University Understaffed as Pandemic Effects Remain

It has been one month since students returned to campus and the 2022-2023 school year is in full swing, but many University offices are having trouble keeping up due to a campus-wide staff shortage.

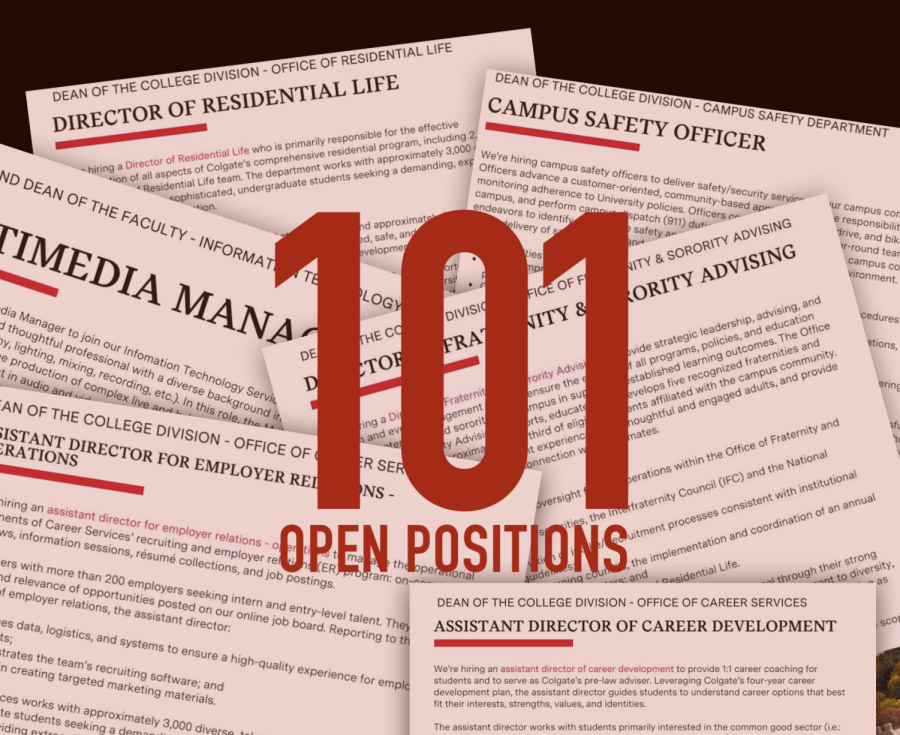

As of Tuesday, Sept. 20, Colgate’s career opportunities website had 101 postings. Since one posting may represent multiple openings, the real number of vacant positions is even higher, Director of Talent Acquisition and Development Cherie Ball said. She told The Maroon-News that this level of understaffing is far from normal.

“We might have had the same number over a longer period of time, but they haven’t been at the same time,” she said. “We haven’t had 100 openings all in one period.”

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Human Resources could expect to receive as many as 40 applications for a position — now, according to Ball, they might only get two. Recruiting and hiring a new candidate for one position used to take about 45 days. The current timeline can be anywhere from six to eight months.

The University is not alone in experiencing staffing difficulties.

“What’s interesting is that we’re just fighting the same structural issues that the whole country is,” President Brian Casey said. “There are universities that have asked all of their faculty and staff to volunteer to staff the cafeterias because they cannot staff their dining halls — we are not going to do that.”

When the pandemic began, Colgate halted the ten-or-so ongoing searches for financial reasons, according to Ball. But, as campus life approached a “new normal,” these delayed opportunities were reopened alongside new positions.

“That’s when we started to realize, one, we’ve got all of these openings, but two, our candidate pools are no longer looking the way that they did prior to the pandemic,” Ball said. “Towards the Fall of 2021 was the largest year [for vacancies], and now we can’t catch up. We can’t get positions filled fast enough because we don’t have applicants in the pipeline to get those filled.”

The pandemic changed where, how and when people worked. In what was dubbed the “Great Resignation,” millions of people quit their jobs after the pandemic and remote work began. But more generally, there has been a shift in how professionals think about work.

“I don’t see Colgate as being out of the norm nationally for what appears to be a demographic change in the nature of labor,” Vice President for Administration Christopher Wells said.

Ball elaborated on this change, explaining how professionals now have different priorities when it comes to a job search.

“They quit their jobs. Now when they’re looking at jobs they aren’t necessarily looking for the things that we traditionally expect people to look for like salary, title or career advancement,” she said. “They’re looking more for work-life balance, work that is meaningful to them, work that provides opportunities for them to maybe spend more time with family, working from home.”

Wells also described how the increase in remote work opportunities reduced the University’s local standing as an employer. As remote jobs became more common, professionals could expand their jobs search nationwide. For example, he said, working remotely could allow an IT specialist in Hamilton to earn New York City wages without paying New York City rents.

“There was a time when for as far as you could see or drive in 20 minutes, Colgate was the best employer available,” Wells said. “Our competitive advantage there was degraded over the course of the pandemic.”

According to Ball, the University lost possible candidates because its pay rates were not competitive enough, further shrinking an already small applicant pool.

In response, the University invested something in the area of $650,000, Wells said, to increase the pay scale for employees earning an hourly wage.

“If there are fewer workers to go around, the people who will get them will be the people who are paying the most,” Wells said. “To remain competitive, particularly for entry-level positions, we had to put more money into our compensation.”

This is not the only action Colgate and its Human Resources department have taken in an effort to fill vacancies. Ball listed many initiatives, including encouraging internal promotions, broadening position qualifications, hiring interim staff, leveraging social media outreach, attending job fairs, increasing work hours and location flexibility and promoting wellbeing.

Still, Ball said the desperate need to fill vacant positions will not come at the price of candidate quality.

“It’s still important for us to make sure that we are trying to broaden our pools and diversify our pools, so we’re doing our due diligence and taking the time to hire good quality candidates versus just getting bodies in seats,” she said.

Human Resources itself is understaffed. Ball and her team are hoping to hire an additional member of its recruiting team to help fill positions.

“Part of the challenge is we’ve got two of us currently,” Ball said. “We’ve got all of these openings and you can only get to so much, and so we’re not as responsive as we want to be in being able to help searches move more quickly…the capacity isn’t there.”

Career Services, Advancement, the Office of Residential Life and Information Technology Services are some of the campus offices with the most “critical” need for additional staff.

“Those are the areas that we consider to be critical because they have one, such a large number of vacancies and two, a lot of those are student-facing,” Ball said. “Obviously our students are the most important asset here and so we want to make sure that students have the right experience and a lot of those vacancies could potentially impact the experience they have.”

The personnel shortage is limited to University staff, Wells said, noting that faculty and academic departments have not experienced the same issue.

“The heart of the student experience here is our faculty and that’s a whole different ball of wax,” he said. “We have not had a difficult time recruiting faculty to the campus, our faculty remains world-class.”

But, students are still feeling the effects of an understaffed campus.

Senior Gilly Orben hoped to make a follow-up appointment with Career Services staff after meeting with them on Sept. 7. She said she was told she would have an appointment every two weeks, but the soonest possible availability was in mid-October.

“I couldn’t schedule my next appointment until over a month later,” Orben said. “It was like four-and-a-half weeks later because they didn’t have enough staff members, and they didn’t have enough slots for appointments.”

Orben is graduating at the end of this semester, meaning her job-search timeline is beginning much earlier than many other seniors.

“It was definitely very frustrating because since I’m graduating early, I’m in the middle right now of trying to apply for jobs because it’s a bit earlier than other people would,” Orben said. “So like it’s really frustrating because I want my resume to be complete and looked over before I start applying for jobs, and it delays that process by like three weeks. So it definitely makes me feel not prepared.”

After losing members of its staff this year, Career Services currently has four vacant positions for which it’s looking to hire full-time staff.

“Higher education is a field that naturally experiences a good amount of turnover. However, this spring and summer, several colleagues transitioned out of their roles,” Teresa Olsen, Assistant Vice President for Career Initiatives, told The Maroon-News in an email. “We have successfully hired a few new, talented teammates, but some of our hiring processes are ongoing.”

Even after adding the maximum number of appointment times to current advisors’ schedules, Olsen said Career Services is still dealing with wait times for appointments.

“On the whole, students have been gracious about our scheduling,” she said. “I think they appreciate how hard our team is working to try to be helpful. But we understand that everyone will be in a better place when we return to being fully staffed.”

Both Ball and Wells agree that things are looking up.

Larger pools of quality applicants are building at an increased rate, according to Ball, and University administration is optimistic that they will get filled.

“I do think we’ve turned the corner and we’re now rapidly getting to a place where we’re really addressing vacancies in a way that’s more like the old normal,” Wells said.

Josie Rozzelle is a senior from San Francisco, CA concentrating in political science with a minor in French. She has previously served as multimedia manager,...