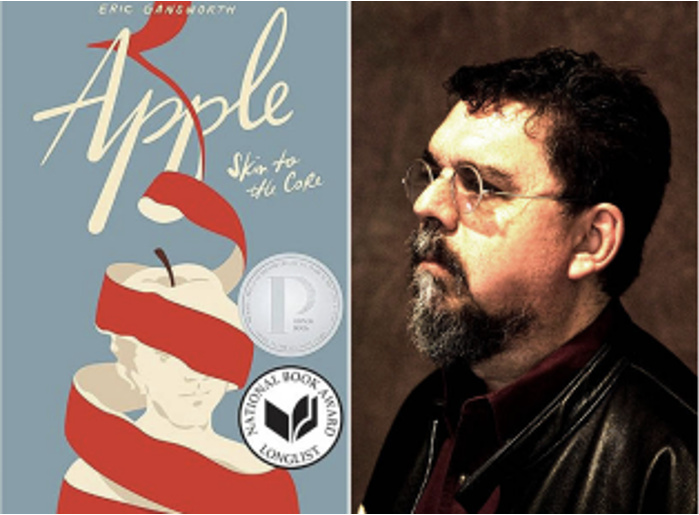

On Nov. 20, the Native American Studies program hosted a presentation by novelist and poet Eric Gansworth, Eel Clan, enrolled Onondaga. Gansworth, who was born and raised at the Tuscarora Nation, spoke to Colgate University students, faculty and wider community members about his illustrated memoir, “Apple: Skin to the Core.”

Gansworth, currently a professor of English and Lowery writer-in-residence at Canisius College in Buffalo, N.Y., was previously a NEH distinguished visiting professor at Colgate during the Fall 2016 semester. Gansworth was introduced by three distinguished members, past and present, of the Colgate faculty: Christopher Vecsey, the Harry Emerson Fosdick professor of the humanities and Native American studies in the religion department; Sarah Wider, professor of English emeritus; and Carol Ann Lorenz, associate professor of Native American studies emerita.

Gansworth’s presentation focused on his writing process and the inspiration behind his work. He began by sharing his role as a storyteller. Using wampum, which are strung together beads made of polished shells, he contextualized how some people are designated as interpreters of the stories shared by communities.

“In some ways, what I tend to like to do with my work is fight my initial urges. When I was much younger, I started to think that you should work on an idea only once […]. I’m not sure even at what point that changed for me, but to suddenly think there are many more ways you can approach the same idea and see a wide variety of elements, I think that turned out to also be true the more I understood wampum,” Gansworth said. “The people who are designated as readers are given the opportunity to emphasize the version of telling that wampum that they think is most important at that moment. In some very key ways, I kind of inadvertently wound up in that position of playing it out.”

He then discussed his entry into a the Public Theater’s Second Annual Native Theater Festival, an experience he credits as a microcosm of his career.

“The first play I had done was called ‘Re-Creation Story.’ And really, it came about as much as my career has, which is somewhat accidental. I’ve tried to work on very specific and targeted projects for many years, almost none of which have ever really worked out. And instead, something in my regular life intrudes and changes the way things happen,” Gansworth said.

Working in the theater also exposed Gansworth to the prejudice many Indigenous academics face. He shared that many are often called the derogatory term “apple” by fellow community members because they appear culturally disconnected from their Indigenous heritage.

“It is a reality of being somebody who works in the academy who is also Indigenous and in part because you simply cannot extricate yourself from the history of the boarding schools,” Gansworth said.

Gansworth accredits racial prejudice against Indigenous people in the academy and the arts with the previous existence of boarding schools. By attempting to immerse Native children in Euro-American culture, they consequently erased Native culture.

“The boarding school’s job […] was literally to kill the Indian but save the man. It was to bring children into an environment in which they lost all connection to their community identity and to also immerse them into American culture at the time. And to also keep them a specific number of years, so that if they were to go home, they would no longer be a fit,” Gansworth said.

Gansworth’s memoir is an exploration of how the narratives of his relatives were shaped by outside forces and how his experiences as an Indigenous man have been shaped by the society in which he lives. Two of Gansworth’s grandparents went to the former Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pa. He shared that their history is largely lost because his family felt it was too taboo to discuss and his grandparents had passed away before he could speak to them about their experiences. Gansworth discovered a photo of his maternal grandmother during his research for his memoir and felt compelled to learn more about her. He discovered that in the 1940s, an ethnographer came to the reservation and stayed with her who then recorded conversational Tuscarora. The memoir explores his familial history.

Gansworth concluded by sharing what he thinks the significance of his memoir is.

“By calling [the book] memoir, you kind of change the landscape for the reader because they understand it’s your version of the truth,” Gansworth said.

He explained the conversation he had with his family before the release of the memoir on the importance of it.

“I said, ‘I just want to be clear that you understand what a memoir is and what it means. It is more exposing, but it is also not for you, it’s for the generations of our family that come after us. Because we’re not going to be here, at some point, and whatever we’ve got here, they’re going to have, and we know that people did it for us. What we have left of these photos from our grandparents and from our parents, that’s because somebody else was being responsible in the same way that wampum requires the responsibility of someone to remember the story,’” Gansworth said.

First-year Daniyar Ali, who attended the lecture for his CORE Haudenosaunee class, found the presentation to be an important extension of what he had been learning.

“I was at the presentation for my Haudenosaunee class, so I have learned a lot about their culture through that, but through his talk, I learned a lot more about more contemporary culture and issues they were facing,” Ali said. “For example, everything he said about the boarding schools was pretty much new to me, and I found it surprising to hear about. I also appreciated him talking about his experience both as a multimedia artist and as a Haudenosaunee in the arts industry.”

Junior Tabitha Saour attended the lecture for her global Indigenous history class and shared her thoughts on the presentation.

“I thought the presentation was very interesting, and I really appreciated how much of the presentation was told through story,” Saour said. “I have not read the book yet, although I want to, especially after hearing Gansworth read some of the poems from it.”