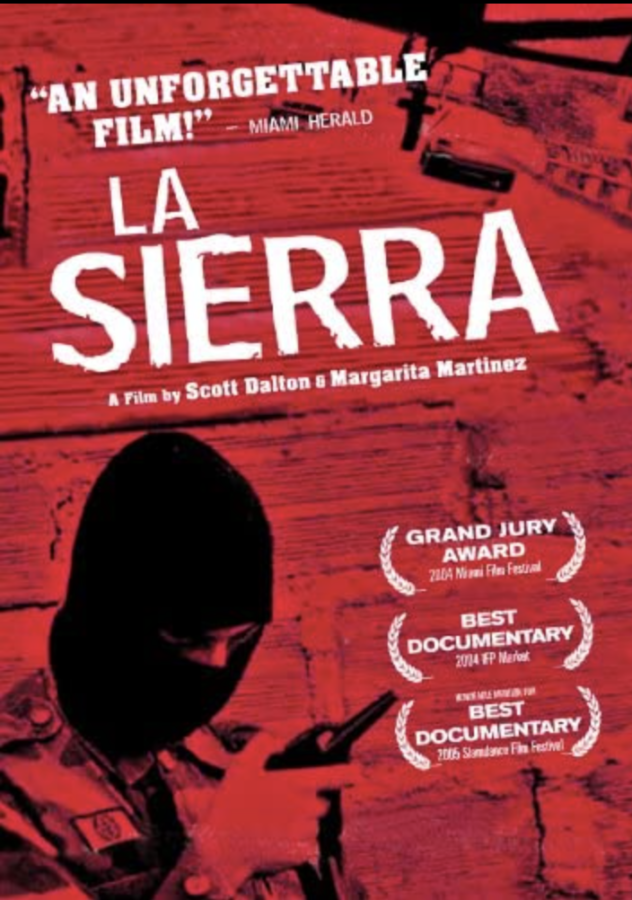

Margarita Martinez: “La Sierra: The Daily Life of War in the Colombian Barrio”

Margarita Martinez, a Colombian journalist and documentary filmmaker, gave a lecture on her 2018 breakout film, “La Sierra: The Daily Life of War in the Colombian Barrio” on Wednesday, March 24. Martinez, who received her master’s degrees in International and Public Affairs and journalism from Columbia University, worked as a journalist for NBC in New York until becoming a war correspondent for the Associated Press out of Colombia, South America.

This film followed the lives of young Colombians living in Medellín who lived in the area controlled by gangs and tied to the national paramilitary forces. Martinez and her colleague gained access to the neighborhood through her war correspondent connections in the paramilitary, as well as by the willingness of the people in the neighborhood to talk to the press. Martinez noted that the paramilitary leaders did not fully comprehend that she and her colleague intended to stay for a long period of time, which is another reason they gained access.

Following her story of access, Martinez commented that there were no issues with paramilitary influence on her film because, unfortunately, the majority of people she interacted with died before the end of filming. This was an incredibly brutal time in Colombia and the sheer number of young men who died was unbelievable.

Many of these young men and women in the neighborhood were born into the violence and were the second generation of the war. Many had already lost fathers or other relatives to the war.

During the lecture, Martinez was asked how she dealt with the fact the people she interviewed were kids. Many of the people she focused on were women which was not an intentional choice; rather, it was a result of many of their husbands, sons or brothers dying. Martinez did say it was an incredibly hard time for the young women as well because after their families died, they had great difficulty finding jobs to support their children.

As a follow up to where her documentary subjects are now, Martinez told a compelling story of one of the young gang members who ended up going to prison. However, prison saved his life. All the other gang members were killed and being locked up was the only hope for him to survive.

One question that was brought up was if the filmmaking brought unwanted attention to the neighborhood or the paramilitary presence. Martinez said that the military was fully aware that the gangs existed in this community, so being onsite filming did not draw any special attention to that gang presence. She also commented that after being there for a significant amount of time, she and her colleague became part of the family of the neighborhood, so they drew no additional attention.

It helped that they only had one camera as well. Martinez said that was a conscious choice because it allows the film to be more intimate, but at the same time they had no budget for the film and were paying for it themselves, creating limitations on gear.

One final question asked of Martinez was if she ever felt they were not going to be able to finish the film. “All the time,” she said. The leadership and power among the gangs and paramilitary were constantly shifting which created uncertainty for the film and what they needed to be covering. Martinez explained that they just wanted to work to humanize urban gangs and felt that what they were doing would achieve that goal, despite the shifting political environment around them.