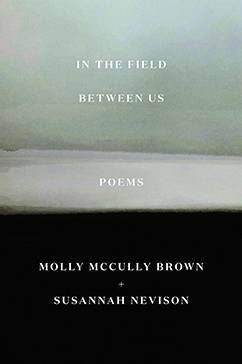

Susannah Nevison and Molly McCully Brown Discuss Their Book of Poetry, “In The Field Between Us”

“IN THE FIELD BETWEEN US”: McCully Brown and Nevison’s poetry collection explores disability and friendship through the epistolary form.

On Nov. 4, Colgate University hosted authors Molly McCully Brown and Susannah Nevison as part of the Living Writers Series. The two women worked together to create a new paradigm for the poet in their epistolary poetry collection, “In The Field Between Us.”

McCully Brown has also authored an essay collection entitled “Places I’ve Taken My Body,” as well as “The Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded,” a poetry collection that received the Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize and was included in New York Times’ list of notable books.

Nevison is the author of two poetry collections, “Lethal Theater,” which won the Charles B. Wheeler Poetry Prize, and “Teratology,” which also won the Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize.

In their shared body of work, poetry is treated as a dialogue rather than a monologue, and the poet herself a corporeal friend. Traversing the dangerous territory of bodies and dreams, the poets write of dreams about bodies, and the contrariwise bodies of dreams.

What’s more, the collection is formatted as a series of letters between the two authors over the course of multiple months. Well, letters communicated via email.

“It is 2021,” Nevison quipped.

The two write about their experiences with disability, its terrors and its beauties in all their surreal glory. In a world not built for disabled bodies, they seem to have created their own shared universe, wherein the boundary between dream and reality is blurred, and the darkened landscape is ripe with possibility.

The whole collection gives the feeling of listening in on a pair of brilliant friends, whose intimacies you may not entirely understand, but can appreciate from a distance.

“There’s something delicious and transgressive about reading epistolary poems,” Associate Professor of English Jennifer Brice said in her introduction to the work, “You’re feigning interest in the newspaper while secretly eavesdropping on two brilliant, luminous young women conversing in a language they seem to have invented but that somehow, you can understand … or at least, you think you can.”

In person as in their poetry, McCully Brown and Nevison fill in each other’s gaps. They often defer to one another in responding to questions, and occasionally share sly, personal looks with one another as if referencing some inside joke to which the audience is not entirely privy.

“You skipped a page,” McCully Brown pointed out to Nevison early into the reading, half-hiding a laugh.

“Oh my Jesus Christ!” Nevison responded, before dramatically flipping the page back. “Okay, now I’m only gonna turn one page.”

The two women speak as they write – with a biting intelligence and wit that takes a minute to process.

“We invite you to join us on this weird adventure,” Nevison declared in her introduction of the work.

The “weird adventure,” which is somehow simultaneously personal and universal, private and public, is one that draws in even the least poetically-inclined readers.

“I don’t usually read poetry,” Colgate first-year Ben Coddington said, “but I found the epistolary style to be an interesting and unique format different from what little poetry I have read before.”

Nevison and McCully Brown’s lyricism is refreshing and familiar, but also powerful in its discomfort. Like all good art, it provokes deep, necessary thought.

“Reading those strange and luminous poems forces those of us who move through the world more easily, without pain, to slow down and listen with curiosity, without judgment,” Brice said, “I’m reminded that simply paying attention to the ways the world comes at someone else — someone very different from you — can sometimes be an act of radical empathy.”

Disability, in Nevison and McCully Brown’s work, is not something to be hidden or tiptoed around. Able-bodied readers are forced to look their privilege in the eye, and, perhaps even more importantly, understand that they may never understand.

“Dear M,” Nevison writes, “The dream where I’m legless/ isn’t a nightmare, and I’m not/ afraid — there’s light and a river/ and everything is exactly/ how I’d hoped.

“Dear S,” comes McCully Brown’s response, “Look, there, our dead/and heavy elements/are piled high beside/the silhouette of what/we were before.”