacy and Subjectivity: Being one with the clinic.”